Legacy of Mastery

Legacy of Mastery

NY / New York City

What Would Mrs. Webb Do? A Founder’s Vision

Museum of Arts and Design

to Feb. 8

Aileen Osborn Webb (1892 –1979) was born to wealth and married into more, but was never one to sit around polishing her pearls. This influential woman harnessed her resources and connections to serve others, founding what would become the American Craft Council, the Museum of Arts and Design, and more. That legacy is the focus of "What Would Mrs. Webb Do? A Founder's Vision," which opens today at MAD. Curator Jeannine Falino fills us in about the show. An excerpt of this Q&A ran in the Oct./Nov. issue of American Craft.

How on earth did one woman accomplish so much?

Aileen Osborn Webb was a woman of privilege with a social conscience – her father was president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a signifier of great wealth – but he was also a progressive who was president of the Children’s Aid Society in New York for fifty years. His dedication to the needy must have affected her thinking. She was also involved in Democratic politics in the 1920s and was deeply impressed when she first met Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Webb also had a natural ability for what we now call strategic planning: with a single-minded purpose, and over the course of some fifty years, she established organizations that supported different aspects of the craftsman’s life, whether it was professionalization, publication, education, exhibition, or sales. We owe a great deal to her.

How did she become involved with craft?

The story that I love best concerns Mrs. Webb’s early involvement in Putnam County Products in Garrison, New York, her first craftsman’s salesroom, around 1929, during the Great Depression. She was hoping to alleviate poverty among people who wanted honest work and could find none. She invited people in Putnam County, north of Manhattan where she lived, to bring in goods for sale. But she didn’t bargain on getting crafts. As she recalled, “I thought of it more as string beans and eggs, but actually within two months it was things which people made by hand.” The quality of materials that poured in convinced her that she could help these people make a living with their talents. To me, this moment represents Webb’s moment of recognition – her epiphany, as it were – that there were talented Americans who merely needed the proper outlet for their goods. From that modest beginning, she formulated a plan and by 1939 had convened a group of interested parties to form [an antecedent of] today’s American Craft Council.

What was the national craft scene like before Mrs. Webb came along?

What Mrs. Webb found out in running Putnam County Products was similar [to what was happening] elsewhere in the United States. In the early 1930s there were some university-level schools that taught craft media, at Cranbrook and the University of Kansas, for instance. There were graduates of these schools as well as some holdovers from the arts and crafts era, but on the whole, these people were scattered around the country with little connection to one another. The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston (founded 1897) had made great headway during the early decades of the twentieth century, and the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen (founded 1932) had regional success, but a strong national organization was lacking.

In Mrs. Webb’s lifetime, the definition of “craft” and “craftsperson” changed. How did that come about?

From my perspective, Mrs. Webb was primarily engaged in improving networks among artists, and creating educational and exhibition opportunities for them. Her museum staff, particularly Paul Smith, who later became director, had a much closer connection to the makers. Paul was in constant contact with artists around the country and his exhibitions reflect the changing nature of the field, particularly in the 1960s as the notion of a craftsman expanded from someone involved in limited production to the one in studio environment who creates singular works of art.

Tell us about any individual artists she may have championed.

She did not leave a record of opinion about particular artists, but the Museum has some wonderful works that she had in her personal collection, which offers us a glimpse into Mrs. Webb’s taste and perhaps her personal relationships with some artists. These include ceramics by Beatrice Wood, Peter Voulkos, Toshiko Takaezu, and Marguerite Wildenhain, perhaps because she enjoyed making pottery herself. She also owned enamels by June Schwarcz and furniture by Wendell Castle.

What was her connection to the ACC Gold Medalists in the show?

Without the organizational network that Mrs. Webb provided, most of the ACC Gold Medalists would not have been able to reach their fullest potential. Thanks to their involvement with Craft Horizons [now American Craft], ACC conferences, and museum exhibitions, these talented men and women reached a wide audience of makers and collectors around the country. The ACC Gold Medalists are artists who are deemed by their peers to have achieved the highest distinction in their particular medium, and along with this recognition are the lives they touched through their example.

The Museum is well suited to display the works of the Gold Medalists, as we own many works by them. We plan to dedicate a lot of space to these artists, among them blacksmiths Albert Paley, Brent Kington, weaver Kay Sekimachi and her woodturner husband, Bob Stocksdale, and ceramist Stephen De Staebler. We will include some ravishing jewelry by Arline Fisch and John Paul Miller.

What are some of the objects you’ve chosen to help tell her story?

The Museum of Arts and Design has the perfect collection to trace the history of her leadership in the American craft movement. We will be including works shown in the very first exhibition mounted by the American Craftsman’s Educational Council (an ACC ancestor), in association with the Brooklyn Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, which was called Designer Craftsman U.S.A. 1953. We will show a set of rattan stools by John Risley, a Cranbrook graduate who spent time teaching craftsmen in the Philippines. There will be works of art by Wendell Castle, Hans Christensen, and Jack Prip, professors at [what became] the School for American Crafts, which she first founded at Dartmouth College [as the School of for American Craftsmen], and which now resides at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Wharton Esherick will be included, as he was the first person to receive a one-man show at the new Museum of Contemporary Crafts (today’s MAD). There will be a marvelously diverse group of objects that date from the era of Paul Smith’s directorship [of the museum, 1963 – 1987]. Among these are ceramics by Robert Arneson and Jun Kaneko, and textiles by Jack Lenor Larsen.

Mrs. Webb had a pottery studio in her home and also was a painter, woodcarver, and poet. Will any of her own work be on view?

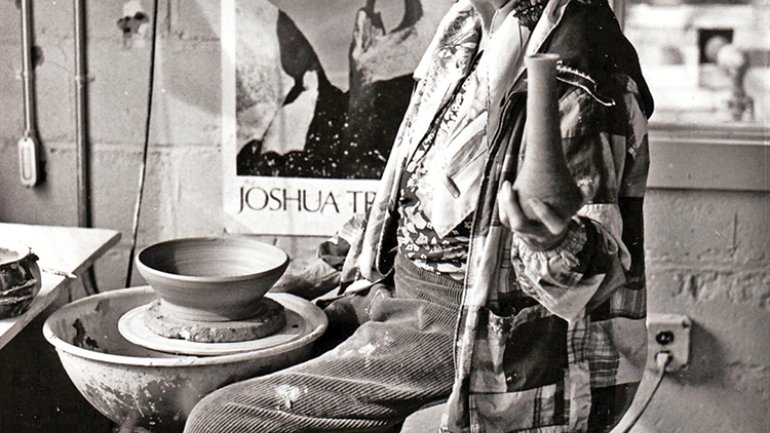

Like many artists, Mrs. Webb described herself as being “always interested in using my hands.” As a young woman she painted, produced watercolors, and made woodcarvings, and I believe that she began to enjoy pottery sometime after 1948, when she provided funds to build a ceramics studio at the Shelburne Craft School in Vermont. One of our favorite photographs shows her seated at the potter’s wheel at the Shelburne school while holding up a vessel that she has just made. Taken together, they help us form an image of Mrs. Webb as a person who valued the process of making, whether avocationally or professionally. The Museum has a few modest examples of her pottery that may be in the exhibition, and they can also be seen online.

Who are the contemporary Mrs. Webbs, out changing and expanding the craft universe right now?

We are fortunate that there are a number of dynamic individuals who are vitally engaged in building meaningful museums and organizations that advance the craft world. Ruth Kohler runs the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where she has embraced the work of vernacular artists in craft media as well as contemporary makers seeking a collaboration with the Kohler Co.’s industrial resources. Ruth is particularly interested in preserving Wisconsin craft as well, so her activities represent a local as well as national thrust. Another craft activist is Marion “Kippy” Stroud, who created a textile atelier called The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. The workshop offers valuable space and technical assistance to artists wishing to execute new work.

Broader financial support for catalogues, exhibitions, acquisitions, and publications has come from the Windgate Foundation. Many organizations, MAD included, are indebted to Windgate for their generosity over the years. Our exhibition will include some extraordinary works purchased with Windgate funds, such as the magical Story Book by Michele Holzapfel.

The philanthropist Nanette L. Laitman generously funded 235 oral histories of American craftsmen, most of which are now posted online at the Archives of American Art’s Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. You can read first-person accounts of their journeys as craftsmen and designers, learn their struggles and triumphs, and chart the evolving state of our field. Their words form a valuable and indeed irreplaceable repository of our own history.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the show?

Our show will be divided into two parts.The first will address the era of Mrs. Webb, and will include works of art by artists represented in exhibitions through the 1960s, or who taught at the School for American Craftsmen, or participated in the World Craft Council. The second half will enforce the ongoing activity of craft advocates who have enabled the field to move forward. We will feature the ACC’s emphasis on excellence in craft with works by Gold Medalists like Betty Woodman, who is being honored this year. Works of art by makers who were interviewed for the Laitman project at the Archives of American Art will be included. The show concludes with objects in MAD’s collection that were made in the last decade, such as stained glass artist Judith Schaechter, among others, acquired with funds from the Windgate Foundation.

And finally, we’re dying to know: What would Mrs. Webb do?

In telling the story of Mrs. Webb, we are really trying to reach out to those who often feel that they can do little to effect change in our field. In fact, Mrs. Webb was only the tip of the spear; she inspired untold numbers of people across the country to get involved. But as you know, there is so much to do today in terms of writing, outreach, organization, fundraising, as well as making. It takes many hands – philanthropic, paid, and volunteer– to make it all possible.

I sometimes call Mrs. Webb our mother, but she was more like a midwife; she made it possible for the modern studio craft movement to flourish. If she were here today, she would probably be planning conferences and bringing new generations of artists, collectors, and advocates together to advance American craft and design. We hope that our exhibition will encourage people to realize that they absolutely can make a difference, whether it is on a local or national level. Thank heavens for Mrs. Webb, and thanks to all who give of their time and funds to continue her work.

"What Would Mrs. Webb Do?" runs through February 8. Barbara Haugen is the shows editor and a frequent contributor to American Craft.