Sacred Harvest

Sacred Harvest

Pat Kruse has a deep and reverent connection to the natural world, which he honors by making beautiful, expressive objects out of the birch bark he gathers in forests near his central Minnesota home.

“I’m just a birch-barker – not too much more to it than that,” says the artist, 45, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Ojibwe. “I’m dedicated to what I do, and I love to do what I do.”

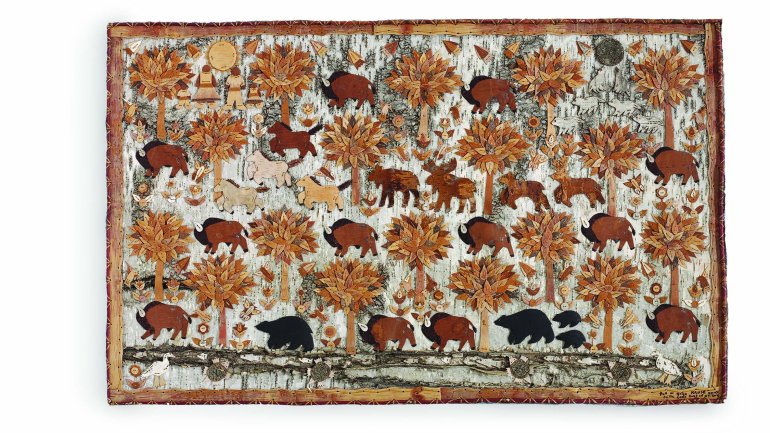

In collaboration with his 21-year-old son, Gage, Kruse creates intricate “paintings” and baskets out of bark pieces sewn together with deer sinew. Some of his designs are abstract, while others depict images from nature, such as flowers, turtles, bears, and butterflies. He gets his rich, nuanced range of earth tones from different birch species – white, gray, yellow, silver – as well as from second-growth and even dead bark.

At the heart of Kruse’s art is love for his material, a passion that stems from his heritage. “Ojibwes have always known that birch bark is a sacred thing,” he says. “The skin of a tree is also a house, a boat, a drinking cup, a bowl, a storage container – then come all the different kinds of art. Birch bark is so sacred that we try not to waste even a scrap.” It’s this authenticity that lends a special soul to his pieces, which are prized by collectors.

“As a traditional cultural artist, Pat is the embodiment of gratitude and respect. If you’re lucky enough to get a chance to speak with him, you begin to understand how grateful he is to carry forward the birch-bark art forms of his cultural predecessors,” says Benjamin Gessner of the Minnesota Historical Society, where Kruse spent six months as an artist in residence, studying 19th- and early 20th-century Ojibwe birch-bark artifacts in the collection. Gessner adds, “As Pat once explained it to me, the ancestors are communicating with us through what they have physically left. In these items, he sees worlds of possibilities for teaching and learning.”

“My mom told me I was born to be a birch-barker,” says Kruse, who grew up on the Mille Lacs and Leech Lake reservations. As a boy, he was always making “little things” – beaded objects, Christmas ornaments, dream catchers – but was most drawn to birch-bark crafts, which he learned at the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig tribal school and by watching people in his community build traditional birchwood canoes.

“My uncles and my mom and all, they were blanket makers and beadworkers and birch-barkers,” Kruse explains. “We picked wild rice, onions, sweetgrass, wintergreen. My family lived off the forest, because there wasn’t much opportunity for employment on the reservations back then, and even to this day.”

In his late teens and early 20s, he did a stint as a union worker in Washington state, maintaining naval ships. When he returned to the reservation and became a father, “I had to do something to make money, so birch bark it was.” He produced unadorned objects at first, until his mother encouraged him to pursue a more decorative “old-school” Ojibwe style: “Once I started doing that, my whole life changed.” Before long, his work was not only selling briskly at the Mille Lacs trading post, but also gaining broader attention in galleries and museums.

Now Kruse and son spend their summers harvesting bark, then settle in during the winter months to make art. He’s proud to have Gage by his side, carrying the craft on to a new generation. “It’s like, my hand and his hand, same thing.”