Stories

News, stories, and in-depth features on the artists, makers, organizations, and trends shaping the craft community.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

310 articles

-

ACC’s New Membership Program Connects You to Craft Like Never Before

Join ACC now to support craft artists and connect with benefits in the field.

Digital Only

-

Crafting Your Legacy: A Curator’s Perspective

In the inaugural column of our Craft Coalition series, the Everson Museum of Art’s ceramics curator explains how artists can get their work into museum collections.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristy Moreno

Kristy Moreno’s clay sculptures of future ancestors are avatars of a better tomorrow.

Digital Only

-

Spector Family Foundation Launches New Craft Prize

The three-pronged initiative includes funding for early-career artists.

Digital Only

-

10 ACC Stories to Feed Your Spirit as You Build Community Through Craft

Craft, in all its forms and fullness, isn’t a fair-weather nicety. It is a constellation of practices and values that deepen our humanity and reflect it back to us, and foster the person-to-person bonds on which communities and societies depend.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristin Colombano

Ancient technique and dreamy landscapes collide in Kristin Colombano’s painterly felted textiles.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Leah Woods

Leah Woods’s work with the New Hampshire Furniture Masters has brought her from galleries to prison classrooms.

Digital Only

-

Understanding the Field

A new essay by Jenni Sorkin considers the Center for Craft’s impactful Craft Research Fund.

Digital Only

-

Joyce Lin Wins 2025 John D. Mineck Fellowship

Houston-based Joyce Lin's uncanny furniture forms have earned her a prestigious fellowship from the John D. Mineck Foundation.

Digital Only

-

Treasures from the Collection

A cataloger for the American Craft Council Archives reflects on her long, strange trip through two decades of magazine back issues.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Cait Nolan

For natural dyer and quilter Cait Nolan, creation follows nature’s rhythms. In The Queue, the New Jersey–based artist discusses the cadence of her work, the power of collaboration and asking for help, and learning from an indigo-dyeing master.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

![]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

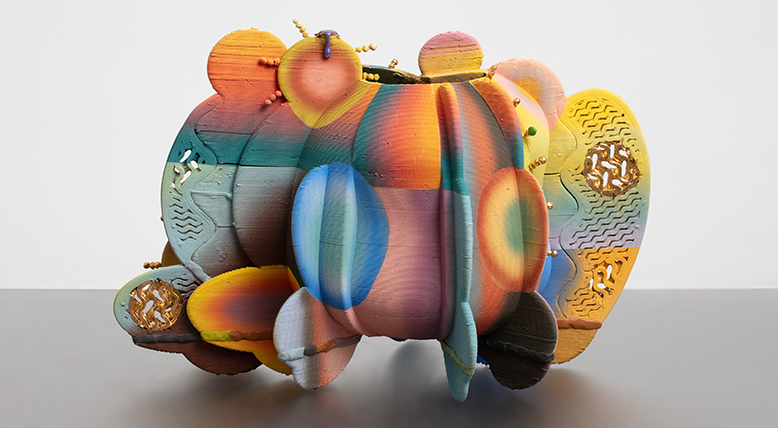

![Multicolored, multi-textured stoneware vessel]() Free To Read

Free To ReadAnother Dimension

Ceramist Jolie Ngo is creating intricate, ebullient work that brings together craft and emerging technology.

Winter 2026

-

![Large hand-dyed quilt held up in a field of grasses]() Free To Read

Free To ReadStitched from the Soil

In a medium often focused on uniformity and speed, quiltmaker Cait Nolan relishes process, repetition, and giving back.

Winter 2026

-

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadOut of the Elements

New York–based designer Shaina Tabak’s fecund imagination pushes materials to the brink.

Winter 2026

-

![Woodworking professor and student]() Free To Read

Free To ReadHead and Hand

The American College of the Building Arts blends liberal arts courses and building-trades training in a four-year degree.

Winter 2026

-

![]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadPermanent Marker

Washington glass artist Dan Friday finds enduring forms for his ancestral Coast Salish history.

Winter 2026

-

![Pinch formed pedestal vase with intricate leaves and green glaze.]() Free To Read

Free To ReadMusings in Clay

Paul S. Briggs’s process-driven, spiritual ceramics practice probes his inner life.

Winter 2026

-

![Musicians, dancers, and onlookers gather at a Milwaukee event center for a fandango, at which son jarocho music is played.]() Free To Read

Free To ReadCarving Out a Musical Tradition

Modern makers look to old-school methods while reviving son jarocho culture.

Winter 2026

-

The Scene: Craft in Santa Fe

Local artists share the people and places that define Santa Fe, a city with a complex history that’s a nexus of rich cultural influences.

Winter 2026

CeramicsClothingFurniture -

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadFelting with Feeling

Based in San Francisco, maker Kristin Colombano’s bespoke, painterly textiles are as dreamy as they are functional.

Winter 2026

-

![Opening exhibition]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadMood Lighting

Each of these four handmade sconces—crafted with unique materials, textures, and shapes—radiates a distinct mood.

Winter 2026

Story categories.

-

Craft News

Timely, topical stories on the artists, makers, and organizations shaping the craft field.

-

Interviews & Profiles

Inspiration and insight from and about makers.

-

Features & Essays

Expert voices dig deep into craft-related subjects.

-

Craft Around the Country

Regional craft reporting and storytelling.

-

Craft Media

Books, periodicals, videos, and podcasts highlighting craft.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.