In Our Studio: Studio Alluvium

In Our Studio: Studio Alluvium

Ceramists Mitch Iburg (left) and Zoë Powell (right) at work in their studio in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Photo by Zoë Powell.

LEFT: This piece from Zoë Powell’s Silk series (2020) was made with a Minnesota clay blend fired to 2,250˚F in an electric kiln. Photo by Zoë Powell. RIGHT: Mitch Iburg’s finished vessels (2020) were made with foraged Minnesota clays and minerals and they were fired to 2,200˚F, also in an electric kiln. Photo by Mitch Iburg.

We chose the name Studio Alluvium because of how the term alluvium relates to our philosophy toward collecting and using local materials. Alluvium is a geologic term used to describe sediments—silt, sand, clay, or gravel—that have been eroded, transported from their original source, and deposited in a new location by water. Just as the surficial geology of the Twin Cities region consists of deposits transported by glaciers and rivers, Studio Alluvium functions as a place where clays and minerals from all regions of Minnesota are brought together.

It’s not only a place of work, but also a meeting place of histories, materials, and ideas. We work nearly every day, so it’s important to us that the space is welcoming and functions as an extension of our home.

Iburg and Powell collect clays from many regions of Minnesota. Here, Iburg brings clay into the studio. Photo by Zoë Powell.

A Day in the Studio

Following a short commute through the city’s residential streets, we arrive at the studio building, centrally located between Minneapolis and Saint Paul in the historic Midway neighborhood. Originally constructed as an industrial canning facility in the early 1900s, this building is now home to many artists and creative entrepreneurs.

We were first attracted to this space because of its many textures: worn concrete, exposed brick, rustic timber. The patinas of these surfaces act as reminders that we are contributing to the history of the space, not only by extending its usefulness, but by finding inspiration in and honoring its aesthetic.

As we descend the stairs to the basement level, sounds from the world outside become muted. Entering our suite, we are met with stillness. A wall of large windows illuminates the varied surfaces of our working area with a clarifying light. Knowing this tranquility is fleeting, we spend the first few moments of each day enjoying it before beginning the day’s work.

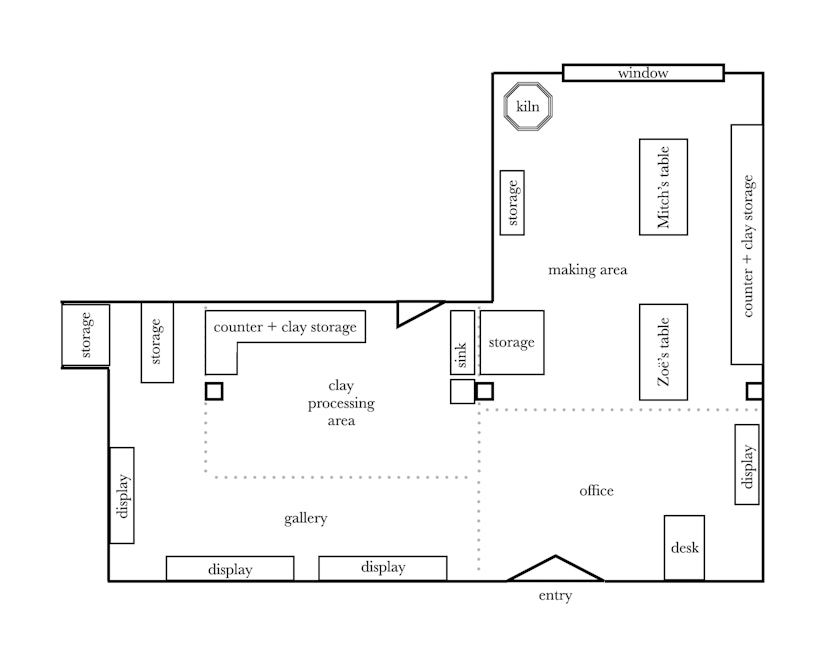

A floor plan shows how the studio is divided into four zones: clay processing area, making area, office, and gallery. Floor plan courtesy of Studio Alluvium.

No two workdays are ever the same. A single day may involve screening 50 gallons of clay slurry, constructing several hand-built pieces, developing clay body or glaze tests, and organizing inventory. Others may be spent entirely behind the camera documenting work.

The diverse range of tasks has taught us that operating a studio is just as much about managing the space as it is about making work. Studio Alluvium is an open 1,100 square feet with designated areas for storing and preparing raw materials, making and firing work, storing finished inventory, and packing and shipping orders.

Over time, we’ve come to understand the rhythm of our studio as one does the changing of the seasons. Throughout the year we each fluctuate between different projects, and we value having a workspace that allows us the flexibility to produce everything from large sculptures to tableware commissions. Alternating between multiple projects keeps us inspired and helps financially support the studio.

While we collaborate through material sourcing and testing, we have distinct bodies of work which we pursue independently. Despite these individual pursuits, we always work side by side. There is a sense of comfort and respect in our relationship that allows us to occupy the same space without impinging on each other’s artistic development. Our close proximity allows us to discuss ideas openly, without resentment or competition.

A central idea in both of our practices is that different expressions require different materials, and vice versa. Sometimes our use of a material is defined by a vision for utility; other times it is defined by the material’s intrinsic properties. Although we work separately, and in different ways, this philosophy is something that holds true for both of us.

Materials and Innovations

Over the past four years, we’ve become more ambitious in using local resources exclusively. Pursuing this goal in an urban studio has presented us with many challenges requiring creative solutions.

Each summer and fall we collect approximately 3,000 pounds of raw material—enough to last us through winter and spring, when the climate makes the landscape unfavorable for harvesting. The need for year-round access to large quantities of material forces us to use our limited space efficiently. Most of our clays, sands, and stones are stored in roll-out bins beneath countertops and tables, thereby maximizing our storage capacity.

The office area provides a clean space to greet visitors and break from the day’s tasks. Photo by Mitch Iburg.

Many of our resources contain organic matter and problematic mineral impurities that must be removed during preparation. In the city we are more mindful of how we handle our clay waste, as we cannot easily return these materials to their source. Rather than sending our screenings to a landfill, we use them in alternative applications, like glazes or grog.

All of our work is fired to cone 6 in an electric kiln. Given that only a fraction of our electricity is powered by carbon-free sources, we recognize the impact our firings have on the environment. To reduce our carbon footprint we have formulated all our recipes for once-firing. However, because many of the resources we use are fine-grained and high in organic matter, our clay bodies require custom firing cycles to avoid various problems. We rigorously test our materials to understand how and when these problems occur in order to maximize efficiency.

Fostering Community

One of the most rewarding aspects of our process is sharing our approaches to testing natural resources. We teach several workshops a year, both from our studio and at art centers around the country. In light of recent travel restrictions, we have transitioned to an online teaching model, allowing us to interact with a global audience of makers investigating their own materials.

Although temporarily interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, we usually host two open-studio weekends a year for our local community to see recent work and learn about the resources we use. Many visitors have a close connection with the same regions where we collect materials. For them, seeing this work is a reminder of place and home. For us, hearing their stories reaffirms our belief that material can function as a powerful vessel for history and memory.

studioalluvium.com | @studio.alluvium

Mitch Iburg is a ceramic artist who works extensively with clays, rocks, and minerals collected directly from the landscape. He received his BA in fine arts from Coe College in 2011 and has since worked at studios in Virginia, New York, California, Denmark, and Estonia.

mitchiburg.com | @mitchiburgceramics

Zoë Powell graduated from the College of William & Mary in 2016 with a BA in fine arts and a BS in biology. Her work consists of organic sculptural vessels made from clays and minerals she collects and processes herself. She is interested in the idea of transitional spaces and how certain forms can evoke a sense of comfort to an otherwise vulnerable viewer.

zoepowellceramics.com | @zoepowellceramics

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.