Passover is an eight-day Jewish celebration of the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt during the 13th century BCE. Its centerpiece is a meal called the seder, which usually takes place on the first night. Participants gather then to tell the story as outlined in the Haggadah, an ancient Jewish text.

When I was a boy, our family Passover tradition involved a trek from Dayton, Ohio (and later Arlington, Virginia), to my grandparents’ home in Youngstown, Ohio, where my parents and I would join my father’s siblings and their families for the seder. The kids, who only got to see each other once a year, would run around and entertain themselves with games. The men would complain about the Cleveland Indians while playing pinochle. And as the festivities unfolded, my Zede (grandfather) and Bubba (grandmother) would rule their respective turfs with an iron hand.

The seder itself started at sundown and seemingly lasted forever. It was all in Hebrew and involved a reading of the Exodus story, as well as commentaries from ancient sages, and a tradition during which the youngest person present asks The Four Questions, a rhetorical device to prompt a discussion about what made this night different from any other.

The seder plate is at the center of the evening from beginning to end. It holds five or six traditional foods (there is disagreement on the number), all of which play a part in the storytelling. Three of the foods symbolize the Jews’ slavery: maror, a bitter herb, often horseradish; charoset, a paste made out of fruits, nuts, and wine representing the mortar Jews used for the Pharaoh’s construction projects; and chazeret, a second bitter herb. Three others are emblems of their freedom: beitzah, a roasted egg; karpas, a vegetable, usually parsley, eaten after being dipped in salt water; and pesach, a lamb shank. After hearing the story and the roles these foods play, we would (finally!) get to feast on a host of delicious delicacies, including homemade gefilte fish, brisket, chicken, macaroons, and whatever else Bubba and her daughters and daughters-in-law prepared.

These trips were a constant until Zede’s death in1962, when I was 12 and my parents adopted a new tradition. We stayed home and had seder with the Sprechers, the first family we met after moving to Virginia. Over the next 60 years, some 40 relatives and friends—whom I’ve long since come to think of as my “family”—have come from around the United States, Israel, and the Netherlands to mark Passover at the Sprechers’ home; it’s a tradition that’s lasted through the deaths of my parents and the elder Sprechers, countless marriages, and the birth of beloved children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Before I became a metalsmith, I didn’t pay much attention to what the seder plates looked like. In my memory they were simply round, silver or ceramic, and big. As I’ve reviewed my memories of seders past, though, I’ve come to appreciate that what ties my family’s ongoing practices together—making them traditions as opposed to one-off dinners—is not only the emphasis on family (biological and beyond), the Exodus story, and the customary foods, but the seder plate itself. I’ve also become convinced that the best way to examine almost any tradition is to understand the rituals and ritualistic objects that give it shape.

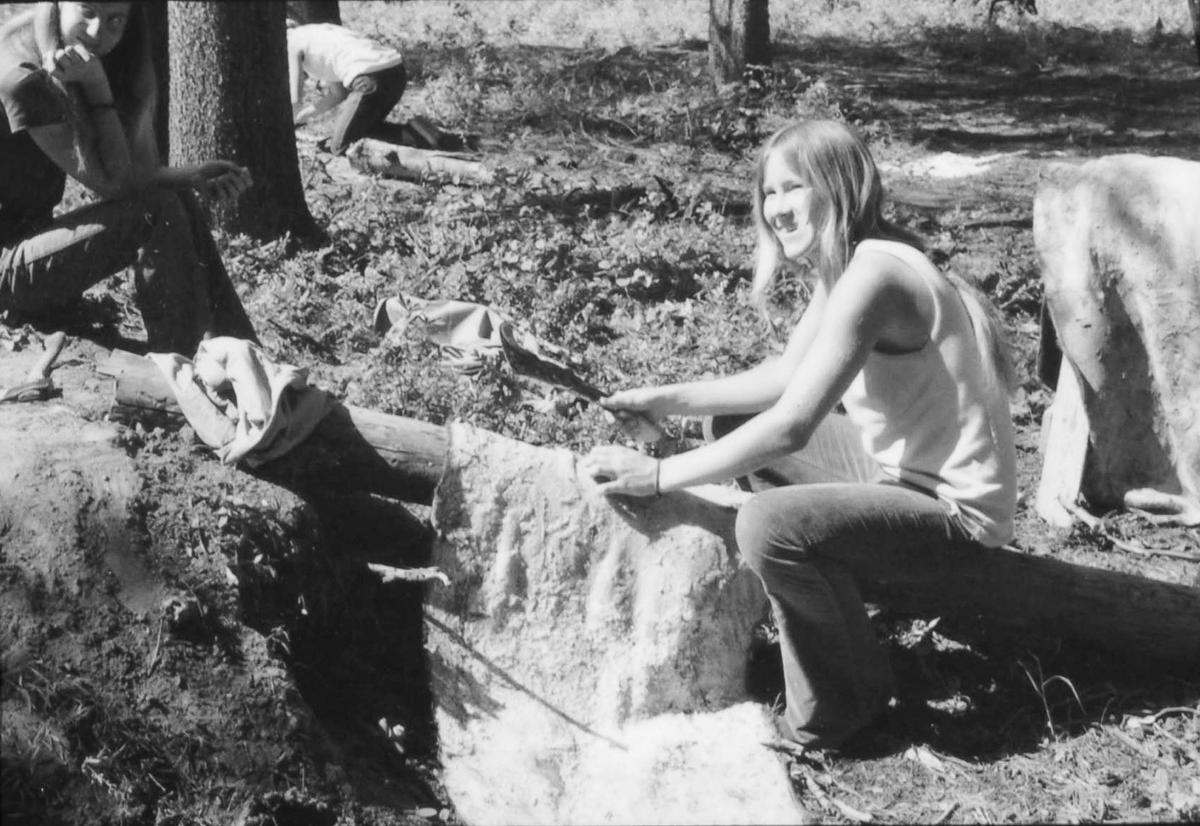

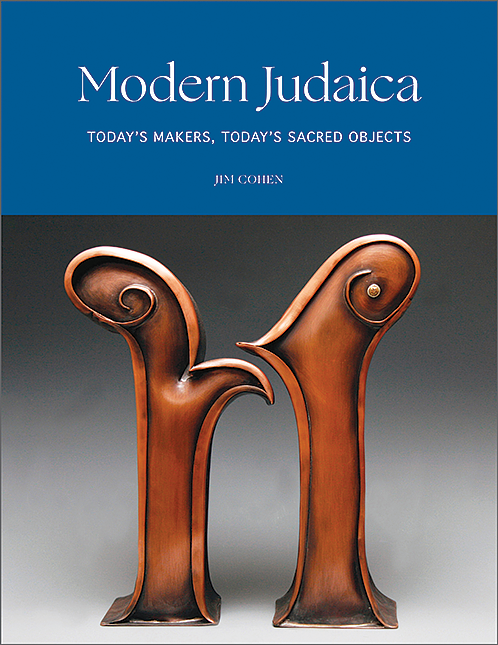

In 2020, publisher Peter Schiffer was at an American Craft Council show in Baltimore and met Jim Cohen, the author of this article. A former Pentagon attorney, Cohen is now a metalsmith. Over the ensuing months, the two collaborated on Cohen's book Modern Judaica: Today’s Makers, Today’s Sacred Objects (Schiffer Publishing, 2022).