Continuity and Change

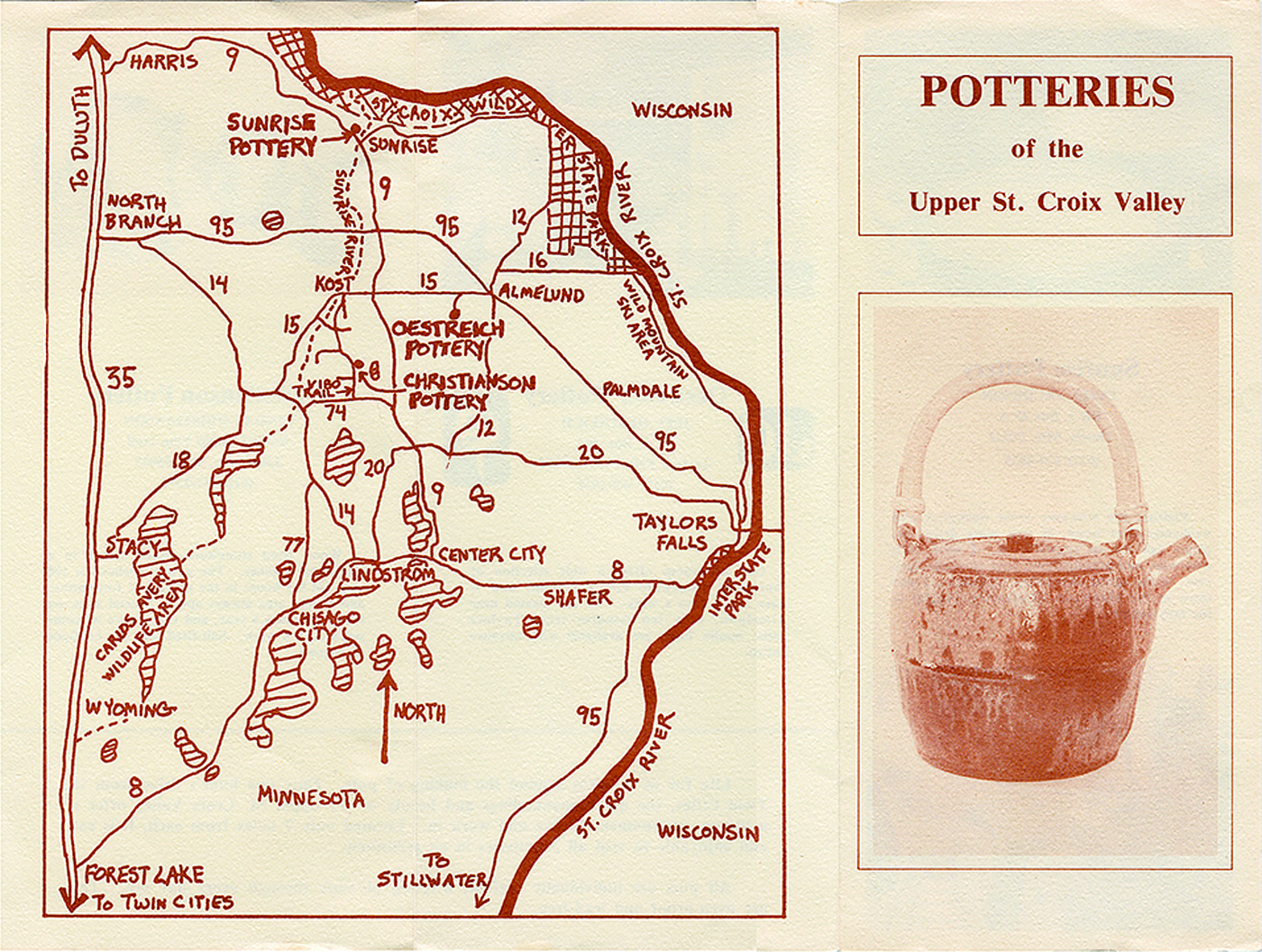

The tour originated when Oestreich, Christianson, and Jacobson all moved to the upper St. Croix River Valley around the same time and decided to hold simultaneous sales, with a brochure and map, in hopes of drawing bigger crowds. The coordination expanded after Swanson joined Jacobson and Bob Briscoe built a house and studio nearby. Briscoe is credited with being the promotional energy behind the tour. “He brought in a spirit of marketing that we didn’t have before, a kind of can-do attitude, which not everybody has,” Swanson remembers.

Briscoe, Oestreich, and Christianson have been major figures on the workshop circuit, where they would take the opportunity to hand out flyers for the tour as it grew. For the first three years, MacKenzie participated, which attracted many people, and then he bowed out. There has been a slight change in membership over the years, most strikingly in 2016, when Briscoe sold his house and studio to Krousey, and Connee Mayeron Cowles passed her site to Kasten. Briscoe has since retired from pottery making, but Mayeron Cowles still participates in the tour at her former studio.

The generational shift was acknowledged last year in a different way at Cuellar’s studio, where his daughter, Alana Cuellar, showed her work in person after participating in the virtual event during the pandemic years. In 2023 she will be his cohost, and eventually, he says, she will be the host and he a guest. A generational focus is also planned by Oestreich. He intends that in 2023 the majority of his guest potters will be under 40, to encourage the legacy of function. In 2022, exceptionally, his selection of guest potters had a local focus. He invited Leila Denecke, Ursula Hargens, Ernest Miller, and Nate Saunders from Minnesota; Jim Grittner from Wisconsin; and Margaret Bohls, now in Nebraska but formerly of Minnesota. In a show of loyalty, he included the Leach Pottery of the United Kingdom, where he apprenticed from 1969 to 1971.

This year marks one more major change: the addition of an eighth studio on the tour, that of Peter Jadoonath. A guest exhibitor since 2018, Jadoonath is currently co–board president (with Lindsay Oesterritter) of Studio Potter online magazine.

There is some debate over whether the St. Croix Valley tour or 16 Hands, in Floyd, Virginia, is the oldest continuously operating American pottery tour. But the Minnesota version has certainly grown larger and become more influential. Its advantage over 16 Hands is being located within an hour’s drive of a metropolitan area of nearly four million people. Its annual choice of Mother’s Day weekend is strategic: Minnesotans and Wisconsinites are usually by May desperate to get out after the long winter, and usually the weather is reasonable. But not always. I remember that about 10 years ago the tour weekend was rainy and gloomy. I thought, What a shame, probably no one will come. I was quite wrong. The crowds were as good as usual, and everyone laughed about the mud on their boots, pants, and cars. Most of the sites have both tents and some indoor space, but even at unprotected tables, such as at Cuellar’s, pottery is not going to be hurt by a little rain!

The St. Croix Valley Pottery Tour has been the model for other locations, such as Art of the Pot in Austin, Texas, which follows the Mother’s Day timing and the practice of inviting guests. However, the underlying appeal of every pottery tour is visiting studios and getting a hint of how potters live.

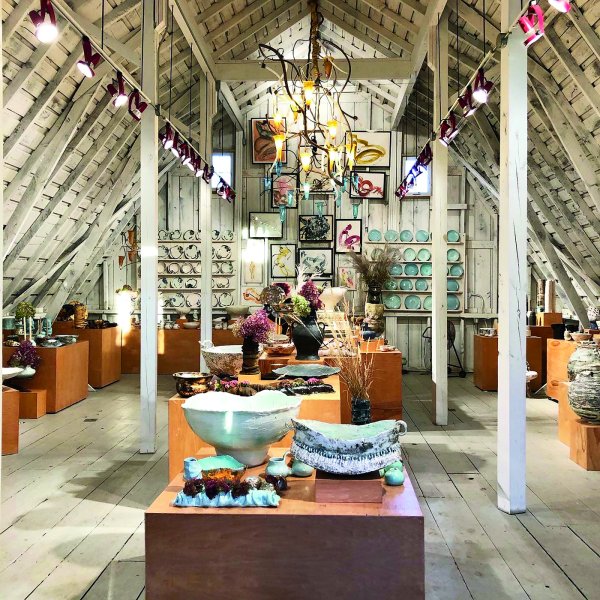

“The potter has to be there,” says Swanson, who has taken on most of the organizational responsibility for the St. Croix tour. “The whole idea is to go and meet the potters, see three hundred of their pots, so it’s really a different experience from going to a gallery and seeing eight or ten pots and having some employee of the gallery explain it to you. There are still lots of people who walk in the door and say, ‘Oh, I’d like to live in the country and make pottery.’ There’s that vicarious thing of how do these people live, how do they do this?”

Oestreich says, “You know, what I like about it is it’s returning to what potters did a thousand years; they sold right from their studio. And I love that. We need galleries, too, though. We need it all, internet, gallery sales, home sales, tours; we need it all to reach the public.”