Stories

News, stories, and in-depth features on the artists, makers, organizations, and trends shaping the craft community.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

334 articles

-

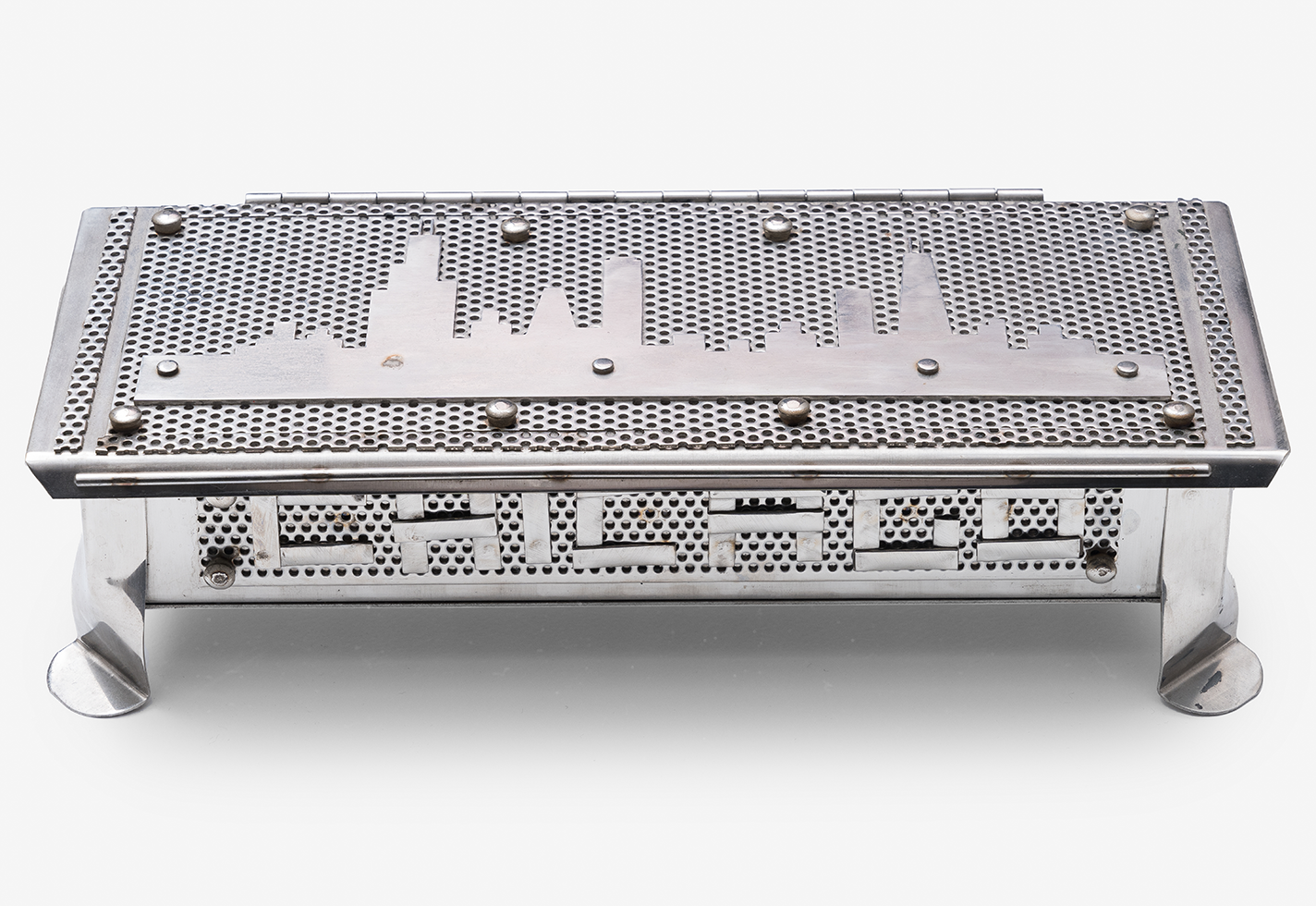

The Queue: Margaret Jacobs

Margaret Jacobs’s organic forms in steel and brass draw on influences from her Akwesasne Mohawk heritage.

Digital Only

JewelryMetal -

Explore Craft Around the Country with ACC’s Regional Craft Correspondents

The four writer-artists of ACC’s new program take readers deep into their region’s craft scene.

Digital Only

-

Handwork 2026 is a National Celebration of Craft 250 Years in the Making

Arts organizations find community, partnership, and collaboration through Craft in America’s landmark initiative.

Digital Only

EventsExhibitions -

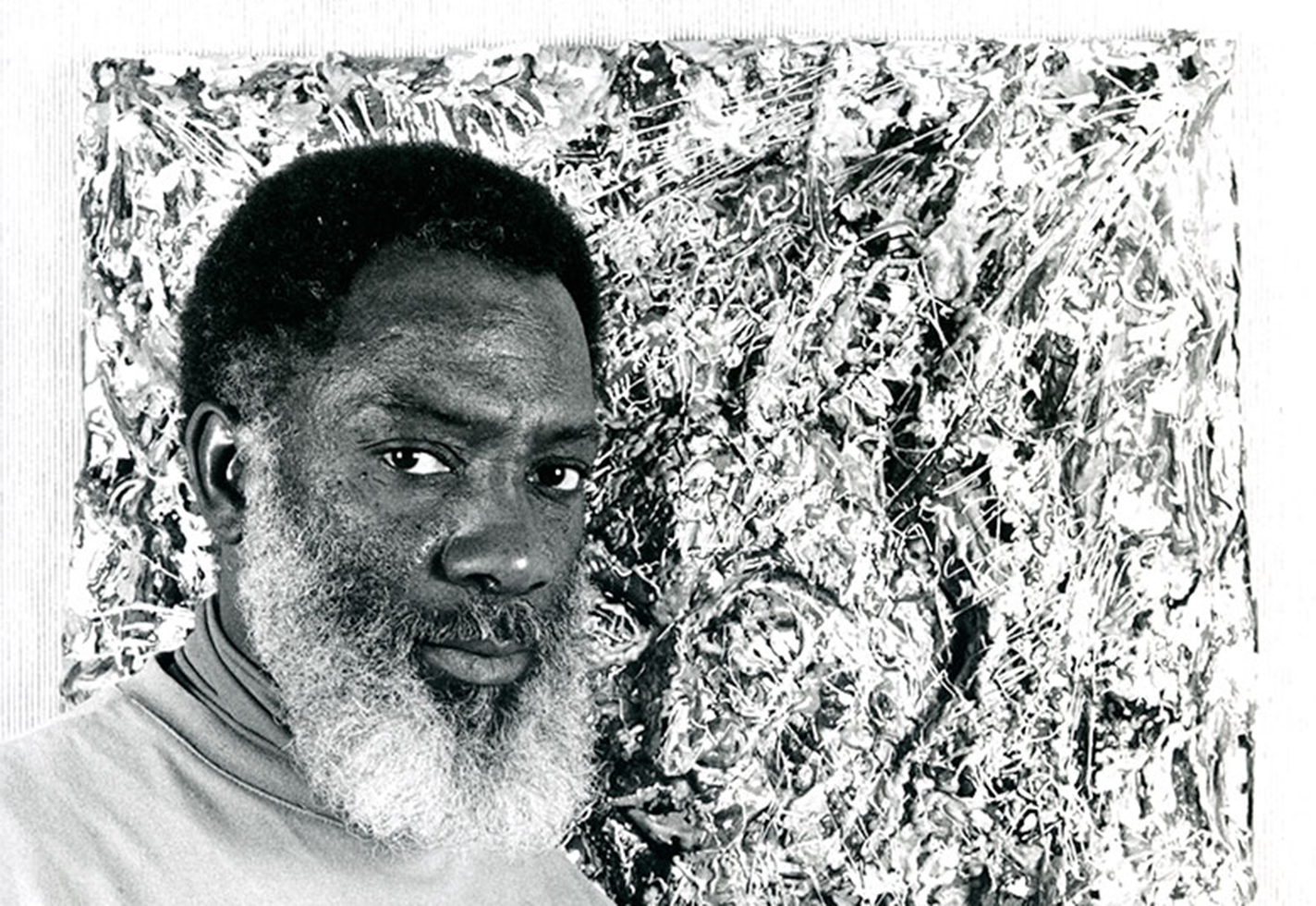

In Memoriam: James L. Tanner

The American Craft Council remembers 2003 Fellow James L. Tanner, who died in January.

Digital Only

CeramicsEducationGlass -

“What About Wood?”: VCUArts Furniture Design Concentration Under Threat

Furniture makers and members of the craft community express dismay over the university’s repositioning efforts.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

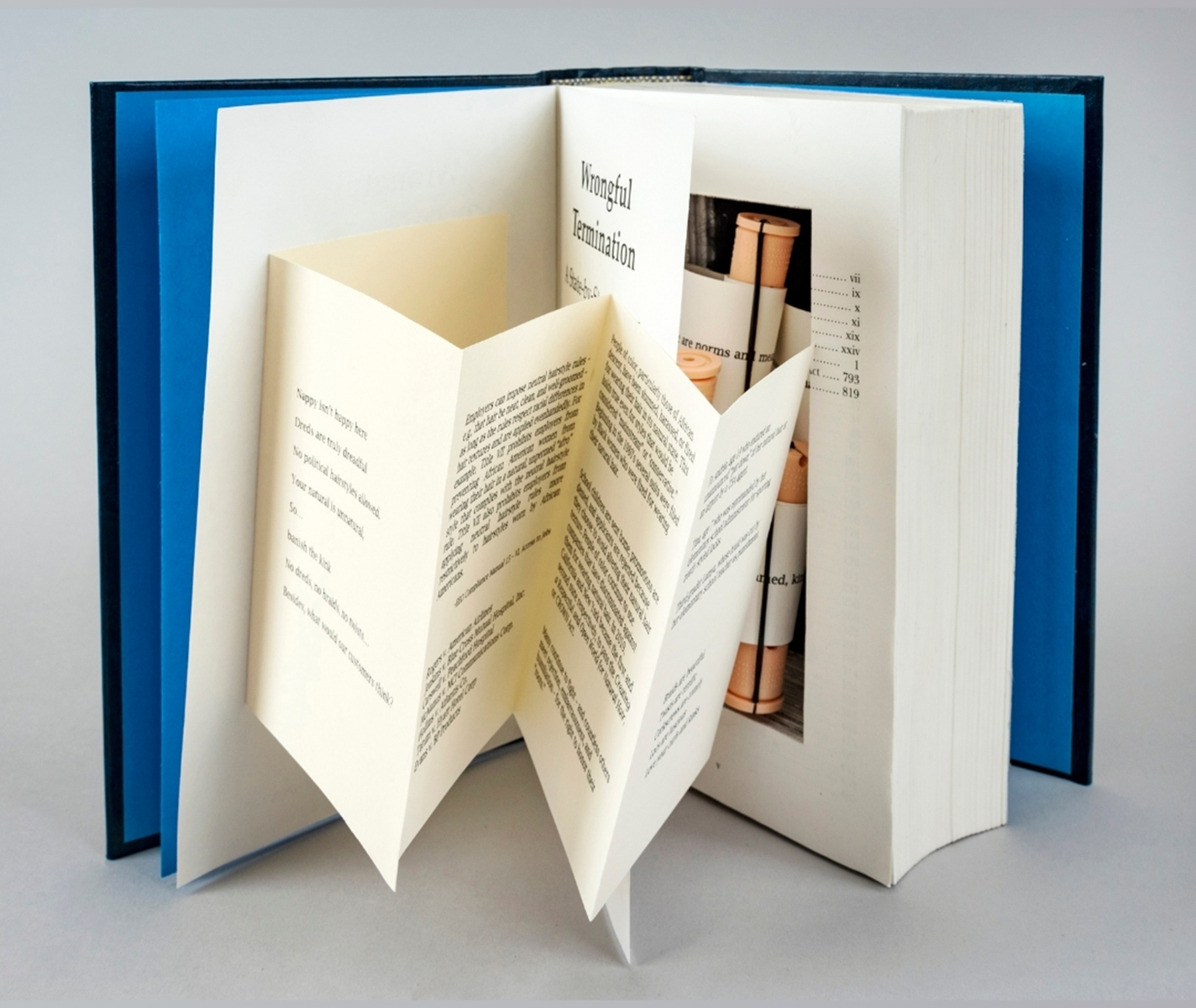

A Library That Holds More Than Books

In Los Angeles, Heavy Manners Library offers affordable craft workshops and a space for creative meandering.

Digital Only

ClothingEducationFiber & TextilesMixed Media -

Figures in the Fold

Bianca MacPherson digs into the archives for inspiration for her undulating stoneware and porcelain sculptures.

Digital Only

Ceramics -

Repurposed Materials, Reclaimed History

In Gloria Martinez-Granados’s cross-stitched portraits, the stories of Latino laborers stretch across generations.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

Jane Yang-D’Haene Shortlisted for the 2026 Loewe Foundation Craft Prize

Representing the United States in a global cohort of 30 finalists, the New York–based ceramist's work combines expressive, personal surfaces with traditional Korean forms.

Digital Only

Ceramics -

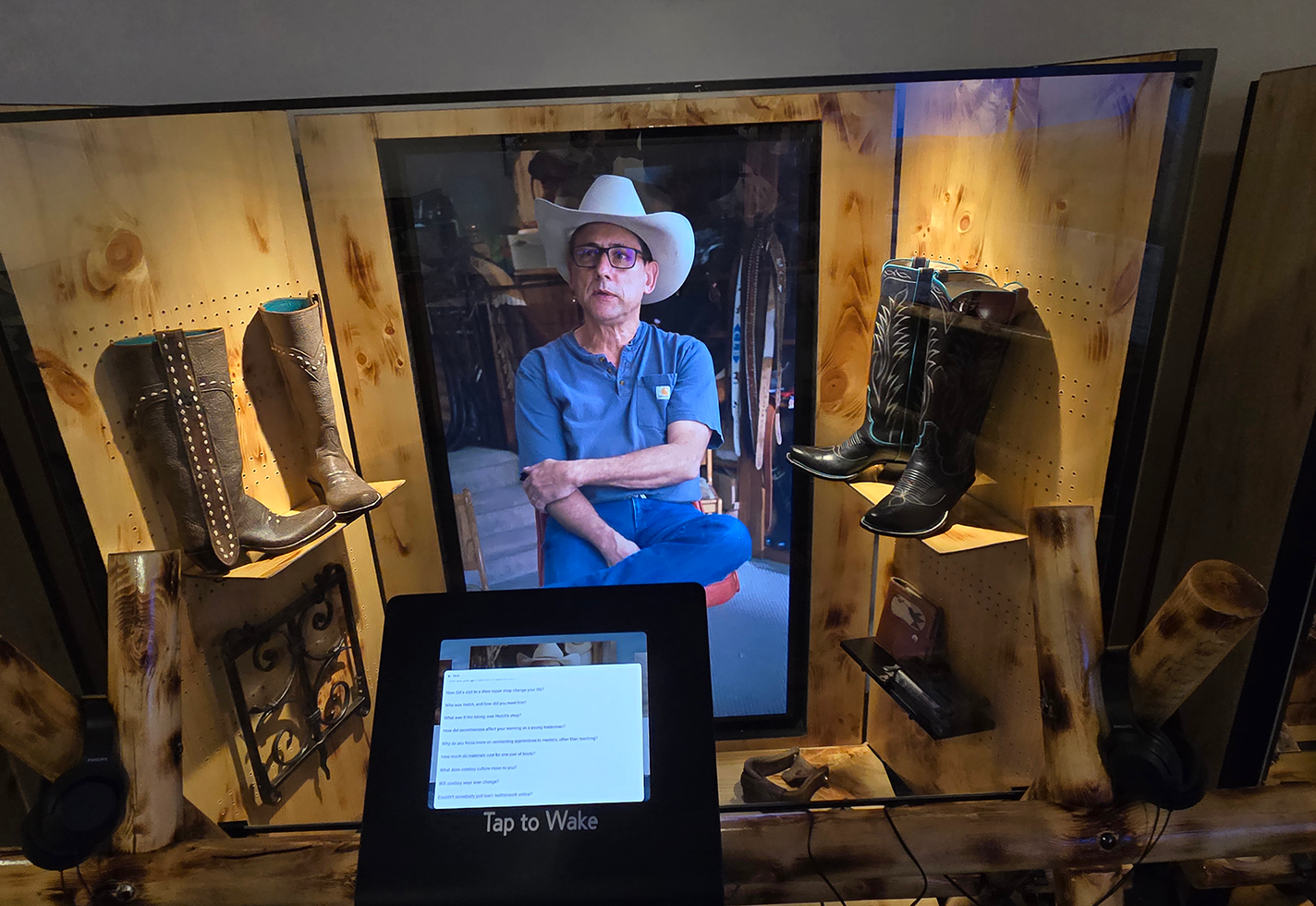

At the Cowboy Arts and Gear Museum, A Contest and Auction Forged in Tradition

The Cowboy Arts and Gear Museum’s annual Bits and Rawhide Reins Contest and Auction celebrates Western craftsmanship.

Digital Only

Fiber & TextilesMetal -

At Home on the Range

A traveling exhibition from the Cowboy Trades Association brings Western tradecraft to audiences across the western US in 2026.

Digital Only

ExhibitionsFiber & TextilesMetal -

A Craft Community in the High Country

The Rocky Mountain Folk School fosters year-round creativity and a pathway to Western trades high up in the mountains.

Digital Only

CeramicsFiber & TextilesGlassMetal -

Silver River Weaves Again

After a devastating flood, the North Carolina chair caning institution returns in a new space.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

In a Chicago Exhibition, A Focus on Migration and Self-Taught Artists

Craft mediums feature prominently in Catalyst, an exhibition spotlighting self-taught immigrant artists at the Intuit Art Museum.

Digital Only

Exhibitions -

Crafted in the Mountains Traces the History of Appalachian Craft

A new exhibition at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts considers the shifting landscape of craft in the region.

Digital Only

Exhibitions -

A Clothing Designer’s Careful Dance

Pittsburgh designer and maker Rona Chang balances family life and running a sustainable clothing brand.

Digital Only

ClothingFiber & Textiles -

In Glass Objects, A Radiant Optimism

SaraBeth Post Eskuche channels color and energy into her vivid glass jewelry, home wares, and sculptures.

Digital Only

GlassJewelry -

A River Runs Through It: Water | Craft at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum

In a new exhibition at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum, seven craft artists explore material history, generational knowledge, and ecological lament through an aquatic lens.

Digital Only

BasketryExhibitionsFiber & TextilesMixed Media -

Worn on the Body

A new exhibition at Kansas City’s Belger Crane Yard Studios celebrates handmade adornment.

Digital Only

ClothingExhibitionsJewelryMixed Media -

A Patchwork of Peace

Buddhist monks walk across the US draped in robes rich in history and community.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

A Delicate Balance

The founder of A Nod to Design pairs beads and chains in her harmonious jewelry designs.

Digital Only

GlassJewelryMetal -

Furniture Problems, Artfully Solved

Eric Carr aims to satisfy unique client needs with his fine studio furniture.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

Valentine’s Day Iron Pour Welcomes Metalsmiths and the Metal-Curious

Collaboration, mentorship, and experimentation are at the heart of Pour’n Yer Heart Out, an annual community event in Wisconsin’s capital city.

Digital Only

EventsMetal -

Crafting Your Legacy: A Curator’s Perspective

In the inaugural column of our Craft Coalition series, the Everson Museum of Art’s ceramics curator explains how artists can get their work into museum collections.

Digital Only

Story categories.

-

Craft News

Timely, topical stories on the artists, makers, and organizations shaping the craft field.

-

Interviews & Profiles

Inspiration and insight from and about makers.

-

Features & Essays

Expert voices dig deep into craft-related subjects.

-

Craft Around the Country

Regional craft reporting and storytelling.

-

Craft Media

Books, periodicals, videos, and podcasts highlighting craft.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.