FLM Ceramics

FLM Ceramics

“One of the most important things to me in making my work is connection,” says Forrest Lesch-Middelton, who uses the universal language of clay to create everyday objects that touch us in an intuitive way, like a memory.

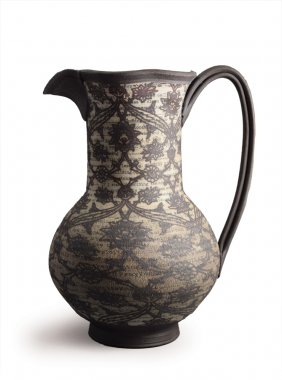

Handcrafted in his studio in Petaluma, California, Lesch-Middelton’s wares bear patterns inspired by historical pottery and textile motifs, mainly from the Middle East. He’s particularly interested in two bookending eras: the ancient Silk Road and the modern-day oil economy. Elegant florals and geometrics are screenprinted in rich, muted shades, from iron to cobalt blue. A reduction-cooling process gives the surfaces the weathered, timeworn look of ancient treasures dug up from an archaeological site. His work includes vessels and dinnerware, though tiles – launched a few years ago to offer smaller items at an affordable price – are the mainstay of the business.

“When I was a kid, we had this beautiful wooden coffee table,” recalls Lesch-Middelton, 44. “I would trace my finger over the scrolling patterns on it, and I always had my favorite spot.” Now he likes to imagine generations of families living with his tilework in their kitchens and bathrooms, in the pool or around the fireplace. “I love the idea of kids being playful, taking it in, over time finding the one tile that means something to them.”

Growing up in Seattle and Vermont, he was encouraged by his father, an architect, and mother, a psychologist, “to think beyond borders,” he says. “Keep your eyes open all the time,” they urged; “see the world around you.” In high school, he joined his friends in a pottery class and loved it, he remembers. “Up until then, I thought I was going to work on cars. Then my teacher said, ‘You know, you can go to college for pottery.’ I thought that was the funniest thing.”

He earned his BFA at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University in 1998. In 2001, he founded and ran a gallery in Berkeley, California, for a few years, then entered the MFA program in clay at Utah State University in 2003. The Iraq war had just begun, and besides the human toll, the damage included the looting of museums and destruction of mosques. He was moved by the loss of cultural heritage and “wanted to make work that spoke about it.” By the time he returned to California and established his practice in 2006, he was focused on honoring those decorative art traditions in a way that linked him to a lineage of ceramists across centuries and continents.

That sense of resonance is something he continues to cultivate in his craft. He collaborated with Iranian-born Arash Shirinbab, a multidisciplinary artist, on To Contain and Serve. Shirinbab, a calligrapher among other things, inscribed the body of work with proverbs, poetry, even tweets from people living in war zones in the Middle East – “what it means to have a homeland that you can no longer relate to,” Lesch-Middelton says. As a 2017 McKnight Fellow at Northern Clay Center in Minneapolis, he experimented with a Chladni plate, an acoustic device invented in the 1700s. “When you pour sand on it and stroke it with a violin bow, the sand reorients into patterns, depending on the frequency it’s tuned to,” Lesch-Middelton explains. His resulting Sound Wave tiles prompt unique reactions from viewers, he says, “almost like a Rorschach test. It’s all of this deeper meaning that we don’t necessarily even have to think about – we just feel it.”

Happily, his customers are feeling it, and business is brisk. The artist spends most of his time working with interior designers on tile projects for homes and restaurants around the country. He makes everything himself, with help from an assistant and from his girlfriend and creative partner, Beth Schaible, a bookbinder and letterpress artist. As if that weren’t enough, he recently opened a community clay studio in Petaluma and is writing a book on tile. The ceramist’s life, he says, “has just always been what I’ve done. It doesn’t feel like anything other than who I am. Which is kind of nice.”

A Pattern Emerges

Transference: Forrest Lesch-Middelton developed a technique called “volumetric image transfer” – screenprinting patterns onto wet pots on the wheel, while shaping them from the inside.

Omnivore: He applies design influences from not just Islamic art, but also seemingly disparate sources such as a South American hide rug (for a tile called Camino, Spanish for “road”) and a quilting pattern from Virginia (the Shenandoah tile).