As I inhabit the studio, I often consider differences between what we call art and design. Design emerges as a combination of intuition and function, whereas great art can emerge incredibly from trusted intuition alone. However, if one considers that both art and design carry a spiritual function, we begin to move into the creative space occupied by Indigenous societies and cultures around the world—a creativity that is aligned with nature and carries, by extension, the freedom to express one’s essential nature.

I have always inhabited the mental space that views art and architecture as a single entity. It could be my roots talking. West African Yoruba culture has for millennia established a highly developed cosmology and social architecture, which is not overtly apparent from its physical architecture. Perhaps this is why I find it so important to pull elements from one discipline to inform the other. Internally, I am always engaged in cross-disciplinary conversations in the studio.

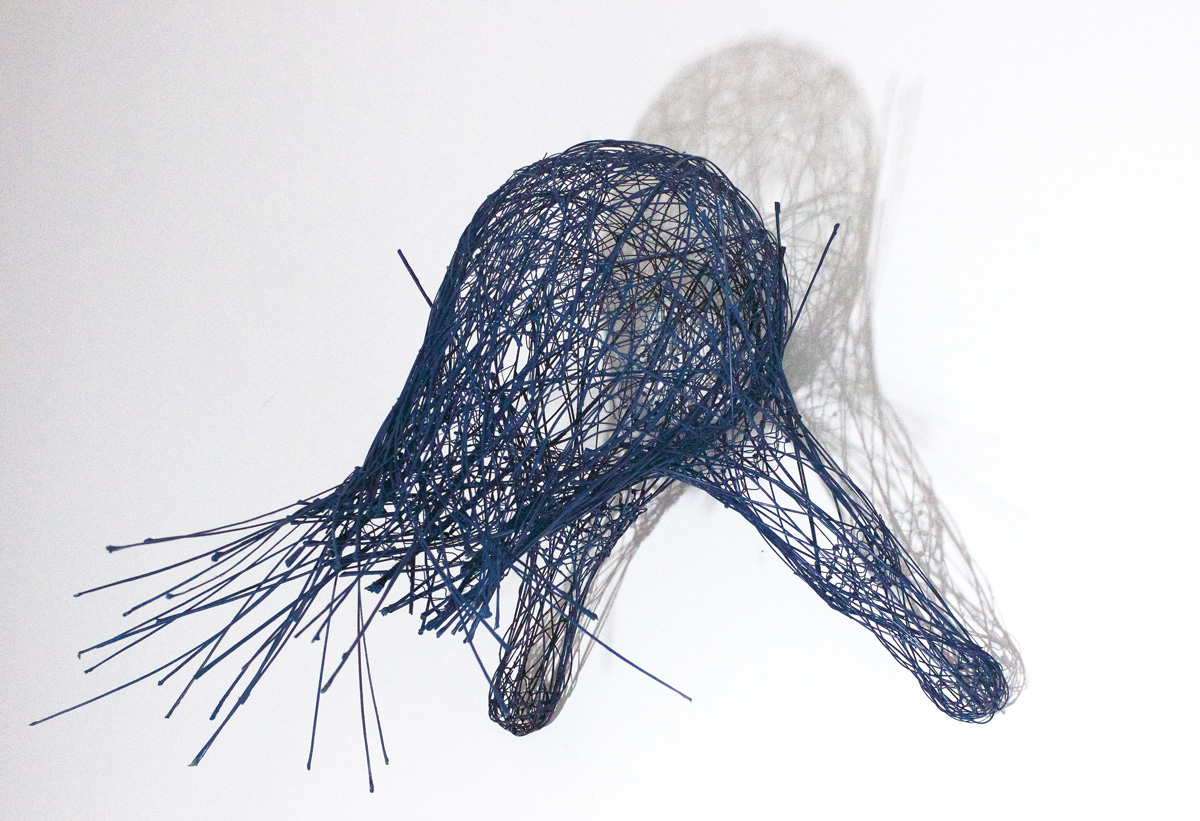

However, the processes of both are very different. With the exception of some mixed-media works on canvas, which I have formed as sculptural reliefs from drawings, I do not produce any working drawings in my art practice, as I do with architecture. Certainly, never for the sculptures. It is pure intuition pouring forth.

When I look back at artworks I’ve created over the years, I always find threads that speak to architecture. Similarly, now that I am reengaging with architecture, my artistic background shines through very clearly.

Within my multidisciplinary practice, I explore hybridity in terms of balancing masculine and feminine energy, or sexuality, but also when it comes to duality with my materials. Merging natural and industrial forms, I draw inspiration from Yoruba spirituality and cosmology as it flows with universal links that also seek to bridge and weave African, African American, and diaspora concerns.

My architectural design, Visible/Invisible, is informed by a sacred symbol of interlocking links within Yoruba culture. To help the understanding of those not familiar, I call it an “African Yin-Yang,” through which I invite visitors and audiences to seek reconciliation within themselves. I encourage them to ask deeper questions, such as, “What is your destiny or purpose?” Essentially, it’s about developing a worldview or deeper sense of the environment that permeates all aspects of life.

Adejoke Aderonke Tugbiyele in her former studio at Project for Empty Space in Newark, New Jersey. On the back wall, top, is Tugbiyele’s The Road to Divinity, 2021, from the series Royal Blood.