Cut Out for It

Cut Out for It

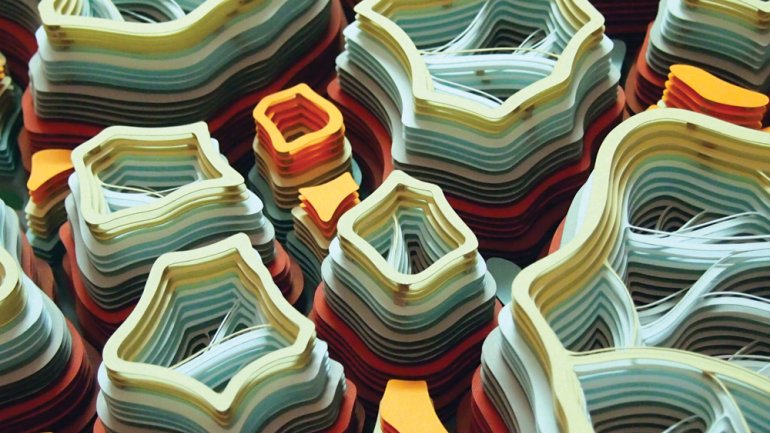

Charles Clary takes scrapbook paper to dazzling new heights.

Charles Clary laughs when he reveals the name of his art supply store – the Sassy Scrapper.

“It does feel a little weird to go to a scrapbook store to get my paper,” says Clary, 34, who lives in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. “My fiancée jokes that I’m always the only dude in there. Sometimes they’re having a class, like on how to make a flower, and I’m there buying 400 sheets of paper.”

From the 200-plus colors he has to choose from, Clary typically selects bright, bold tones to create the sophisticated, amoeba-like forms he makes by layering piece after piece of paper. When fully stacked, they resemble millefiori patterns so precisely rendered it’s hard to imagine each is cut by hand.

Clary’s past informs his designs. As a boy in eastern Tennessee, he devoured comic books and watched cartoons, attracted to the bold colors and fantastical shapes that he would replicate. “My mother would be at her table drawing and I’d be on the floor drawing,” he says. “She always encouraged me, whatever I was working on.” Later, science classes introduced him to life under the microscope.

“Way back when, I wanted to be a microbiologist, and I’m still fascinated with fungus, bacteria, viruses,” he says.

In graduate school at Savannah College of Art and Design, Clary instilled those properties in his artwork, making what he describes as “weird flat paintings based on graffiti but with elements of Dr. Seuss.” As his work progressed, he created organically shaped platforms that he’d cover with cut-out drawings in neon green and pink.

During an internship at a Brooklyn gallery in 2007, a chance walk past a paper shop changed his direction.

“It just came to me that I could cut out shapes from the paper instead of cutting out what I’d painted. I walked out of there with as much paper as I could carry and started playing around. I felt like I’d found something I could really push the boundaries of, and it wasn’t anything I’d seen before.”

Clary deemed his early work finished after four layers. Now he’s up to a mind-boggling 20 to 45 apiece, so vertical that he calls them “towers.” To achieve his trademark look, he traces out designs with a pencil and then slices into each layer with an X-Acto knife, replacing blades as quickly as a racing pit crew changes tires. He approaches the physical rigors with the mentality of an athlete.

“Early on I figured out what was comfortable for me in the long haul and to manage my time. There are weeks I’ll work 80 hours on various projects. I cut a lot using the force of my elbow or shoulder instead of a short stroke with my wrist, and I can use my pinkie as a brace.”

The art world has embraced Clary’s work, which he sometimes displays on a wall as part of an installation or embeds in wall-mounted boxes he builds. He’s represented by four galleries, has a two-person show at New York’s Nancy Margolis Gallery to his credit, and has been spotlighted in several publications and books.

“It’s been super-humbling for me and also beneficial for my students to see a working artist,” says Clary, who teaches four art classes a semester at Middle Tennessee State University, where he earned an undergraduate degree in painting.

The artist’s only setback has been a personal one – losing his parents to cancer within two weeks of each other in 2013. As a way to cope, he created an installation of 204 pieces, representing the days between his mother’s diagnosis and her death.

“I stopped making work for a couple months, but later it became something I could turn to and get some semblance of happiness,” he says.

In his latest work, Clary is drastically altering the boxes he places his pieces in. “I hit on this idea of using drywall. I’ll make a pretty nice square of color, then beat the heck out of it with a hammer, so it looks like something violent has occurred, and within that opening I’ll put in a paper sculpture. It’s like a beautiful disaster. I’m super-excited. It’s that kind of energy I had when I first found paper as a medium.”

Diane Daniel is a writer in Durham, North Carolina.