It all started with a seemingly endless stream of eighth graders who swarmed his studio every Wednesday for the glass-blowing demonstrations he’d agreed to do. “They weren’t the least bit interested in me or goblets,” Simpson says. But who wasn’t astounded by the recent Apollo 8 mission photos of Earth rising behind the moon, like a little blue marble with white swirls? So, he says, “One day l decided to make a planet for them, just a simple clear glass sphere with a little blue world inside, to show the kids some of the mechanics of how glass is made, but also to give them something more to think about.”

His first little planets were a big hit. Moreover, Simpson had landed on a potent creative direction, one that would meld interests discovered in childhood with his adult propensity for experimentation with chemistry, materials, and technique. “Over time, the planets became larger and more complex,” says Simpson, a master of understatement.

Now, more than 50 years after the artist took his first gather of glass from a furnace he had built in 1971 with a fellow student at Goddard College, he recalls the events of an ordinary childhood that somehow led to his extraordinary present: Sitting on the back porch of his home in South Salem, New York, with his father, gazing at the moon and stars, pointing out constellations. Family trips to the Hayden Planetarium in the American Museum of Natural History, where he marveled at meteorites and a lunar panorama. Watching the fish tank in his bedroom, a self-contained water world between earth and sky. Mountains of sci-fi novels he “consumed” as a kid, he says. Talk of building a telescope, and attempting to grind a lens for one as an early experiment in glasswork.

Simpson’s first major success began one day while he was experimenting with melting silver on the surface of amethyst glass and—almost by chance—created a unique new kind of glass, a cerulean blue he called “New Mexico.” A client who’d purchased a set of New Mexico goblets told Simpson that “drinking out of them was like drinking from the sky.” Simpson marveled at “how something as utilitarian as a wine goblet could conceptually represent so much more.”

With the income from selling these hand-blown goblets, in 1976 Simpson purchased the farm outside Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, that would become his permanent studio. There, walking from his house to the barn almost every night to check on his glass furnaces, he is often inspired by thunderstorms, the night sky, falling meteors, or a rare aurora borealis.

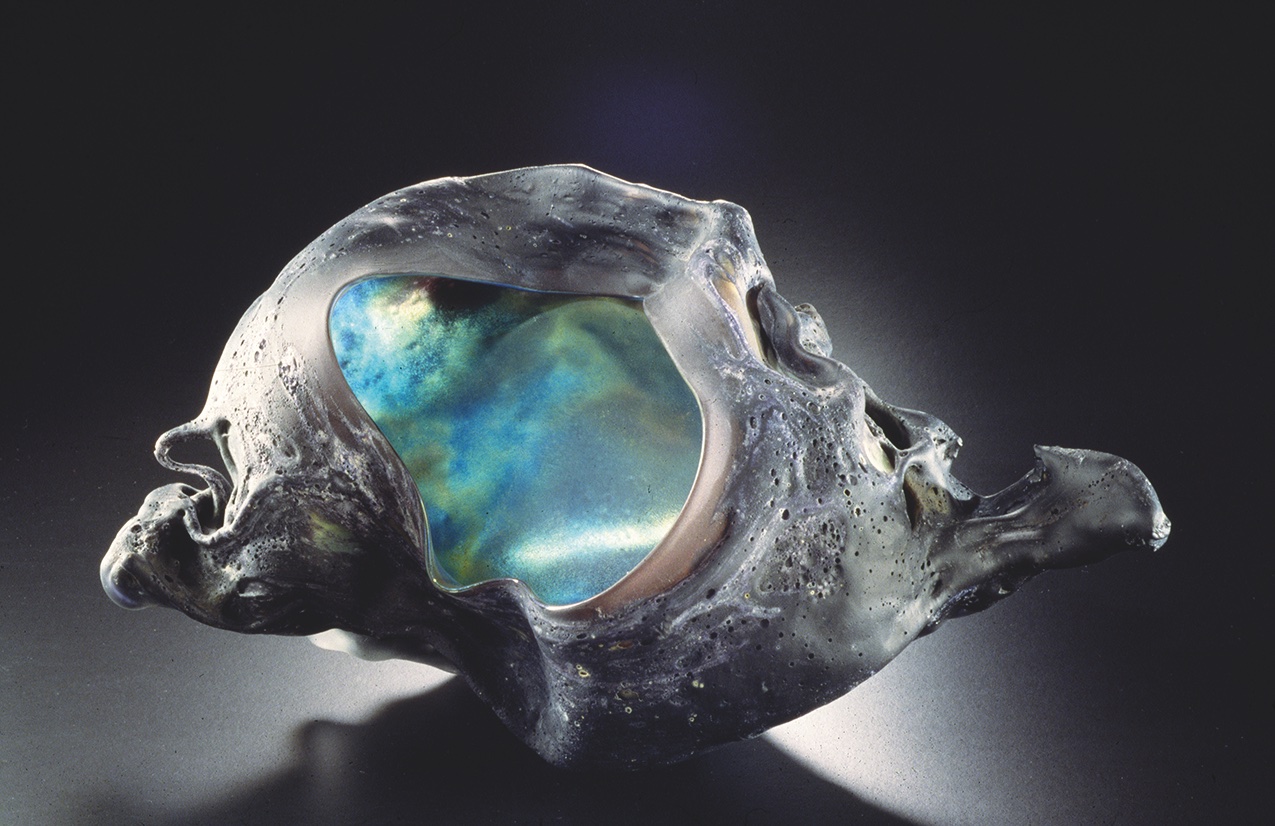

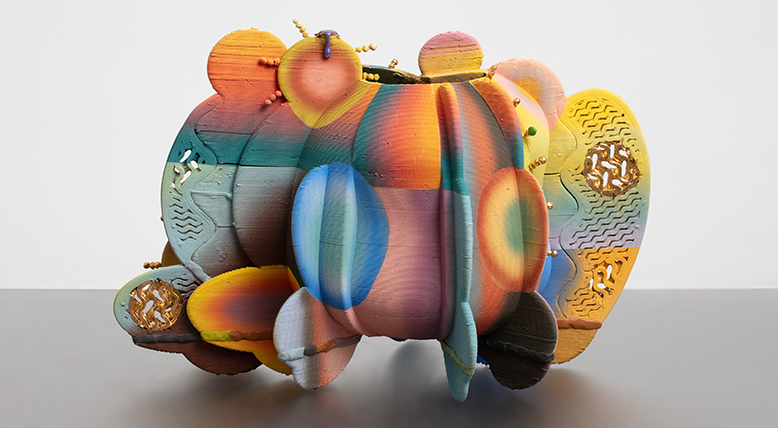

Today, Simpson is revered as a pioneer in the studio-glass movement, having spent the past five decades inventing new color formulas and creating singular glass objects. Pieces in the Planets series are as small as marbles or as large as the 107-pound work from the Megaplanets series that resides at the Corning Museum of Glass. His platters, bowls, vases, “tektites,” “portals,” and other sculptural objects integrate his fascination with the astrophysical with ever more complex explorations into intricately layered colors, forms, and patterns.

One collector, smitten by Simpson’s paperweight-sized planets in a gallery 30 years ago, describes them as impressionistic. “They’re endlessly fascinating, a combination of serendipity and randomness and precision all in exquisite balance, and every time you look at them there’s something more to see.”

Simpson’s cerulean blue New Mexico goblets, 1977, 8.75 in. tall.