All His Own

All His Own

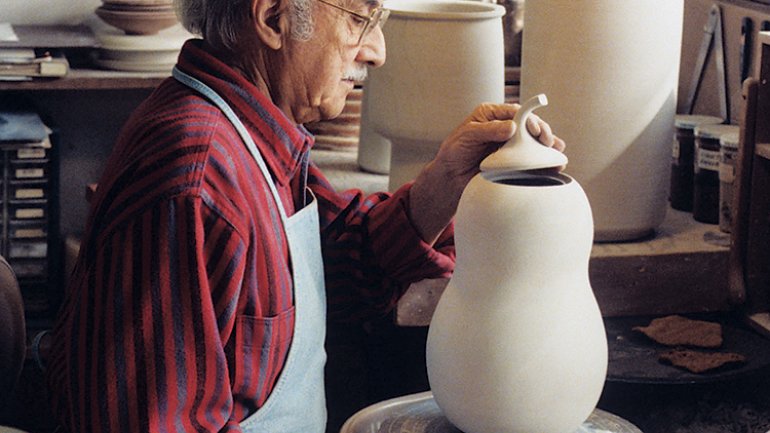

“I have 99 years of experience,” proclaims Harrison McIntosh; “I try to remember things.”

And remember he does. The nonagenarian ceramist and Fellow of the American Craft Council can recount his earliest experiences with art as an elementary school student in Stockton, California. Alongside his brother, Robert, McIntosh experimented with painting throughout his youth, mentored by local landscape artist Arthur Haddock. It wasn’t until the McIntosh family relocated to Los Angeles in 1937, following Robert’s acceptance into the Art Center School (now the Art Center College of Design), that McIntosh discovered his passion for three-dimensional objects. In LA, McIntosh acquired carving and molding skills while crafting hand-built frames at an art supply store. He also helped architect Richard Neutra in the construction of his parents’ home – a wise move, because not only did he learn about design, but also he could push for incorporating an art studio into the garage.

After a galvanizing visit to the Japanese ceramics and folk art pavilion at the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair, McIntosh used his new workspace to create his earliest works in clay. “In the garage I made a torso about 2 feet high and had it fired at a place called the Italian Terra Cotta Company, where they fired works up to 8 feet tall in very large kilns,” McIntosh says.

This and other early pieces were displayed at his first exhibition at the exclusive Bullock’s Wilshire department store in downtown LA. During this time McIntosh also took night classes at the University of Southern California, studying under pioneering ceramist Glen Lukens. Through these early experiences, he became good friends with potters Otto and Gertrud Natzler, whose works were also exhibited at Bullock’s. “Glen Lukens and the Natzlers were some of the few people who were making what you could call ‘decorative ceramics’ prior to World War II,” Mc-Intosh notes.

Lukens and the Natzlers were the first of many influential midcentury ceramists Mc-Intosh would encounter and befriend in the subsequent decades. When McIntosh returned from serving as a medic in World War II, he used the GI Bill to study ceramics at Scripps College. During this time, McIntosh learned about porcelain and the business of ceramics as an employee of Albert King; experienced the joy of spontaneous handthrowing in a workshop with Marguerite Wildenhain; took a seminar taught by legendary potter Bernard Leach; and met Shoji Hamada on his famous U.S. tour.

While these experiences, along with his friendships with Peter Voulkos, Paul Soldner, and Rupert Deese, his longtime studiomate, certainly influenced McIntosh, his work remained steadfastly his own throughout the course of his more than 60-year career. Timeless, minimalist, and flawless in form, his cosmic-inspired vessels and sculptures exude a strong sense of balance. “I think most people love Harrison’s work because the way he treats the surface and decoration inspires a sense of absolute peace, strength, and harmony,” says Marguerite, McIntosh’s wife, muse, and critic of 62 years.

Although McIntosh lost most of his eyesight more than 10 years ago, he still finds pleasure in sensory experience; he cites a recent visit to the James Turrell retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He has also continued a lifelong love affair with classical music.

Asked about his legacy and what he hopes the next generation will glean from his work, which is in museums all over the world, McIntosh replies, “Mostly, I hope people feel that my work has a serene quality.” In that sense, the objects mirror the creator.

Jessica Shaykett is the American Craft Council librarian.