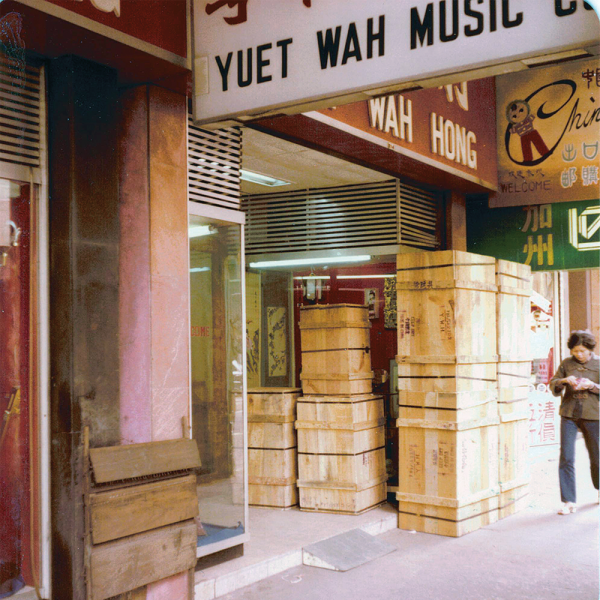

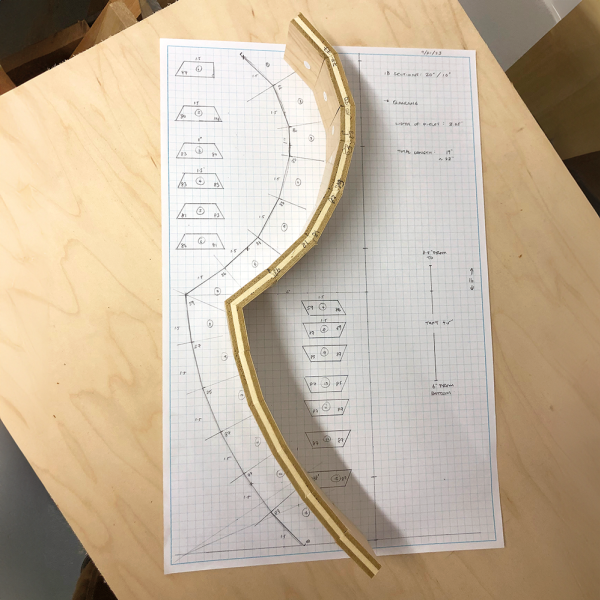

The cargo arrived in January 2023: a truckful of hardwood panels, driven from Manhattan’s Chinatown to Richmond, Virginia, where Vivian Chiu received them at her studio. Stenciled on their weathered surfaces were numbers and a shipping company’s name, in Chinese characters—marks of their past lives as crates that ferried Chinese porcelain and other wares across the Pacific to America. In Richmond, they were raw material for Chiu, an artist and woodworker, who sized up her challenge ahead. “None of it was straight or flat; the wood was warped; it had different thicknesses,” she says. “It carried the mark of human hands.”

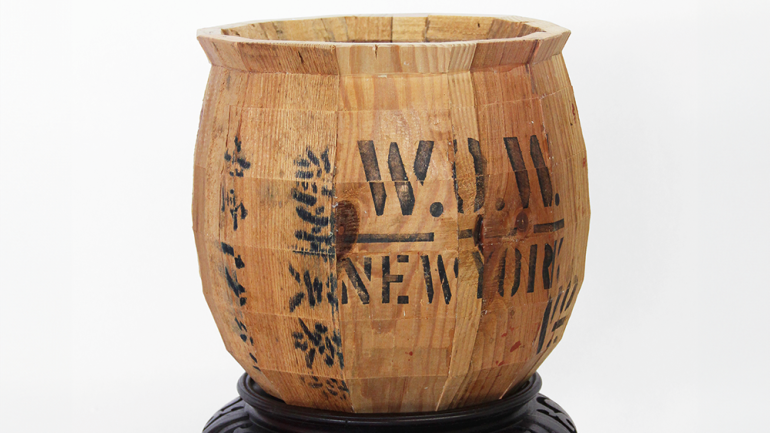

By that summer, Chiu had transformed several panels into sculptures through her own labor-intensive process. The wood is no longer rough-edged but streamlined, contoured into elegant replicas of traditional Chinese vases, from pear-shaped vessels to a bulbous double-gourd piece. They are tributes to not only the crates’ former contents but also the business that for decades received those shipments, before finally gifting the crates to Chiu: Wing On Wo & Co., the oldest store in New York City’s Chinatown, managed today by fifth-generation owner Mei Lum.

Left unfinished to display traces of their utilitarian pasts, Chiu’s sculptures evoke the intertwined migration paths of objects and the lives of those who’ve cared for them. “By elevating this material, I’m elevating the journey of how they came to America, and how Mei’s family did that immigration journey,” Chiu says. “I’m paying homage to everyone who’s made that journey, including my parents.” They and Chiu’s grandparents “were the crate,” she adds, “and what wear and tear they endured to protect me.” She titled the series Passages (those that carried us).

Born in Los Angeles, Chiu emigrated to her ancestral homeland of Hong Kong at age 3. She returned to the US to study at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she majored in furniture design and found her love of woodworking. “It’s the language I speak most clearly in,” she says. “I love the tools, and my hands and brain gravitate toward the techniques.” After graduating in 2011, she moved to New York to assist the sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard and later enrolled in Columbia University’s MFA program. Her work has always drawn on personal experiences, reflecting in particular her identity as a queer Asian American: undulating, split-turned sculptures that explore tensions of desire and subjectivity; interlocking, abstract forms whose optical illusions play subtly with notions of camouflage and passing.

More representational, Passages is a formal pivot. It is also Chiu’s most outward-looking project yet, evoking generations of upheaval, separation, and arduous rebuilding that diasporic groups experience as they seek better lives outside their home countries. “The material is the main character,” she says, noting that it symbolizes a long span of time and many, many people. “This was me speaking through this symbol. . . . I was the vessel for this story.”

Chiu arranges crate pieces in her studio in Richmond, Virginia.