Soaking in the Warmth

Bathing in a wooden tub can be both aesthetically pleasing and restful. Wood retains heat better than porcelain, allowing for a longer soak without adding hot water. The beauty and feel of wood can be grounding, too, and help us feel closer to nature.

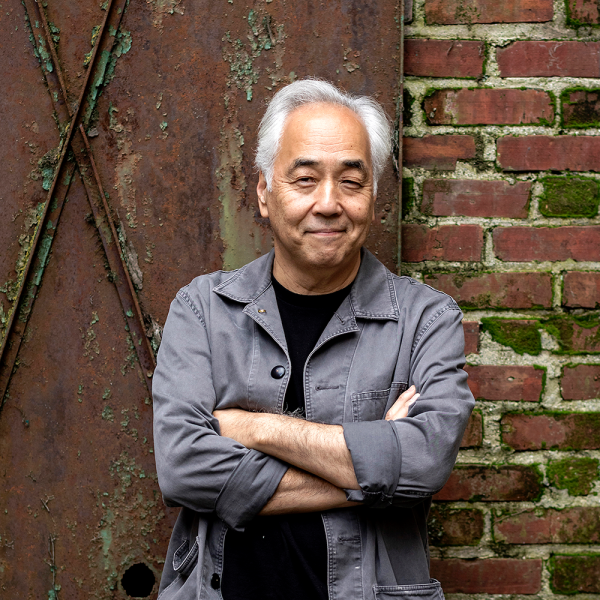

Port Townsend, Washington–based furniture designer and wood artist Seth Rolland’s Salish Sea bathtub has these qualities in abundance. It also embodies an experience of peace and pleasure that Rolland remembers with joy—“one of the favorite days of my life,” he says.

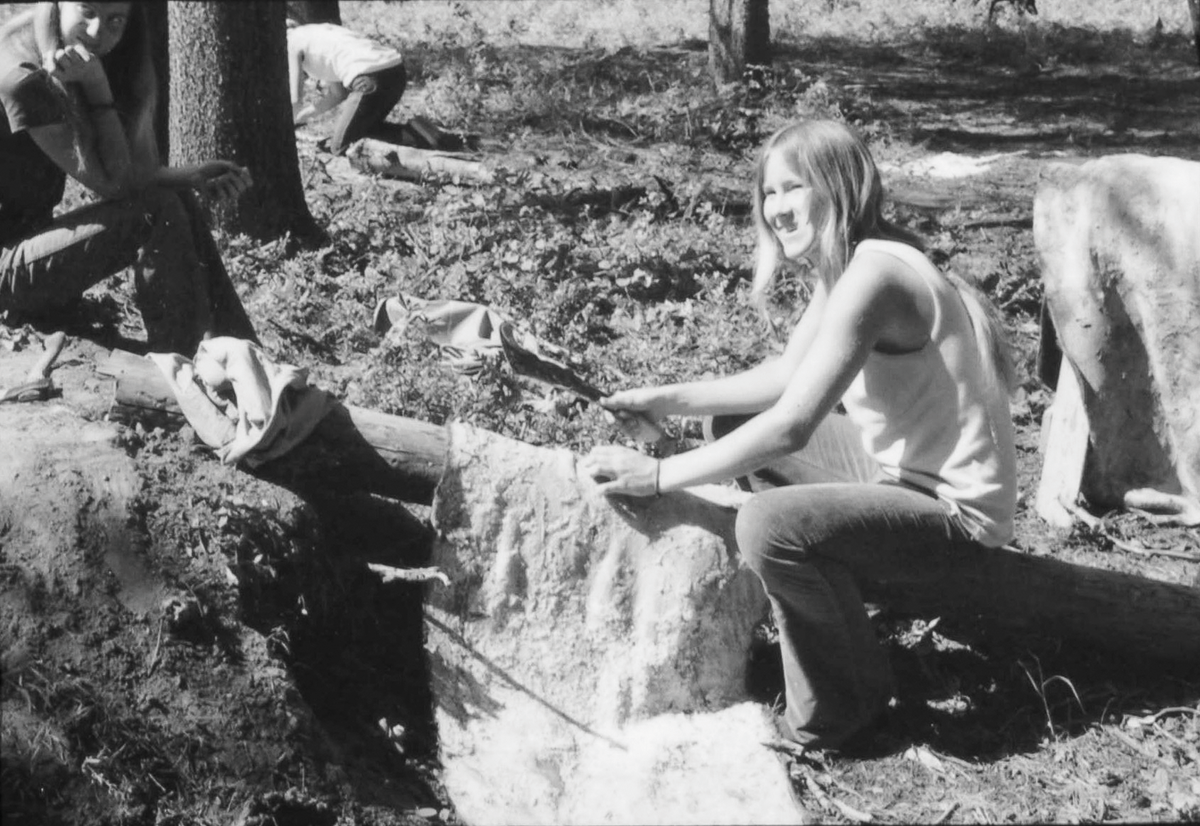

“One of my best friends built a sixteen-foot wooden dory, and he and I spent a few months driving it across the country, putting it in every bit of water we could. We got to Charleston, South Carolina, and sailed for five days between islands. We kept changing direction and the wind was always behind us. Going downwind is the nicest part of sailing.”

On that favorite day, which was particularly beautiful, Rolland lay low in the small boat, enjoying the view of sky and horizon beyond the graceful shape of the prow.

“This bathtub is very much that idea,” he says. “You’re immersed in warmth. You have this beautiful shape in front of you. I felt like I could put the best visual and physical aspects of sailing into a tub.”

While bathing in wood may be delightful, making a wooden tub is a real challenge because, as Rolland points out, “wood and water don’t mix. Especially wood and hot water. You have to create the reverse of a wooden boat; instead of keeping the water out, you’re keeping it in. My having done some boatbuilding made me feel like I could make it work.”

He made it work by putting together more than 200 pieces of durable sapele mahogany wood and sealing them with epoxy, then adding a fiberglass layer and six coats of varnish for internal “seaworthiness.” The tub’s sculptural energy and simplicity resonate with his other work—chairs, tables, and other pieces that combine a lively inventiveness with an organic, less-is-more aesthetic.

sethrolland.com | @seth_rolland_furniture