Wearing a plaid shirt and a tool apron, renowned pipe organ builder Martin Pasi sits at a large wooden workbench littered with tools and an unnervingly hot soldering iron, rolling sheets of lead-tin alloy into a pipe. “We are going to put a bevel on the edge here,” says Pasi, who recently moved his shop from Roy, Washington, to the grounds of Saint John’s Abbey, a Benedictine monastery in Collegeville, Minnesota. “Everything needs to be very clean. This is 28 percent tin and the rest lead. The tin is in there to strengthen the lead up.”

The alloy sheets, formed in-house, are coated with sizing, a white powder made of gum arabic and chalk. “It protects the metal from burning,” says Pasi, rubbing the edges with wax. “When I’m soldering, the metal is very close to the solder. It wants to melt. But we don’t want it to. So that’s why we protect it with a sizing. It washes off really easily with warm water. This is an ancient method.”

Pasi uses a series of mandrels—basically, metal rods—to roll and shape the pipe, all the while banging on it with a piece of wood. Then he reaches for the soldering iron and carefully dabs the edges to seal them. “Now, the temperature and the speed with which I’m doing this is all-important.”

Pasi goes through the remaining steps of making a finished pipe—trimming, filing, soldering, forming the “lip,” cutting the “mouth,” adding a flat plate called a languid to control the angle of air flow—with the skill of a master. “Just the sound itself” drew Pasi to organs as a kid in his native Austria, he says. “It’s unique. It tries to imitate orchestral instruments. But, of course, it’s only an imitation. So it’s really its own thing.”

Hand-building an organ takes between a year and a half and two years. Currently, Pasi and his crew are making one for a church in Leawood, Kansas, that will have more than 3,000 pipes. “And the beautiful thing about pipe making and organ making in general is it’s a lot of handwork, still,” Pasi says. “It’s not something you can automate, because each pipe has a different measurement.”

Pasi is one of just a handful of pipe organ builders in the US who make these hulking instruments using the old ways. He first came to Saint John’s in 2019 to oversee an expansion of the abbey church organ, which involved creating thousands of new metal and wood pipes. The project, completed in 2020, boosted the sound in the church, a stunning Bauhaus-style structure built in 1961—arguably the heart of a campus that includes a university, a preparatory school, and 2,500 acres of woods and lakes.

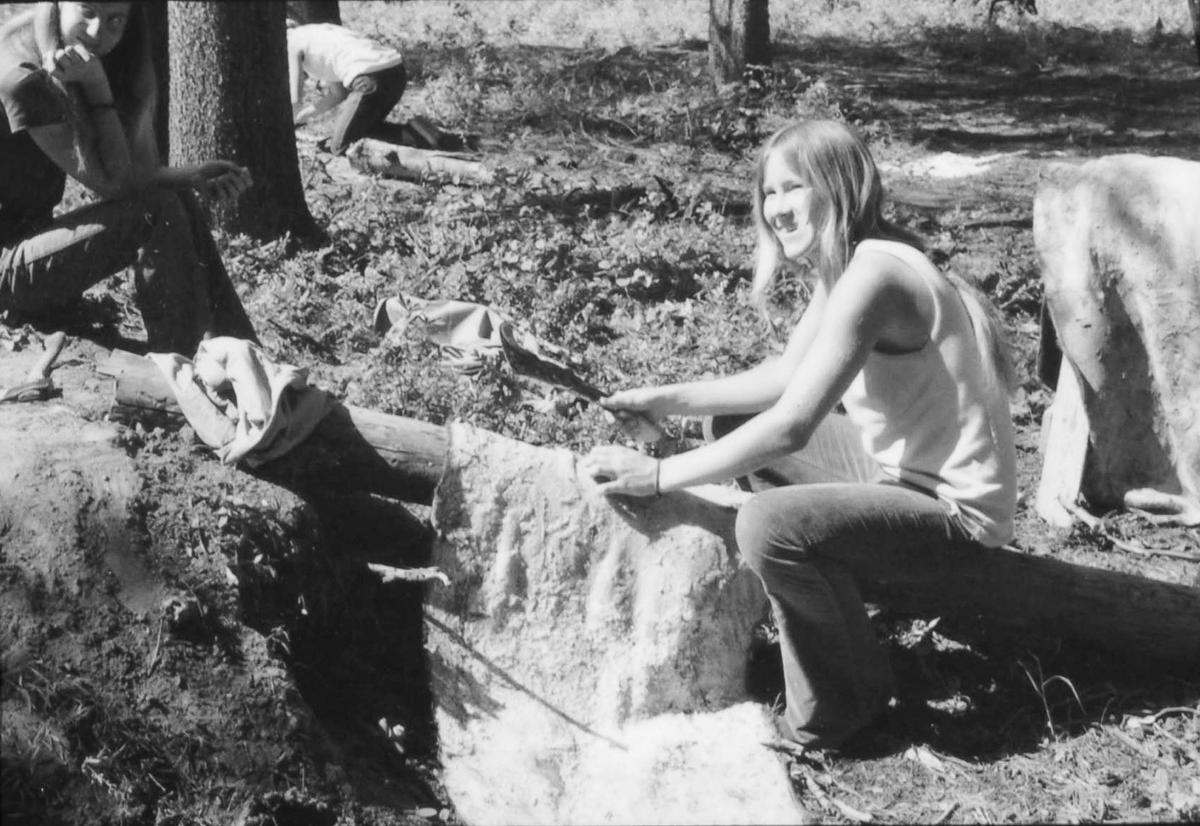

Pasi, who moved from Washington to Collegeville, Minnesota, solders a lead-tin alloy organ pipe.