Owning It

Owning It

Tiff Massey, here in front of a section of Detroit’s skyline, wears jewelry she designed and made by hand, including a necklace with her signature form: the coil. Photo courtesy of the artist.

As she’s watched her city gentrify at the hands of opportunistic developers and outsiders, Massey has nurtured a creative practice that keeps this culture at its heart. A classically trained metalsmith, she makes jewelry as well as large-scale steel and brass sculptures that adorn entire rooms. She is heavily influenced by 1980s hip-hop and bling and has put her own spin on four-finger rings, supersized dookie rope chains, and door-knocker earrings. One of her signature forms is the simple coil, which she often uses as a building block to play with shape and dimension.

Gigantic ring sculptures are part of Everyday Arsenal (Bling Edition), an installation in Say It Loud, Massey’s 2018 solo exhibition at Detroit’s Library Street Collective gallery. Photo courtesy of the artist

Wearable or not, the resulting pieces are meant to embody the unapologetic energy of flaunting. “Jewelry isn’t jewelry until it’s activated by a body,” Massey says. “When people do put on my pieces, the scale and weight changes how they present themselves. The shoulders get broader. They’re feelin’ themselves.”

Massey has spent much of her pandemic year preparing for a busy summer. A solo exhibition of recent and new work opened in July at the Metal Museum in Memphis, Tennessee; an expanded iteration will travel to Michigan’s Muskegon Museum of Art in November. One highlight of the all-metal display will be an immersive installation of colossal brass and steel rings surrounded by mirrors—a gleaming jewelry box that people can walk through while becoming one with the work. Massey presented an earlier version at Detroit’s Library Street Collective gallery as part of her 2018 solo show, Say It Loud, but the forthcoming exhibitions offer a welcome challenge to take over even larger environments.

“I like to utilize scale for people to interact with my wearables in a different way,” she says. One of her dream projects is to create Detroit’s public art equivalent of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago. Massey’s tentative design, which won her a Knight Arts Challenge grant in 2017, is a monumental coil bracelet that people can walk through—jewelry as architecture. “If I make this bracelet at 40 feet by 20 feet, who’s wearing who at that point?” she offers.

Massey wears Everyday Arsenal, a four-finger ring she made for herself. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“When people do put on my pieces, the scale and weight changes how they present themselves. The shoulders get broader. They’re feelin’ themselves.”

—Tiff Massey

In continuously sizing up, Massey purposefully takes up space in more ways than one. She is asserting her voice as a Black Detroiter in a long-standing arts scene that many newcomers and visitors fawn over as hot and up-and-coming. She is also making highly visible certain threads of Black culture that gentrification displaces, whitewashes, or erases. “It’s really me being nostalgic about a Detroit that probably won’t exist again,” she says of her approach.

Born in 1982, Massey has never relocated from Detroit. She grew up in the northwest neighborhood of Bagley, in a family that deeply valued personal luxury. Motorcycles, new cars, and fur coats are among the memorable objects from her childhood. She also remembers accompanying her father to jewelry shops where he ordered custom pieces, including chunky, colorful Lucite rings she would replicate, years later, in metal. “It’s all embedded in the idea of the stunt,” she says of this lifestyle. “It’s like, things people think rich people do that they don’t.”

Massey studied biology at Eastern Michigan University, but she also took jewelry courses. Wanting to pursue art, she later enrolled in the metalsmithing department at the prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Art. She began thinking more intentionally about scale and the performative nature of jewelry, but also how the act of adornment can represent something more insidious. “I knew I wanted to make work that talks about how white folks appropriate Black culture but don’t want to have shit to do with Black people,” she says. “So much money is being made off of Black culture that is not being seen in Black spaces.”

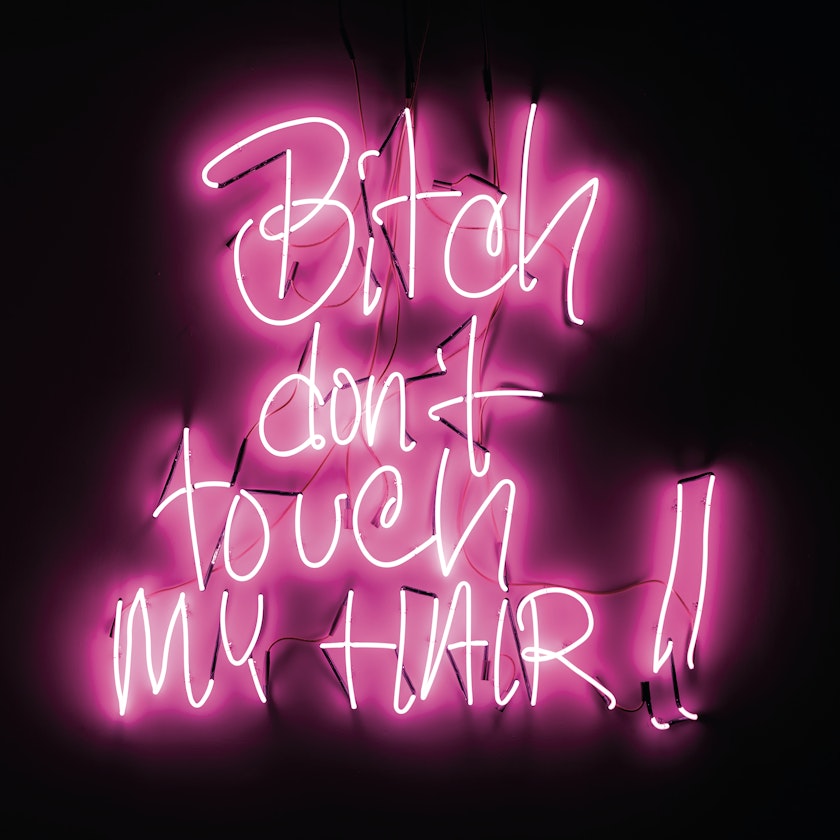

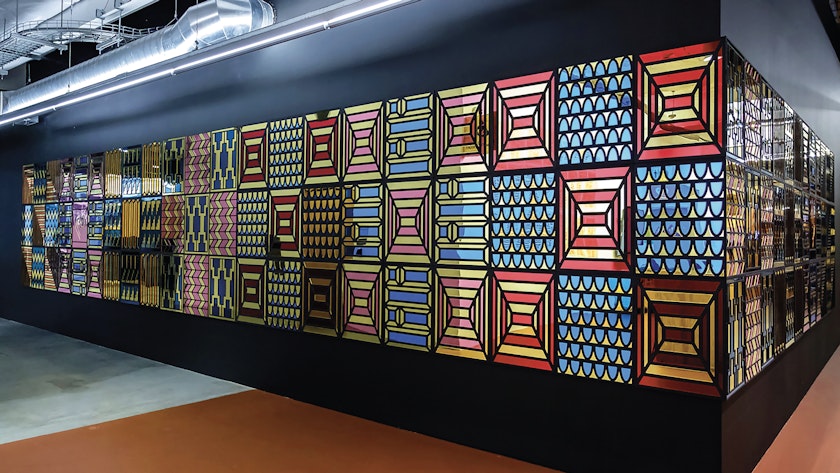

RIGHT: Massey’s first neon sculpture is a 5 x 5 ft. warning that she calls a self-portrait. BELOW: Quilt Code III: 99 Problems weds wood and acrylic images from traditional craft and high tech. It was commissioned by Facebook for its global headquarters in Menlo Park, California.

One series from 2011, titled They Wanna Sing My Song But They Don’t Wanna Live It, consists of extravagant chains Massey made out of steel and softer materials such as gold leaf and wool. She draped the necklaces on white models and photographed them in the style of fashion editorials. When she graduated later that year, she was the first Black woman to receive an MFA from the metal-smithing department.

Massey has since received numerous accolades, from Art Jewelry Forum’s Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant in 2019 to a United States Artists Fellowship this February. Often labeled as craft, her practice has rarely been one-note. Metal is a core material for her, and she handles most of the manual labor herself, wielding hammers and fire to form, bend, solder, and weld her visions into life. She has also created wallpaper, textile collages, and wooden sculptures, including a series of supersized barrettes based on the plastic snap accessories that many Black girls use to style their hair.

Massey, who was awarded a 2021 United States Artists Fellowship in Craft, wears jewelry she designed and created. Photo by Joe Gall.

“I’m all about flourishing. I’m really trying to see how big I can make this practice, how many people I can help along the way, and how I can impact my community.”

—Tiff Massey

What Massey is establishing is a body of work that upholds pleasure as a form of self-empowerment and resilience. More than ornaments, her jewels are totems of identity and belonging. These themes also drive what is shaping up to be the biggest project of her life: the development of an art school in Bagley that will serve its direct community.

In 2017, Massey purchased a former bowling alley with the intention of transforming it into a nonprofit institution modeled on Cranbrook’s pedagogy. Named Blackbrook, the school is her solution to address a scarcity of opportunities and resources for Black youth. “I’m developing it according to what is needed—not what my pocket needs,” she says.

Massey stands beside the former bowling alley she owns on Detroit’s West Side. The Cranbrook-trained artist is turning the building into Blackbrook, an art school for Black youth. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The plan received a Kresge grant last August, and Massey has been busy developing next steps. Still, the global shutdown has largely forced her to slow down and figure out how to direct her energies. She is experimenting with brass and has ambitions to use chasing and repoussé to make metal quilts. She wants to realize more public artworks, including Get Big, an interactive environment whose proposal won her the Susan Beech grant. And on the business side, she dreams of launching a design firm dedicated to Black luxury. “I’m all about flourishing. I’m really trying to see how big I can make this practice, how many people I can help along the way, and how I can impact my community,” she says. “I have grand, expensive ideas, let’s just say.”

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.