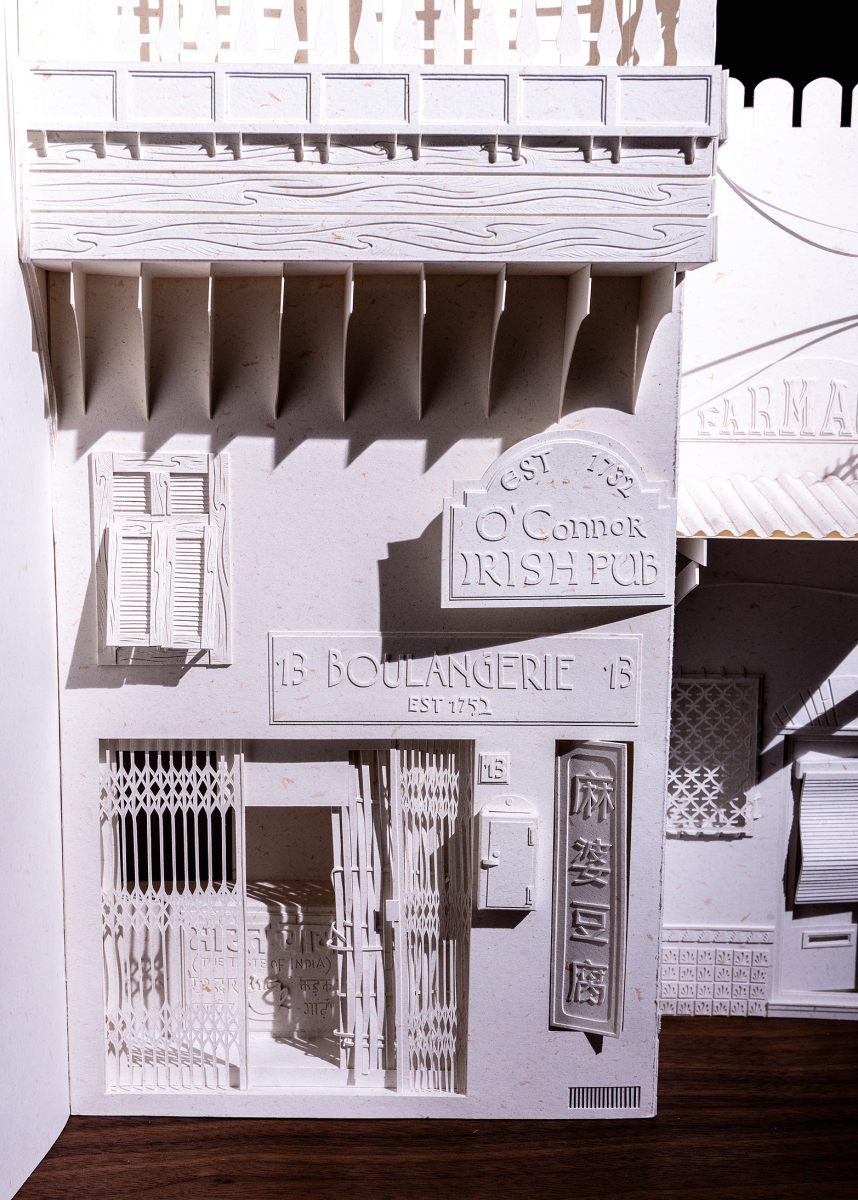

Konjiki no No, 2022 (pictured above)

AYUMI SHIBATA

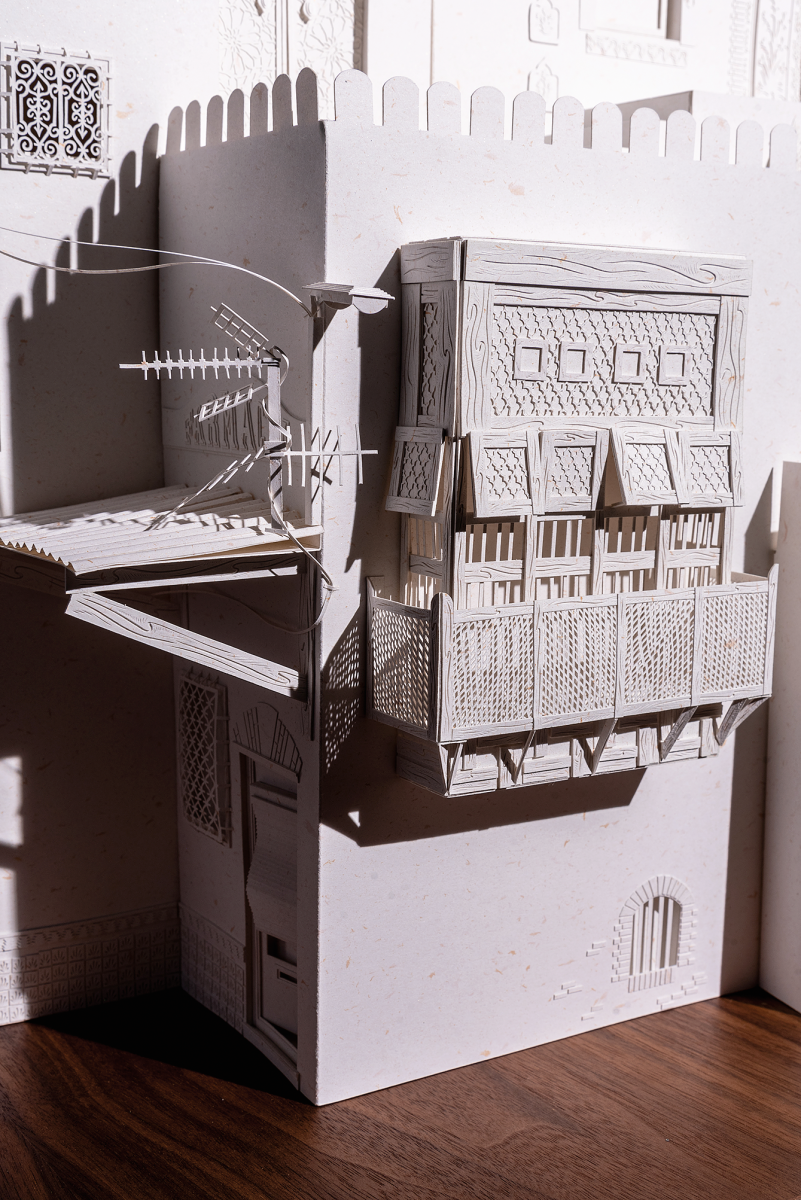

It’s called Konjiki no No, Japanese for “the golden fields”—a glass case through which light is shone from behind and below, in a darkened environment, to gild a land-and-townscape made entirely of cut paper.

The fusion of nature, human habitations, and something like a temple in the piece’s imagery sums up the passionate idealism of Ayumi Shibata. “The theme of my work,” she says, “is to create a sustainable, harmonious world. I put into my artwork a vision of hope for the future—for example, an ideal city or a forest where animals, humans, and nature coexist.” Shibata’s oeuvre contains many such visionary marriages of glass, layers of cut paper, and light, as well as other cut-paper works, large and small.

Born and based in Japan, Shibata lived in New York from 2012 to 2015, and it was there that she discovered her vocation. One day, after meditating in a quiet church in the hectic city, she opened her eyes and saw “seven-colored light spreading through stained glass all around my feet and the floor. The beauty of it shook me to my core. At the same time, I recalled how much I loved arts and crafts in school, especially cutting black paper and pasting colored cellophane to make something that looked like stained glass.

After some years of cutting paper as a hobby, she turned professional in 2020 and since then has contributed to international exhibitions as well as to haute couture shows and the stage sets of Japanese folk music icon Ryoko Moriyama.

She’s developed a genuinely religious devotion to paper, pointing out that the Japanese word for it, kami, is a homophone for kami, the country’s ancient deities. She celebrates the spiritual power of light too. “Life can’t be nurtured without the light of the sun,” she says. “We’re alive in the hands of the Great Love.”

Shibata works on a new piece, Cyouwanomori, which translates from Japanese to “forest of harmony.”