An Intimate Knowledge

An Intimate Knowledge

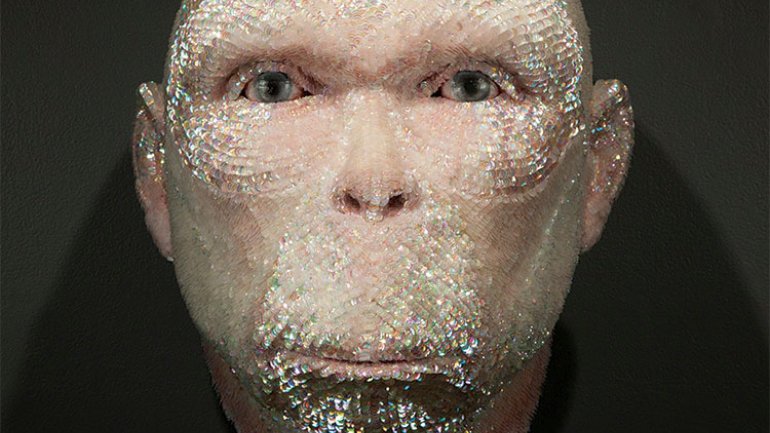

The surfaces of Lindsay Pichaske’s creatures undulate with unusual materials. Swirling sunflower seeds form a nubby elephant hide; tens of thousands of pearlescent sequins glisten on a primate’s face.

These artificial, even alien skins should, by a certain natural logic, render Pichaske’s sculptures strange, fantastical – mark them as not of this world. The surprise is that these lovingly applied surfaces lend the artist’s work an intoxicating familiarity; they draw you in, pull you closer. And before you know it, these creatures, with their carefully sculpted faces and gleaming eyes, feel real.

Pichaske, 32, began experimenting with surfaces in graduate school at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she earned her MFA in ceramics. She’d visited the cadaver lab – “just one or two times,” she clarifies with a small laugh. “I was drawn to the way that they would peel back the skin – not to get too morbid – and the muscle striations were the most gorgeous patterns.” After one visit, she returned to her studio, where she had a few potato-like sculptures sitting around, experiments in how basic a form she could make that still had some kind of life-like presence. She began wrapping one in pink embroidery floss, recreating musculature.

“It just came to life,” she recalls. “There was something about those stripes and the string, and just holding it in my hand and wrapping. I just loved the act of doing it.”

Her work today, of course, has grown into a far more complex undertaking. Darwin’s Muse (2012) is a 2-foot head based on a great ape, his pale skin made luminous with 26,190 sequins. Pichaske created him – meet the primate’s level gaze, and it’s impossible to remember he’s technically an “it,” an object – during a residency at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts. She was standing on cinder blocks, painstakingly applying sequins and adhesive, her neck aching from the weight of a heavy respirator, when a visitor walked past, surveyed the scene, and asked the perhaps obvious question: Why?

“I realized it was almost like when you’re braiding someone’s hair – or brushing an animal’s fur,” says Pichaske, who is now based in Mount Rainier, Maryland, near Washington, DC. “You discover new parts of their body that you wouldn’t otherwise know about.” In covering her creations with hyper-detailed skins, Pichaske pulls in her viewers, invites them to participate in an intimate knowledge. “It’s wanting people to look all the way around an object. Behind an ear; the hidden parts. You discover a little bit more about the creature that way.”

Pichaske’s connection with her creatures begins in the sculpting process. Lately, she says, she’s been starting with maquettes, an inch or two in scale. “It’s almost like a poem or a brainstorm before I start.” With a rough idea of color, covering, and form, she often allows the exact species to evolve along the way; sometimes the result blends two or more. That said, she notes, she’s always been interested in great apes and other primates. Growing up, “I wanted to be Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall,” Pichaske says. As an undergraduate, she came within one class of a biology major – but ultimately chose art.

It was a junior-year class in figure sculpting in Italy that got her hooked on clay, she says: the way the malleable material mimics body and flesh, how handling it is as much about feeling as seeing.

She spends the most time sculpting faces and hands. “It’s when the piece comes to life,” she explains. They’re also the parts that will remain uncovered – emotive hotspots. It’s not entirely surprising to learn that, post undergrad, Pichaske took a concentration in figure sculpting at Penland School of Crafts with Cristina Córdova [“The Body Eloquent,” Feb./Mar. 2012], or that she worked as Córdova’s assistant from 2007 to 2008. “It was huge,” Pichaske says. “Learning how to articulate gesture and elicit emotion through this material with her – and then actually working for her, learning how to be an artist.”

In July, Pichaske, who is a 2013 NCECA Emerging Artist, had her first solo show at Foster/White Gallery in Seattle. She showed eight pieces, including some of her newest work such as a giant aurochs head, lying on its side and coated in black sand, and a Japanese snow monkey, covered in silky, translucent monofilament.

“Materials give the figure its identity,” Pichaske says. She’ll often spend weeks searching for ones that match the idea she had in mind at the maquette stage, experimenting with them to see what patterns and “rules” they make for themselves in use.

“They have to undergo some sort of transformation in order for me to fall in love with them,” she says. “The way sequins can turn into scales or the way sticks can become fur.”

The way a sculpture can become a being.

Julie K. Hanus is American Craft’s senior editor.