Stories

News, stories, and in-depth features on the artists, makers, organizations, and trends shaping the craft community.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

324 articles

-

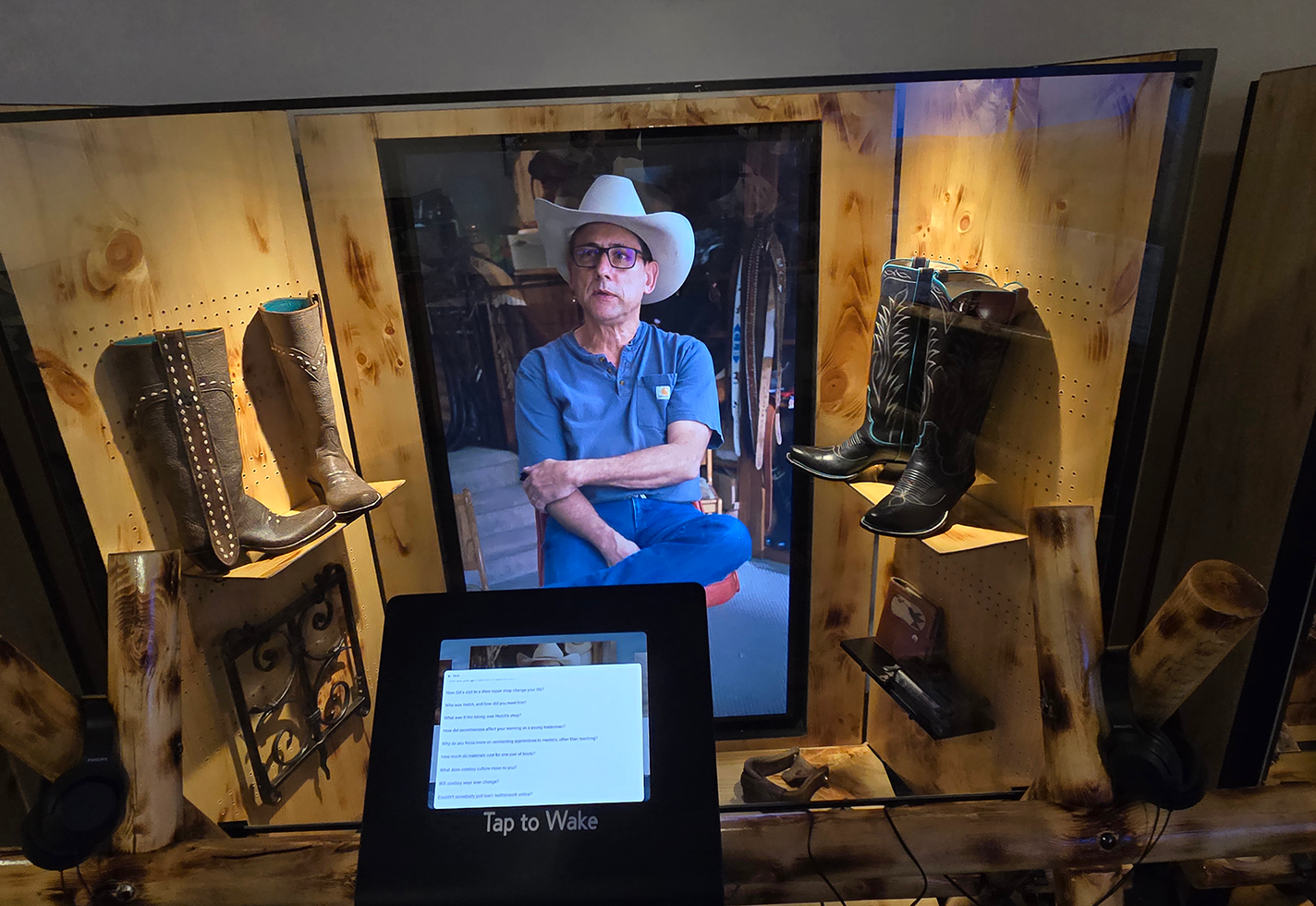

At the Cowboy Arts and Gear Museum, A Contest and Auction Forged in Tradition

The Cowboy Arts and Gear Museum’s annual Bits and Rawhide Reins Contest and Auction celebrates Western craftsmanship.

Digital Only

Fiber & TextilesMetal -

At Home on the Range

A traveling exhibition from the Cowboy Trades Association brings Western tradecraft to audiences across the western US in 2026.

Digital Only

ExhibitionsFiber & TextilesMetal -

A Craft Community in the High Country

The Rocky Mountain Folk School fosters year-round creativity and a pathway to Western trades high up in the mountains.

Digital Only

CeramicsFiber & TextilesGlassMetal -

Silver River Weaves Again

After a devastating flood, the North Carolina chair caning institution returns in a new space.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

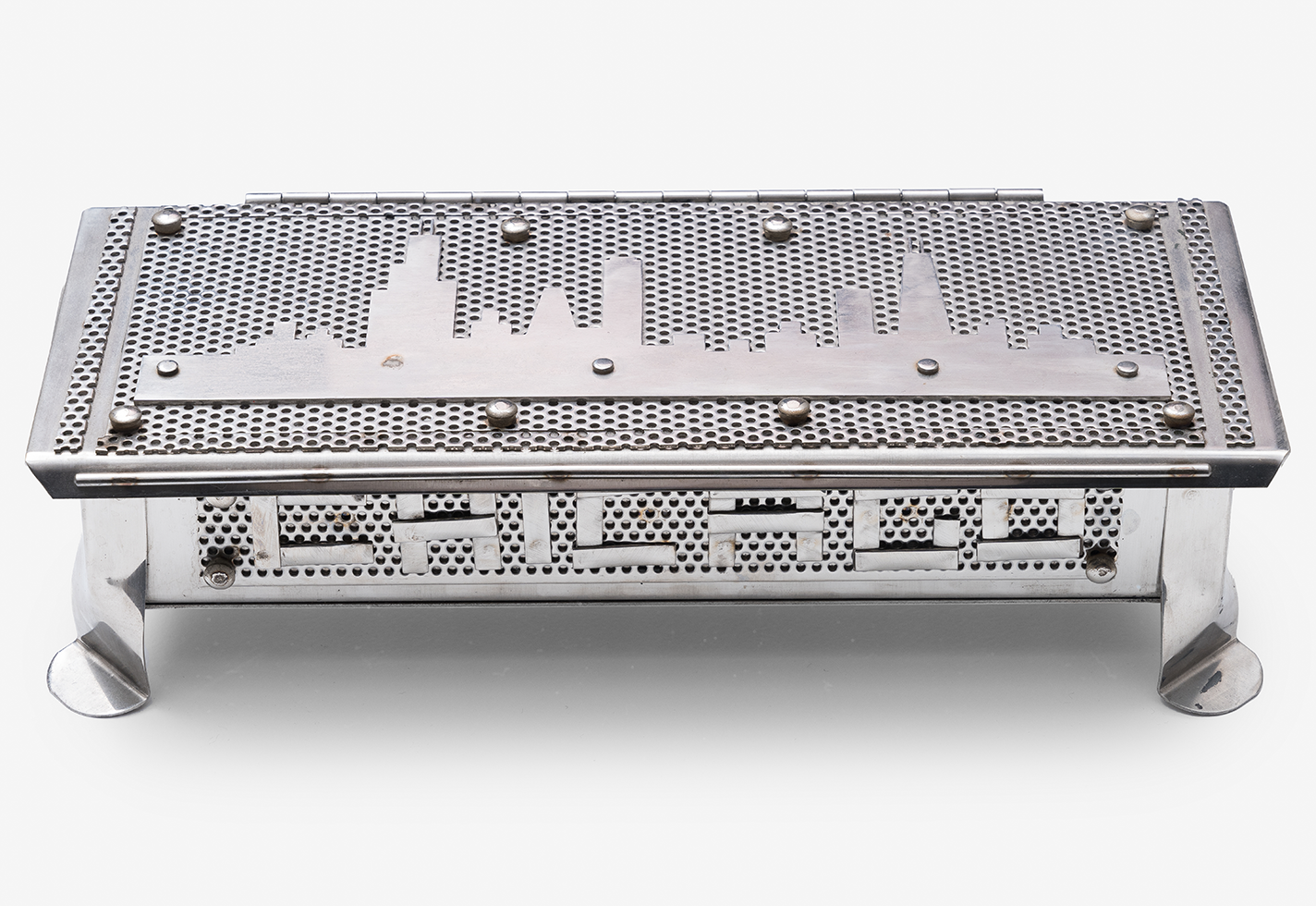

In a Chicago Exhibition, A Focus on Migration and Self-Taught Artists

Craft mediums feature prominently in Catalyst, an exhibition spotlighting self-taught immigrant artists at the Intuit Art Museum.

Digital Only

Exhibitions -

Crafted in the Mountains Traces the History of Appalachian Craft

A new exhibition at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts considers the shifting landscape of craft in the region.

Digital Only

Exhibitions -

A Clothing Designer’s Careful Dance

Pittsburgh designer and maker Rona Chang balances family life and running a sustainable clothing brand.

Digital Only

ClothingFiber & Textiles -

In Glass Objects, A Radiant Optimism

SaraBeth Post Eskuche channels color and energy into her vivid glass jewelry, home wares, and sculptures.

Digital Only

GlassJewelry -

A River Runs Through It: Water | Craft at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum

In a new exhibition at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum, seven craft artists explore material history, generational knowledge, and ecological lament through an aquatic lens.

Digital Only

BasketryExhibitionsFiber & TextilesMixed Media -

Worn on the Body

A new exhibition at Kansas City’s Belger Crane Yard Studios celebrates handmade adornment.

Digital Only

ClothingExhibitionsJewelryMixed Media -

A Patchwork of Peace

Buddhist monks walk across the US draped in robes rich in history and community.

Digital Only

Fiber & Textiles -

A Delicate Balance

The founder of A Nod to Design pairs beads and chains in her harmonious jewelry designs.

Digital Only

GlassJewelryMetal -

Furniture Problems, Artfully Solved

Eric Carr aims to satisfy unique client needs with his fine studio furniture.

Digital Only

FurnitureWood -

Valentine’s Day Iron Pour Welcomes Metalsmiths and the Metal-Curious

Collaboration, mentorship, and experimentation are at the heart of Pour’n Yer Heart Out, an annual community event in Wisconsin’s capital city.

Digital Only

EventsMetal -

Crafting Your Legacy: A Curator’s Perspective

In the inaugural column of our Craft Coalition series, the Everson Museum of Art’s ceramics curator explains how artists can get their work into museum collections.

Digital Only

-

ACC’s New Membership Program Connects You to Craft Like Never Before

Join ACC now to support craft artists and connect with benefits in the field.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristy Moreno

Kristy Moreno’s clay sculptures of future ancestors are avatars of a better tomorrow.

Digital Only

Ceramics -

Spector Family Foundation Launches New Craft Prize

The three-pronged initiative includes funding for early-career artists.

Digital Only

-

10 ACC Stories to Feed Your Spirit as You Build Community Through Craft

Craft, in all its forms and fullness, isn’t a fair-weather nicety. It is a constellation of practices and values that deepen our humanity and reflect it back to us, and foster the person-to-person bonds on which communities and societies depend.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Kristin Colombano

Ancient technique and dreamy landscapes collide in Kristin Colombano’s painterly felted textiles.

Digital Only

-

The Queue: Leah Woods

Leah Woods’s work with the New Hampshire Furniture Masters has brought her from galleries to prison classrooms.

Digital Only

-

Understanding the Field

A new essay by Jenni Sorkin considers the Center for Craft’s impactful Craft Research Fund.

Digital Only

-

Joyce Lin Wins 2025 John D. Mineck Fellowship

Houston-based Joyce Lin's uncanny furniture forms have earned her a prestigious fellowship from the John D. Mineck Foundation.

Digital Only

-

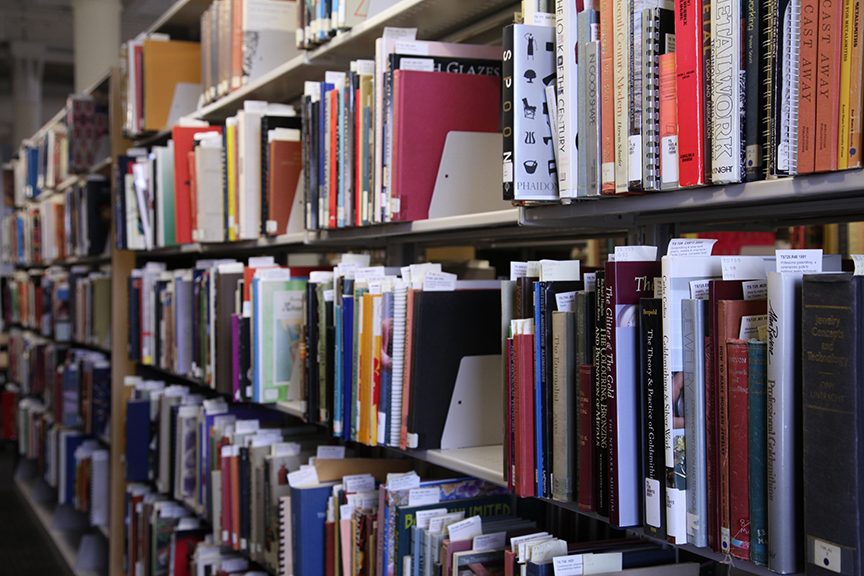

Treasures from the Collection

A cataloger for the American Craft Council Archives reflects on her long, strange trip through two decades of magazine back issues.

Digital Only

Story categories.

-

Craft News

Timely, topical stories on the artists, makers, and organizations shaping the craft field.

-

Interviews & Profiles

Inspiration and insight from and about makers.

-

Features & Essays

Expert voices dig deep into craft-related subjects.

-

Craft Around the Country

Regional craft reporting and storytelling.

-

Craft Media

Books, periodicals, videos, and podcasts highlighting craft.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.