Crafted stories.

Every object has a maker, and every maker has a story. Discover the narratives of emerging and established artists, the evolution of their creations, and how the everyday is made more extraordinary through the fine art of craft.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

180 articles

-

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Raul De Lara

New York City–based woodworker Raul De Lara coaxes wood into expressive sculptures, often depicting outsized plants and unusable tools.

Digital Only

The Queue -

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

ACC NewsFree To ReadInterview With Geetika Agrawal

ACC sits down with Vacation with an Artist founder, Geetika Agrawal, for a Q&A.

Digital Only

-

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

ACC NewsFree To ReadRemembering Ginny Ruffner

Ginny Ruffner (1952-2025) created sculptures in a variety of media but was known primarily for her use of lampworked glass.

Digital Only

-

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

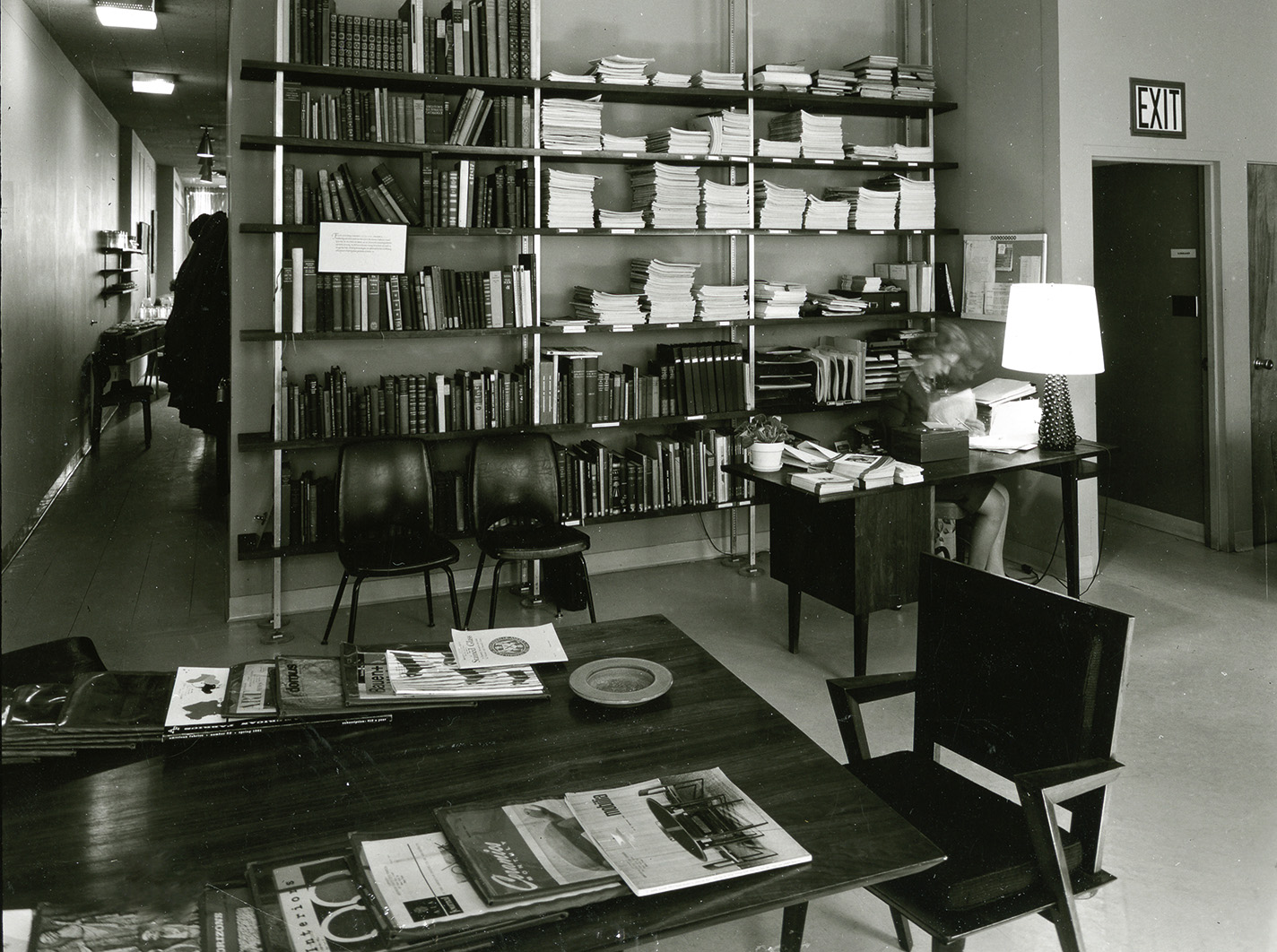

ACC NewsFree To ReadChanges Underway at the ACC Library and Archives

Ensuring that our library and archives materials become more accessible to craft researchers, writers, and advocates for years to come.

Digital Only

-

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Paula Wilson

For Paula Wilson, artmaking is world-building. In The Queue, the Carrizozo, New Mexico–based multidisciplinary artist shares about how she creates the world she wants to live in, the physicality and tools that drive her printmaking practice, and the community around her rural artist-in-residence program.

Digital Only

The Queue -

![Silver bracelet with mosaic inlay]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

ACC NewsFree To ReadA Constant Companion

In the high desert, American Craft magazine keeps two weavers connected to the wider world of craft.

Digital Only

-

![Large terracotta planter and saucer set]() Handcrafted LivingFree To Read

Handcrafted LivingFree To ReadEnchanted Planters

The ceramic vessels here, created by four makers from the Los Angeles area, would bring a California vibe to most any setting.

Spring 2025

Goods -

![Artist Madison Holler wrapped in wool throw.]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadConnective Roots

Drawing on folklore and patterns from her cultural heritage, Madison Holler creates intricate beaded jewelry and sumptuous collaborative designs.

Spring 2025

Features + Profiles

Story categories.

-

Craft Happenings

Browse a timely, curated, and frequently updated list of must-see exhibitions, shows, and other events.

-

Points of View

Essays, craft histories, ideas, analysis, and other perspectives on the significance of craft.

-

Makers

Profiles, interviews, studio tours, and videos on people who are making the world more beautiful.

-

Materials & Processes

Learn about materials and how craftspeople transform them into functional and sculptural works.

-

Handcrafted Living

Discover practical and pleasing handmade goods and stories about living with meaningful objects.

-

Travel

Explore the world of craft by visiting the places and communities where it is created and celebrated.

-

Media Hub

Discover new books, niche periodicals, videos, and podcasts—plus highlights from ACC’s archives.

-

ACC News

Explore the impact of the American Craft Council and the ACC community through stories and updates on our programs, events, artists, and more.

Explore American Craft magazine.

Award-winning journalism in the craft field.

Learn more about one of the country’s leading publications on the diversity of American craft and its makers.

Become a member

Join today and start your craft journey!

Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and get American Craft delivered to your home with a membership to the American Craft Council.