Does Craft Bring Us Closer To Nature?

Does Craft Bring Us Closer To Nature?

Q: Over the past 50 years, technology has grown ever more pervasive. People are arguably less and less connected with nature. Can craft somehow reconnect them?

A: I know the feeling. It comes upon me when riding a train, as I watch the landscape scroll past like a beautiful but dull film. Or when I stare mesmerized at a computer screensaver, with its lazily zooming images of lush jungle or sun-splashed beach, or watch the latest nature documentary – the sex lives of spiders in extreme closeup. In all these cases, nature is presented in an accessible form, laid out for delight and appreciation. But because appreciation is offered via the mediation of technology, somehow nature feels more distant than ever.

Rather than actual separation from the landscape – after all, any American with a bus ticket can see plenty of trees – I think it is the commonplace encounter with “canned” nature that makes us feel disconnected. So much so that, even when we do make it to the waterfall, we may be reminded of a shampoo ad, an association that may well spark resentment. We wouldn’t want to do without our trains, computers, and televisions. But we hate them for filtering our experience.

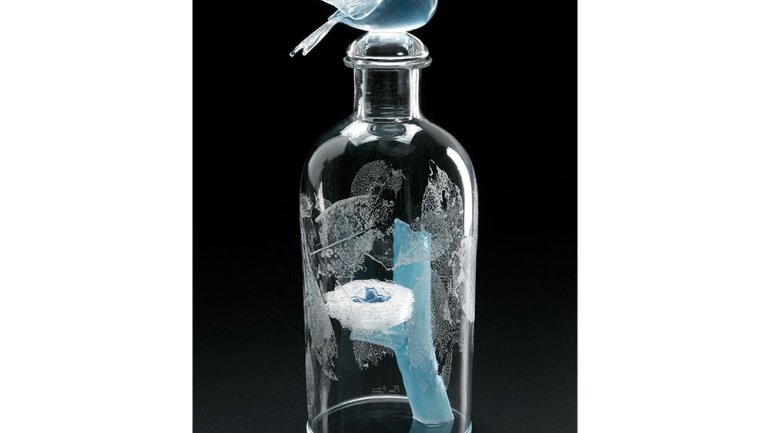

Craft offers itself as a ready remedy to this dilemma. Other technologies give us nature in optimized form, as lush and fake as a tree in Disney World. Craft, by contrast, brings us face-to-face with nature’s obstinacy. Sticky clay, splintery wood, sagging hot glass: These are the difficult materials in which makers must somehow realize their intentions. On screen, nature comes attractively packaged, its resistances all ironed out. A handmade object condenses nature, too, but in a different way. It speaks the truer, richer language of intractable substance.

This said, it is worth noting that the word “artificial” used to mean simply “made by hand.” Human skill was viewed in opposition to organic processes. That distinction was enshrined in the cabinets of curiosities of the 17th century, which were typically divided into artificialia and naturalia. In this context, as in most places and times, craft was valued for its marvelous ability to overcome nature, not just reshape it.

You can certainly find craft that explicitly celebrates nature, displaying its inherent glories; George Nakashima’s tables made from cross sections of trees are a good example. But this sort of work is a tiny slice of what craftspeople do. In part, that’s because so-called “raw” materials come to most makers in a highly processed form.

Few professionals have the time or opportunity to dig and refine their own pigments, spin their own fibers, or season their own timber. And anyway, it’s more difficult (and therefore more interesting) to radically transform nature than to leave it in its pure, unaltered state. This is as true in today’s digitally enabled age as it was in the Renaissance.

So does craft reconnect us to nature? Perhaps, but in most cases only indirectly, by way of human ingenuity. In this respect, it’s not so different from other forms of technology after all.

Glenn Adamson is head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and co-editor of the Journal of Modern Craft.