Growing up, I always felt like a nameplate was a rite of passage. If you accomplished something and leveled up a step in your life, you might get this badge of honor, this medal. My earliest memories of nameplates were seeing the girlfriends of my older cousins and the older women in my family wearing them, and me feeling like, “when will it be my turn?”

I’m from Van Nuys, California—it’s the 818, it’s in the Valley. I grew up in an apartment complex that was very Black, Latino, and Asian American, and I think that when you grow up with not very much, you take extra good care of the little things and you show out in a different way, whether it’s through your sneakers or even the way you iron your clothes. You take care of your white T-shirts. That’s how you assert who you are. I always felt a nameplate was a way to show off your fly, to let people know like, “I’m here, this is who I am, this is what I do. Maybe you can or can’t pronounce my name, or maybe this is the only name that you get to know, because this might be a nickname, this might be an aka, but this is the me that I choose to present to the world.” My family is Chicano (Apache, Navajo, Mexican, and white) and I also have nieces who are Filipino, Black, and Latina. Our identities can be really complicated, but the commonalities of the nameplate bring us together. These objects are heirlooms: a precious metal with the most personal thing you have—your name.

On my block of 10 apartment buildings, every single one was packed with families with intergenerational living situations. In our house, sometimes my grandpa was living with us, sometimes my tías were there, too. Everything you imagine LA looked like in the 1990s, my block was just like that. I was in middle school at that time and car shows were popping, but I was still too young to go. I wanted to use Aqua Net and lip liner, but I had to sneak to do it when I was already at school. It was all still very aspirational, but I got to watch through the older sisters of the girls in the building. I have a cousin who is seven years older than me, and all his girlfriends had their hair gelled, their lips lined, their acrylic nails, and their nameplates. Everybody had a nameplate. And if it wasn’t a nameplate necklace, it was a belt, even just with your initial. Every little opportunity you could get to assert, “This is who I am, this is where I’m from, this is what I rep,” you would take it. It was also something shared cross-culturally. On Saticoy, the street where I grew up, we were all from very similar socioeconomic backgrounds, and despite our ethnic and cultural diversity, the styles and aesthetics I’ve described were not perceived as specific to one group. I was lucky to grow up in a family that was also very conscious of the roots of hip-hop, so that legacy informed my perspective, too.

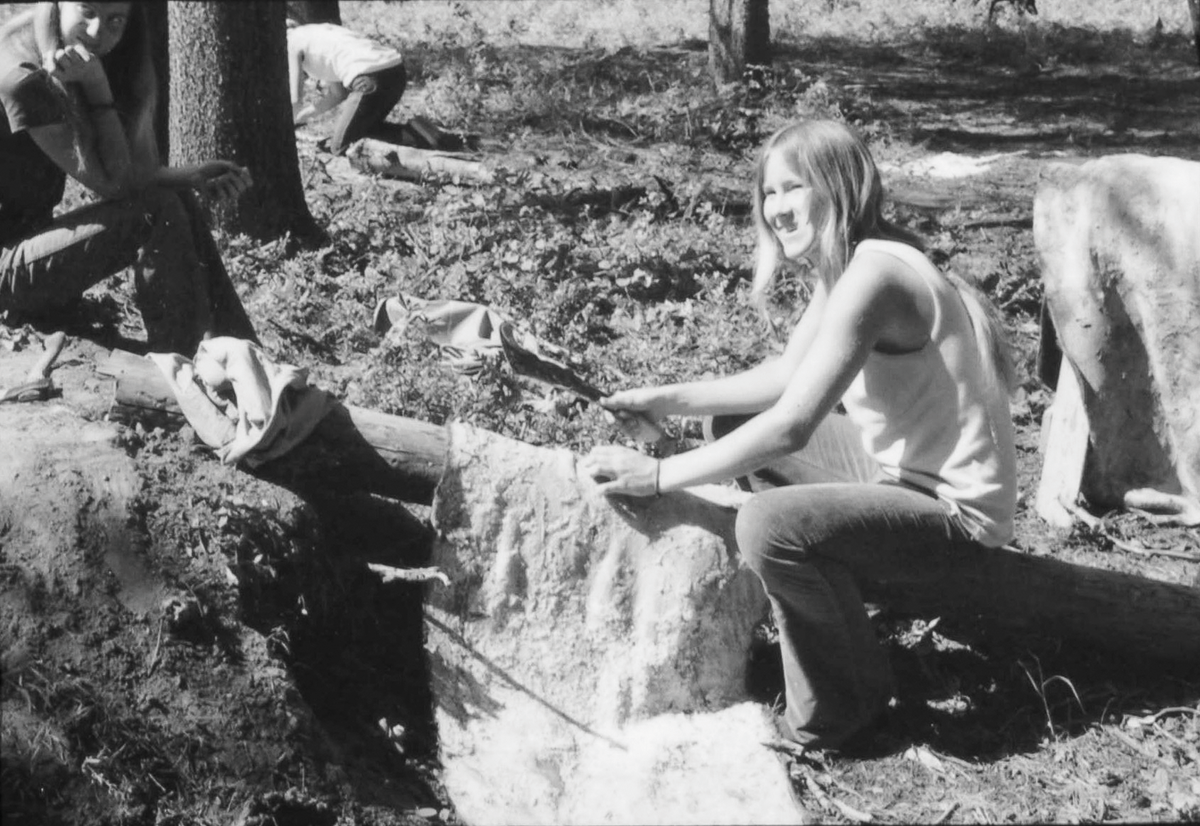

LaLa Romero wears her favorite nameplate necklace and chunky gold hoops on the Joshua Tree, California, set of the music video for her 2017 song “Who’s Playing Who?”