Stories

News, stories, and in-depth features on the artists, makers, organizations, and trends shaping the craft community.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

318 articles

-

A Clothing Designer’s Careful Dance

Pittsburgh designer and maker Rona Chang balances family life and running a sustainable clothing brand.

Digital Only

ClothingFiber & Textiles -

In Glass Objects, A Radiant Optimism

SaraBeth Post Eskuche channels color and energy into her vivid glass jewelry, home wares, and sculptures.

Digital Only

GlassJewelry -

A River Runs Through It: Water | Craft at the Minnesota Marine Arts Museum

In a new exhibition at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum, seven craft artists explore material history, generational knowledge, and ecological lament through an aquatic lens.

Digital Only

BasketryExhibitionsFiber & TextilesMixed Media -

Worn on the Body

A new exhibition at Kansas City’s Belger Crane Yard Studios celebrates handmade adornment.

Digital Only

ClothingExhibitionsJewelryMixed Media -

A Patchwork of Peace

Buddhist monks walk across the US draped in robes rich in history and community.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

A Delicate Balance

The founder of A Nod to Design pairs beads and chains in her harmonious jewelry designs.

Digital Only

GlassJewelryMetal -

Furniture Problems, Artfully Solved

Eric Carr aims to satisfy unique client needs with his fine studio furniture.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

Valentine’s Day Iron Pour Welcomes Metalsmiths and the Metal-Curious

Collaboration, mentorship, and experimentation are at the heart of Pour’n Yer Heart Out, an annual community event in Wisconsin’s capital city.

Digital Only

EventsMetal -

Crafting Your Legacy: A Curator’s Perspective

In the inaugural column of our Craft Coalition series, the Everson Museum of Art’s ceramics curator explains how artists can get their work into museum collections.

Digital Only

-

ACC’s New Membership Program Connects You to Craft Like Never Before

Join ACC now to support craft artists and connect with benefits in the field.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristy Moreno

Kristy Moreno’s clay sculptures of future ancestors are avatars of a better tomorrow.

Digital Only

Ceramics -

Spector Family Foundation Launches New Craft Prize

The three-pronged initiative includes funding for early-career artists.

Digital Only

-

10 ACC Stories to Feed Your Spirit as You Build Community Through Craft

Craft, in all its forms and fullness, isn’t a fair-weather nicety. It is a constellation of practices and values that deepen our humanity and reflect it back to us, and foster the person-to-person bonds on which communities and societies depend.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristin Colombano

Ancient technique and dreamy landscapes collide in Kristin Colombano’s painterly felted textiles.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Leah Woods

Leah Woods’s work with the New Hampshire Furniture Masters has brought her from galleries to prison classrooms.

Digital Only

-

Understanding the Field

A new essay by Jenni Sorkin considers the Center for Craft’s impactful Craft Research Fund.

Digital Only

-

Joyce Lin Wins 2025 John D. Mineck Fellowship

Houston-based Joyce Lin's uncanny furniture forms have earned her a prestigious fellowship from the John D. Mineck Foundation.

Digital Only

-

Treasures from the Collection

A cataloger for the American Craft Council Archives reflects on her long, strange trip through two decades of magazine back issues.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Cait Nolan

For natural dyer and quilter Cait Nolan, creation follows nature’s rhythms. In The Queue, the New Jersey–based artist discusses the cadence of her work, the power of collaboration and asking for help, and learning from an indigo-dyeing master.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

![]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

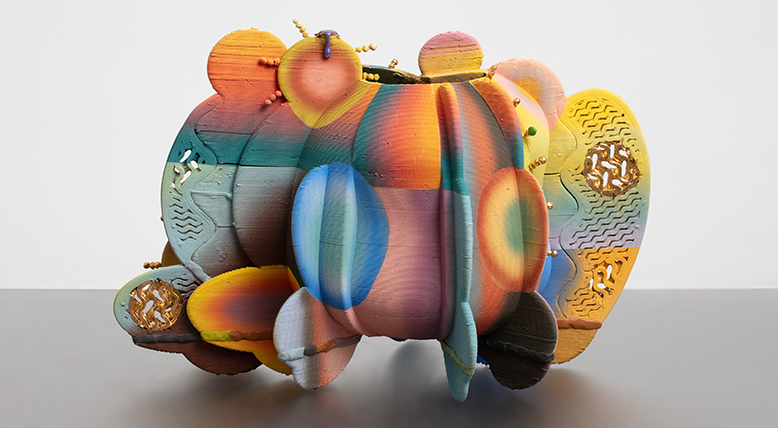

![Multicolored, multi-textured stoneware vessel]() Free To Read

Free To ReadAnother Dimension

Ceramist Jolie Ngo is creating intricate, ebullient work that brings together craft and emerging technology.

Winter 2026

-

![Large hand-dyed quilt held up in a field of grasses]() Free To Read

Free To ReadStitched from the Soil

In a medium often focused on uniformity and speed, quiltmaker Cait Nolan relishes process, repetition, and giving back.

Winter 2026

-

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadOut of the Elements

New York–based designer Shaina Tabak’s fecund imagination pushes materials to the brink.

Winter 2026

-

![Woodworking professor and student]() Free To Read

Free To ReadHead and Hand

The American College of the Building Arts blends liberal arts courses and building-trades training in a four-year degree.

Winter 2026

Story categories.

-

Craft News

Timely, topical stories on the artists, makers, and organizations shaping the craft field.

-

Interviews & Profiles

Inspiration and insight from and about makers.

-

Features & Essays

Expert voices dig deep into craft-related subjects.

-

Craft Around the Country

Regional craft reporting and storytelling.

-

Craft Media

Books, periodicals, videos, and podcasts highlighting craft.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.