After moving to Plainwell, Michigan,

a town of about 4,000 residents on the banks of the Kalamazoo River, artist Norwood Viviano realized that nearly everyone he met had in some way been affected by the paper mill industry. The Plainwell Paper Mill, established in 1887, was the town’s beating heart until it declared bankruptcy and shuttered its plant two decades ago.

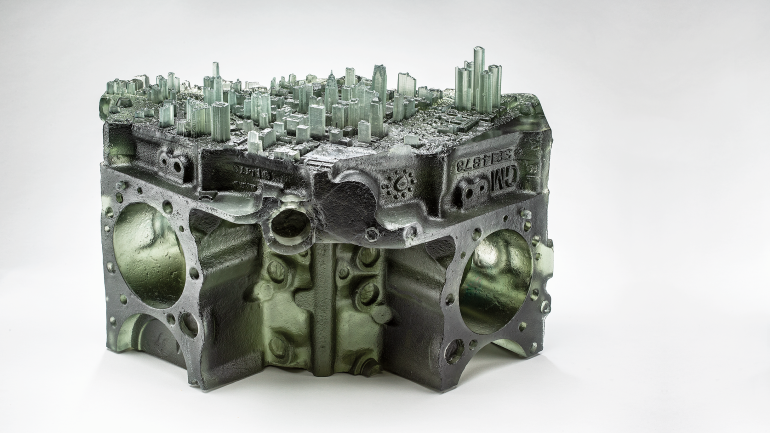

Viviano chose Plainwell in 2005 to be close to Grand Valley State University, where he teaches sculpture, and because it seemed like a tranquil and affordable place to raise a family. Being there, he says, made him think more deeply about the “ties between industry and community and the hierarchies at play,” leading him to create a series of metal sculptures called Recasting Michigan. The sculptures showed, in a tactile way, the population shifts that have taken place since the industrial revolution in manufacturing cities across the state. “That was my first foray into experimenting with data,” he says of the works, completed between 2009 and 2011. “Most people would walk right by raw statistics, but if you make it three-dimensional, it has an ability to draw you in.”

One of the sculptures, made of cast and machined aluminum, has an angular, geode-shaped base representing Detroit’s population growth and decline over time (it peaked in 1950), and a flat top showing a detailed three-dimensional portrait of the city as seen from the air. Carving it required a computerized mill and took 300 hours.

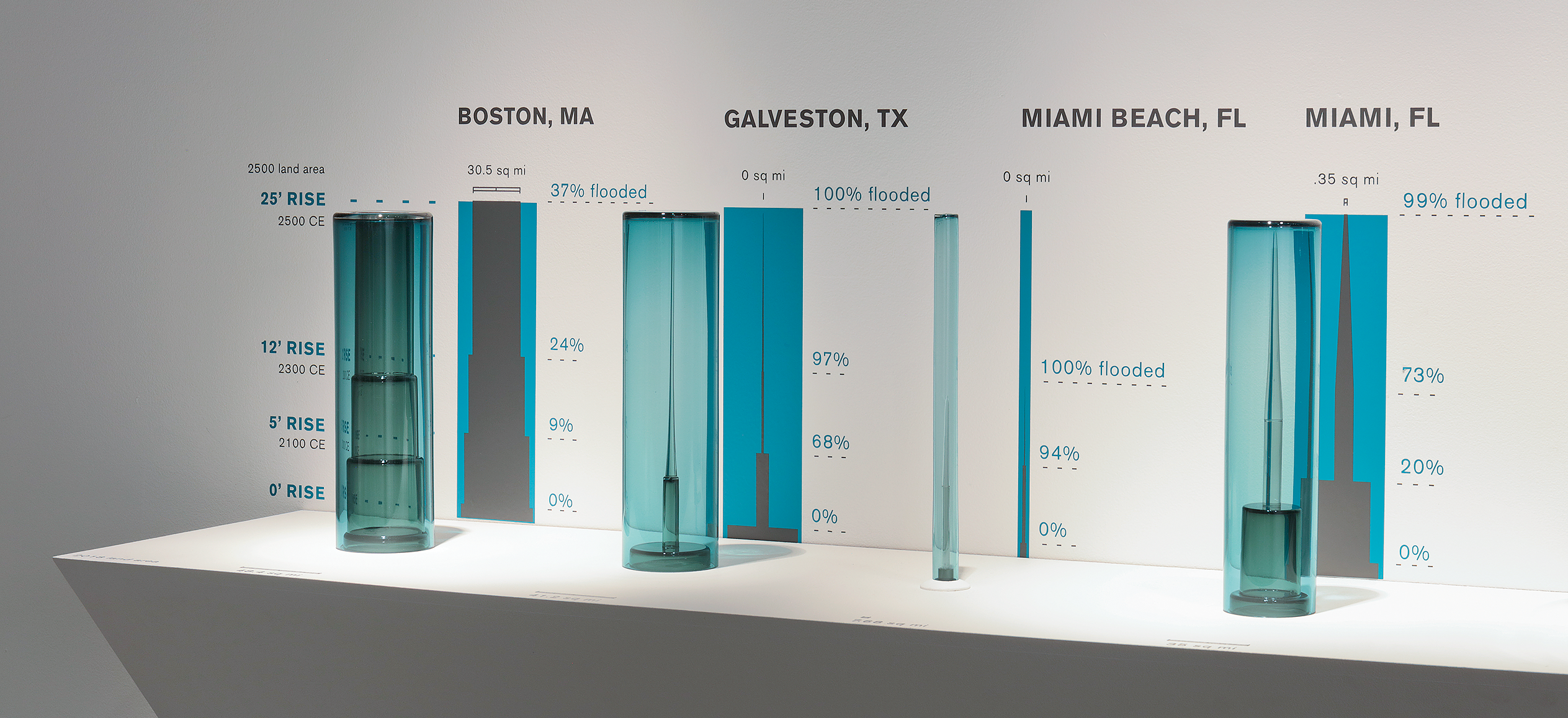

Viviano is part of a group of sculptors and craft artists who are using statistics and data in their creative processes. The themes they deal with are varied, yet they seem unified in their goal: to help people understand important social, political, and environmental changes that occur over long periods of time.

“Craft is really effective at providing accessible pathways to understanding the world around us,” says Beth C. McLaughlin, artistic director and chief curator at the Fuller Craft Museum in Massachusetts, which recently unveiled an exhibit called Material Mapping: Data-driven Sculpture by Adrien Segal & Norwood Viviano, on view until March 2024. “Humans have been using their hands to convey information for thousands of years, and incorporating data is a way of expanding this tradition.”

McLaughlin says she is seeing more and more craft related to data, as well as significant interest from collectors. Although the trend is hard to quantify, there is anecdotal evidence supporting a growing link between facts and statistics and craft, including the publication this year of Making with Data: Physical Design and Craft in a Data-Driven World (CRC Press), which presents more than two dozen contemporary designers, researchers, and artists who are using data to produce objects, spaces, and experiences.

Norwood Viviano’s Detroit Population Shift, 2009, CNC machined and cast aluminum, 36 x 26 x 18 in. The piece, which depicts Detroit’s changing population over time, took hundreds of hours to carve and required a computerized mill.