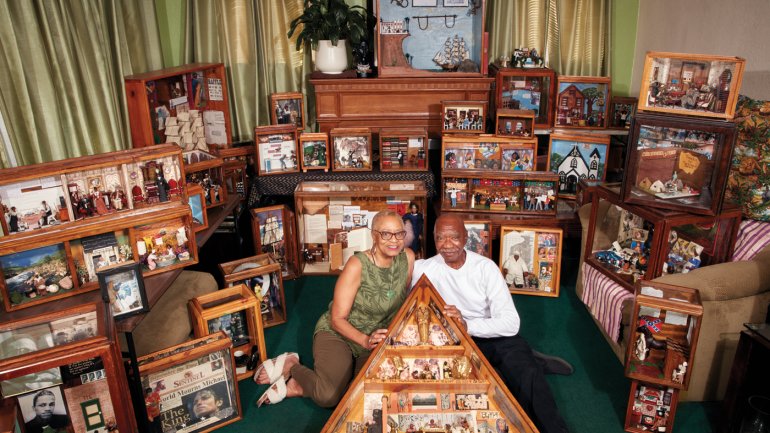

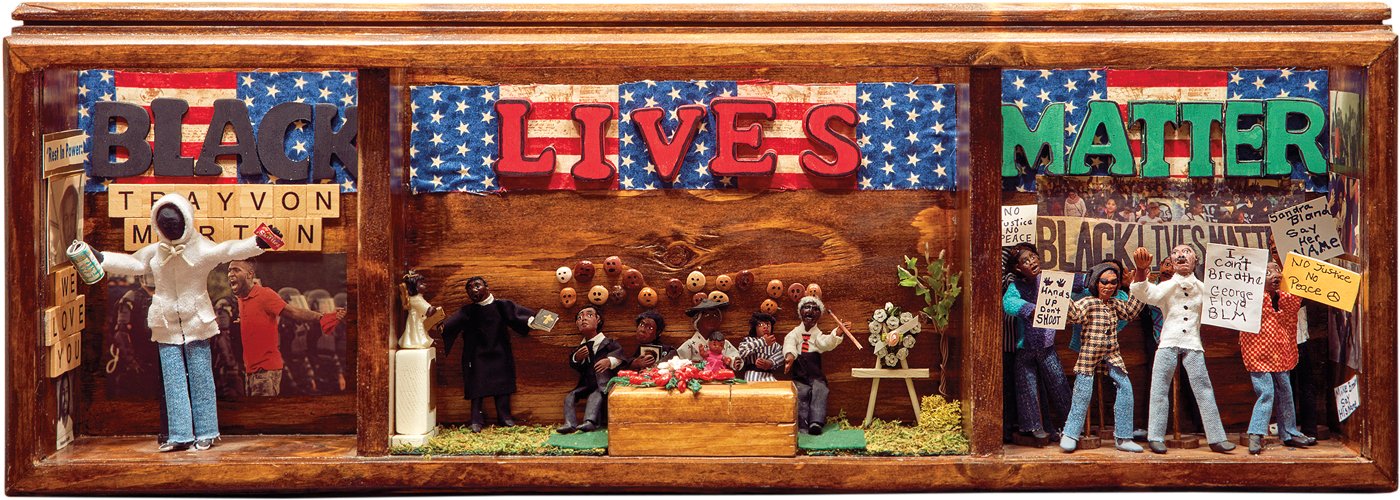

Collins’s singular work has earned an enthusiastic following. Recently, she created a series of dioramas depicting Black cowboys and scenes from the life of an early Black U.S. Marshal for the Autry Museum of the American West. Her dioramas—each intricately constructed within a rectangular “shadow box” with shallow wooden walls—capture dozens of pivotal moments rendered in three dimensions. Most contain miniature clay renderings of influential Black activists, entrepreneurs, and political leaders, as well as families enjoying hard-won victories in the face of widespread abuses.

Born in 1952, Collins came of age on Indiana Avenue, the center of Black life in 1950s Indianapolis. She remembers strolling with her siblings down the avenue on Saturdays and taking in the smell of barbecue, the sound of live music, and the hubbub from various Black-owned businesses. Across the street from Collins’s home in Lockefield Gardens, one of the nation’s first public housing projects, stood the manufacturing plant belonging to Black hair mogul Madam C.J. Walker, one of the most successful female entrepreneurs of her time. Collins remembers wandering the Walker Building’s commercial area, which included a beauty salon, an auditorium, a drugstore, and a restaurant. “It was all open inside,” she says. “You could see inside the salon; you could watch the women with their shampoo bowls tending to their clients. It was an opportunity to see Black professionals at work, contributing to the neighborhood.”

Collins celebrates and perpetuates Walker’s legacy through her work. Two distinct shadow boxes—now housed in the Madam Walker Legacy Center at the former manufacturing plant—commemorate Walker’s journey from rags to riches. One shows Walker standing proudly before a fireplace and gilt-framed flower print, wearing an elegant dress made of fabric and lace, a tiny string of pearls around her neck.

Collins’s love of miniatures developed early and flourished under constraint. “My mother couldn’t afford a dollhouse, so I would build them out of cardboard boxes for me and my sisters,” she says. “I would repurpose White Castle carrying cases for the furniture and tear off squares of toilet paper to make the beds.” Dolls, too, were expensive, so she cut them out of paper, along with the clothing she designed.

Collins participated in much of the history she now teaches through her work. She attended meetings at the Black Panthers’ Midwest headquarters. When she protested her high school’s restrictions on cultural expression, she was jailed with other students. She was elected president of the NAACP youth council in Indianapolis, which afforded her the opportunity to travel. “That gave me a sense of us as a people,” she says, “of where we’d been, of how far we had come and how far we had yet to go.”

In 1971, Collins followed her family to Compton, where she met her husband and collaborator, Eddie Lewis. Her obsession with miniatures intensified when, in the 1990s, her son was arrested just before his high school graduation. “I began creating these scenes because I wanted another chance to teach children about their worth as human beings,” she says.

At first, she and Lewis put scenes inside wooden cigar boxes. “It was just furniture then, no people,” she says. “Maybe somebody played cards and the cards were lying on the table. I’ve seen miniatures that are exquisite, but they don’t have people in them. If I’d studied interior design, maybe I’d feel differently. But for me, they need to have people to tell the story.