Is the Future of Craft in Design?

Is the Future of Craft in Design?

It’s not realistic for most craftspeople to make a living working alone. That was the provocative argument made by Garth Clark, award-winning historian, writer, dealer, and auction specialist in ceramic art, at the conference of the Society of North American Goldsmiths in May. Clark urged craftspeople to emulate designers who partner with industry. We asked him to elaborate.

You’ve said “the crafts are a threatened field,” suggesting that purely handmade work can’t compete with more scalable, cost-efficient work. What is threatening craft now? The big weakness is a failing economic studio model. Overheads rise constantly, but each maker has only two hands and can’t make more work to bring in more money. There is an output ceiling. This threat is self-imposed, coming from adherence to a medieval concept of craft and refusal to employ low-key industrial techniques to produce more inventory. Another threat: Craft galleries are withering and in some cases closing. Then, of course, there is the damage to the brand of craft done when institutions such as the flagship American Craft Museum [predecessor to the Museum of Arts and Design], drop the term craft and seek to join the fine arts world.

Let’s get specific: Discussing jewelry makers, you’ve said there is a disconnect between what some are making and what is selling – that a lot of emerging artists’ work is too sophisticated for the general market. Why is that? And can you cite examples? Though fairly ordinary jewelry sells well, exceptional, costly pieces – those on the cutting edge – do not have the sales platform that existed in the 1980s and ’90s that would allow artists to live by their work. This casts our avant-garde in a purely academic role.

Lauren Kalman and Jennifer Trask are good examples of jewelry artists whose work is not widely marketable as craft. There are others in whose work concept trumps materials. The market for this kind of expression is minuscule – maybe a dozen galleries worldwide. A better venue for artists like Kalman and Trask is the more adventurous end of the design world, sometimes called applied art.

As you’ve suggested, for a number of years craftspeople aimed to be accepted in the fine art world, with limited success. Your view is that, in general, the design world is a more promising avenue for craftspeople. Why? Most crafters are not fine artists, even when they use fine art as their muse. The ones who have crossed over are about .0001 of the craft community. It’s a tiny handful: Ken Price, Josiah McElheny, Betty Woodman. The odds are hardly encouraging. On the other hand, designers and crafters do exactly the same thing; they make vases, jewelry, furniture, mugs, hats, fire irons. It’s exactly the same class of objects. Both are designed. The difference is the means of production: Crafters work by hand, while designers employ industry. Designers have learned to have it all – some unique works, some limited works, and some mass-produced works. Crafters can do the same.And the market is gigantic and growing.

How do we know that craftspeople will be accepted as designers? There is not a border guard for design the way there is for the fine arts. Fine art is an artificial market, kept alive not by the intrinsic worth of the art – there is none – but by the aura of glamour and privilege and genius. Entry is carefully monitored. On the other hand, anyone with design talent can enter design. If you have talent, you are in. Becoming successful is another matter, of course. You’ll need hard work and the occasional stroke of luck. There is lots of competition, some of it brilliant.

Craft’s Achilles’ heel is aesthetic. Most of the craft I see is too dull and old-fashioned to compete in the design arena. Overall, design tends to be more innovative, even creating its own materials and manufacturing processes when needed. For whatever reason – aging faculty in craft programs? – much of craft is not current with today’s visual sensibilities.

Let’s talk history. The field of modern craft, like the field of modern design, emerged as something of a reaction to cookie-cutter industrialization. Where did the two part ways, and what can craft learn from design? Craft and design are twins separated at birth. They share ancestry: the mid-18th-century reform movement. One group decided to fight the ugliness of industrial products from within (modern design) and the other from without (modern craft). Even a hundred years ago it was clear which of the two would triumph. Given that, what can craft learn from design? Live in the now; do not create work that relies on the rustic sentimentality of ye olde crafter. That is tired and – literally – so yesterday. Make fresh, vital visual objects that are culturally relevant in the moment in which you are living.

Does design have anything to learn from craft? Yes. One cannot beat the intimate understanding of material, process, and form that comes from a craft education. All designers should go through a few years of hands-on material training. It would make them better designers.

If fewer people work with their hands to produce craft, won’t that represent a kind of cultural loss? Or do you think only craft insiders will care? If every crafter disappeared tomorrow, the impact would barely be felt. Yes, our community would notice, but the average citizen would not. Fine art would not change, and design would move forward without breaking stride. But I am not advocating artists in the crafts leave the field entirely for design. I suggest a hybrid, making use of both worlds, including the design marketplace.

The Dutch call unique craft objects “free design,” meaning that they are released from the machine, at least to a degree. (A wheel, after all, is a machine. Craft is by no means completely pure.) There is a place for craft in the design world, but, again, it’s got to be contemporary and stylish. Consumer tastes are much more sophisticated today.

Craft education tends to be focused on one material or another – metals or clay, for example. Does that sort of education still serve artists coming out of schools? Or should craft education merge with design education? Two things can help craft education. One is for schools to offer different paths. In Copenhagen, one can go to the Royal Academy and make art. Or one can go to the [academy’s] design school and head in that direction. At Norway’s art academy in Bergen, ceramic students use their material in a way that leads directly to fine art. Ceramics as a medium-specific discipline or profession is not taught.

Merging with design courses would be great. And I would, alas, also suggest a name change. The craft departments can become “material studies,” a title with sturdy Bauhaus roots. They can provide hands-on experience to art students in a world gone virtual.

And it’s not only educational institutions that need to change. Craft organizations need to start building bridges to the design world and sharing resources. Re-member the designer-craftsman groups of the 1930s? Their time has come again.

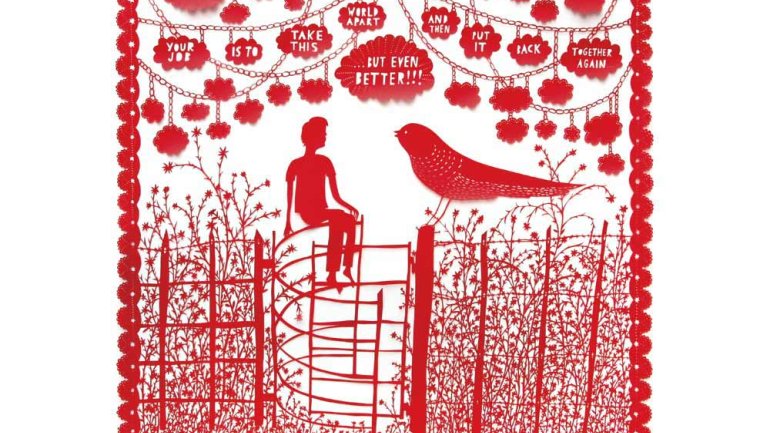

What advice would you offer today’s aspiring craftsperson? Decide what you want to be – be it fine artist, designer, or for that matter, crafter. And live there. If you believe you are, say, a sculptor and not a crafter, then the day you leave college, take the strengths of your craft education and head to a sculpture community and make your home there. Don’t remain in the relatively protected world of the crafts and whine that you are a misunderstood artist trapped in the craft world. Leave the nest, and learn to fly.

You can read about craftspeople making it in the design world in our upcoming December/January 2013 issue. Monica Moses is American Craft’s editor in chief.