An Intricate Language

An Intricate Language

Forced to abandon oil paints, Nebiur Arellano found her style on silk.

Deep in the heart of the Andes Mountains, and even in apartment basements in urban Peru, archeologists are still discovering Incan burial sites. Each time Nebiur Arellano spots a news report about excavations of a tomb that an ancient ruler thought was his final resting place, her heart palpitates just a bit, and she dives in to read about the treasures uncovered inside. A sociologist turned artist, Arellano paints elaborate patterns on stretched silk, often evoking the bold red, blue, and metallic motifs of Andean textiles and pre-Columbian art.

But this wasn’t always her artistic vision. For the first 10 years of her career, Arellano, a Peruvian native, painted more abstract works in oil on canvas and wood. She was reluctant to give up the medium, but when health concerns prompted her to make a switch, her works became more intricate and more connected to her cultural heritage. They also resemble works by a famous Austrian artist, purely by coincidence.

“When I show my work, so many people say, ‘Oh, it’s Klimt!’ ” Arellano says. “Of course, I like Klimt, but I have to explain my inspiration.”

When she shows her work to people of Peruvian heritage, or to people who have a background in South American art, she gets a different response – one of recognition and satisfaction. “Pre-Columbian art (and food) are something that Peruvians are very proud of,” she says.

Whether at art shows or working in her home studio, Arellano always keeps books of Incan art and Peruvian textiles close at hand. Deep crimson-dyed llama and alpaca wools dominate many of the preserved patterns. “The designs are so colorful, geometric, and very modern,” she says. “It’s like a language, with tiny little designs.” Among the artifacts that have inspired her most are those found in the tomb of an ancient ruler known as the Lord of Sipán, whose grave was unearthed in 1987. “The golden breastplate with turquoise is splendorous,” she says, waving her hand over a photo from a museum exhibition.

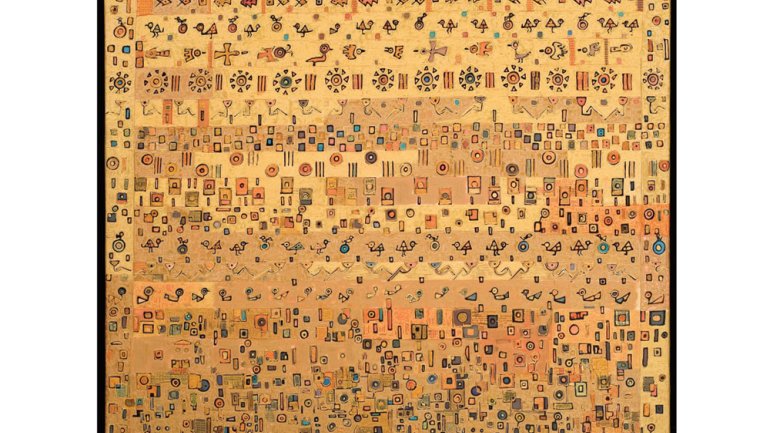

Whether or not people recognize the cultural foundation of Arellano’s work, few can discern her process by looking at a finished painting. She be-gins by stretching silk – raw, crêpe de chine, or organza, depending on how much texture she wants – “really tight” over a frame. Before painting the silk a base color, she outlines her grand-scheme design with thin trails of black gutta resin-based paint. One painting might have hundreds of shapes – rectangles, circles, crescents, and the occasional whimsical petroglyph. After the base dye has dried, she goes back over some of the shapes with accent colors, and fills in many with tiny metallic lines, like filigree. Once hung on a wall, the silken shapes left unpainted shimmer, like bits of mirror in a golden mosaic.

Arellano’s works hang in galleries from Lima to Geneva, and she’s enjoyed solo shows in France and Germany, as well as her adopted hometown of Bethesda, Maryland, just north of Washington, DC. It can take four days for one layer of paint to dry, and up to a month before Arellano deems a work complete; she now works mostly on commission but also does gallery shows. Her pieces sell for up to $12,000 – not bad for someone who wasn’t sure she should become an artist. Fortunately, her husband encouraged her to follow her passion and attend art school rather than grad school. She took painting classes first in Lima and then at the Corcoran School of Art after they moved to Washington for his job at the Organization of American States in 1998. At the time, she was experimenting with silk, watercolors, and other mediums, but still often painted with oils. But from her earliest days as a painter, she wondered if fumes from the paints were one of the triggers for the migraines she suffered since her early 20s. Finally, a doctor recommended that she stop, and around 2000 she reluctantly packed up her oils and made a permanent switch to water-based paints.

The headaches subsided. Grateful for a second chance at art, Arellano began to approach her health more holistically and made changes to her diet and exercise routines. Painting on silk, she says, “has taken my art to another place, to create my own technique [that] maybe I wouldn’t have gotten if I had just kept painting oil on canvas.”

Now 58, she still faces physical challenges. Not long after she switched to painting on silk, she was diagnosed with chronic tendinitis in her shoulders, a casualty of too many hours hunched over her silks, painting thin lines and metallic details. When she is experiencing a lot of pain, she ponders ways to make her work less intricate. “But the intricacy of my paintings is what I am as an artist,” she says. “I can’t fight with it.”

So she makes do, stretching, going to physical therapy and taking frequent breaks, sometimes dancing to the world music she plays in her studio.

“I just have to be mindful and look after my health. It’s part of life, and what you chose as your passion,” she says. “As artists, our bodies are our instruments. We have to take care of them.”

Nebiur Arellano will show her work at the American Craft Council Baltimore retail show Feb. 20 – 22. Rebecca J. Ritzel is a writer in Alexandria, Virginia.