The gray sea light of Port Townsend, Washington, washes through the window of Maureen Walrath’s barn loft studio. Goats and chickens squabble below. Bundles of cured willow hang along the slanted eaves in shades ranging from butter to molasses, the possibility of a hundred baskets held within them.

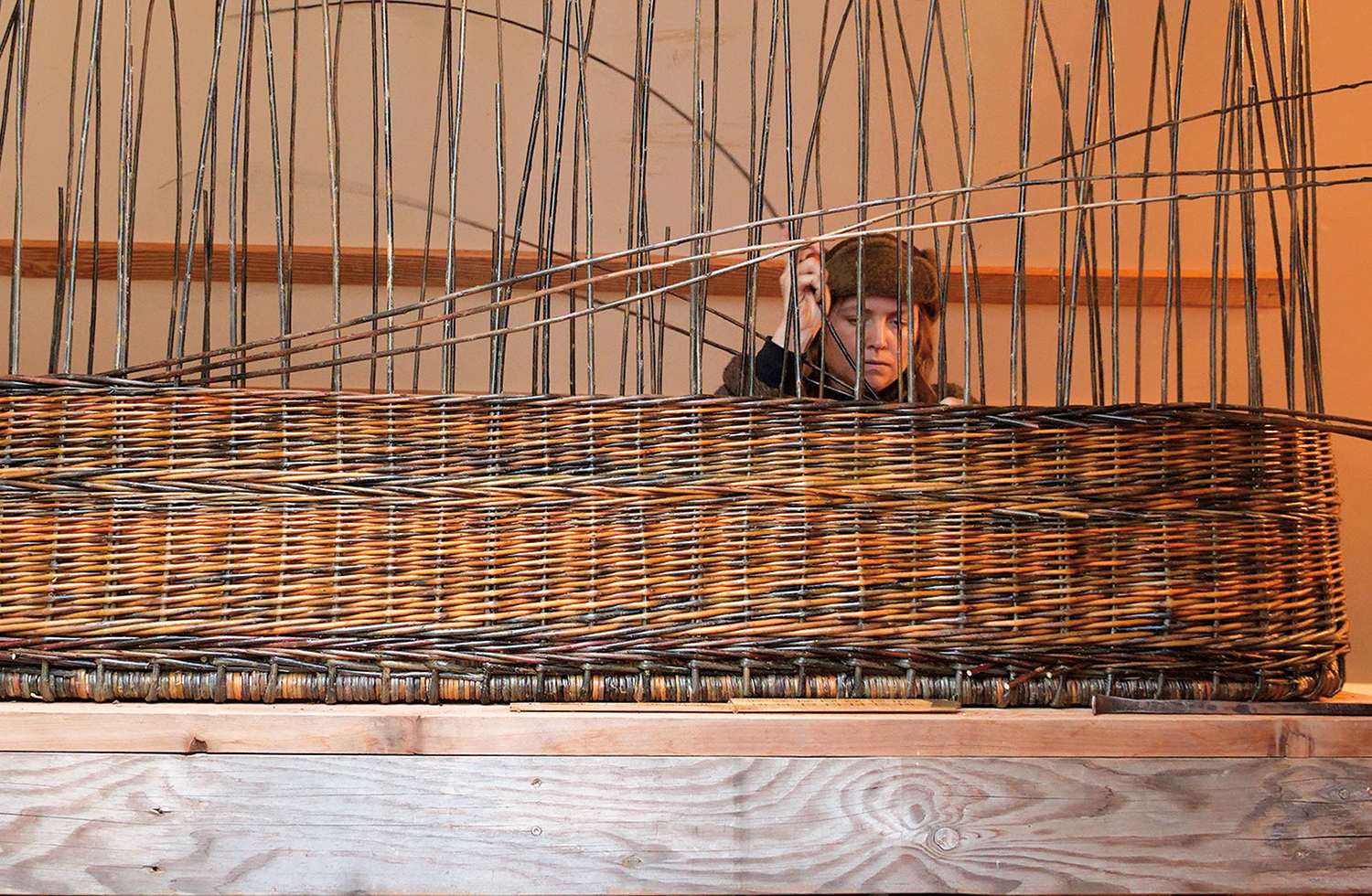

On a long wooden table in the middle of the room, a willow coffin grows row by woven row. Walrath’s hands move in a steady rhythm set by the low tune she hums. The otherworldly light casts shadows that pool in the emerging spaces, in the ridges between the willow rounds, in the coffin’s long mouth. The shadows ask of everything they touch: what can you hold? Walrath herself carries the swimming promise of her unborn child. She reaches out to weave over her growing belly.

A gentle inquiry into the art of holding is at the heart of Walrath’s craft. “I love considering the whole picture when I’m making these vessels, of how they’re going to hold someone,” she reflects. “Both how they’re going to hold the one inside and also how they’re going to hold the space for those who surround the basket.”

Originally from Chicago, Walrath worked in arts education until a pull to live closer to the land led her to a series of intentional communities in Missouri. There, inspiration tugged at her sleeve again. “I came to baskets very intuitively,” she recounts. “It was a very spontaneous messenger that just said ‘baskets.’”

A friend connected her with Oregon-based ethnobotanist and basketmaker Margaret Mathewson, but Mathewson wasn’t taking on apprentices at the time. She did, however, offer Walrath another option. “She told me, ‘Well, you could just get on a train and come out here. Bring a sleeping bag and a knife.’ That’s where my relationship with willow started, where the willow rhythm entered my life.”

Walrath’s days continue to move at a pace set by willow. “It has become a part of who I am. Not necessarily as an identity, but as part of my seasonal and yearly rhythm.”

Alongside her creative practice, Walrath has guided members of her community through their most intimate transitions as both a birth and a death doula. These liminal landscapes inform her work. “Ancestral crafts like basketry have a way of being a part of everyday humanness, of living with human culture,” she says. “There’s a natural, organic connection with birth and death work. The practice has within it this ancient tendril: we’ve always been weaving baskets, we’ve always been tending to birth and showing up at the threshold of death.”

Walrath harvests willow in November, the dormant season, in Salem, Oregon.