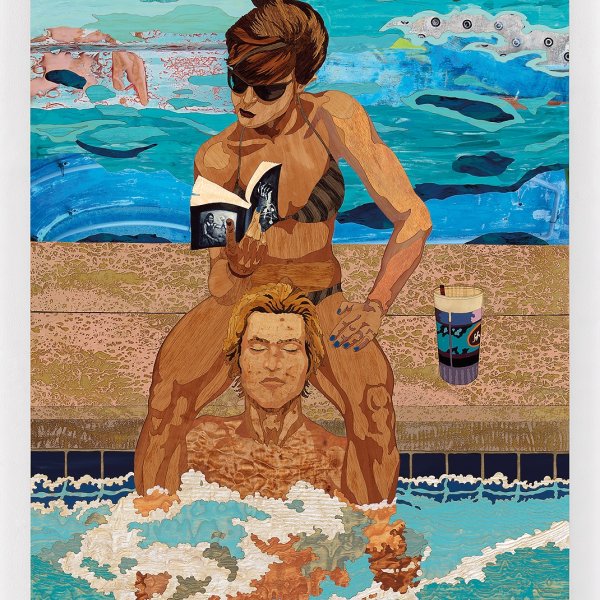

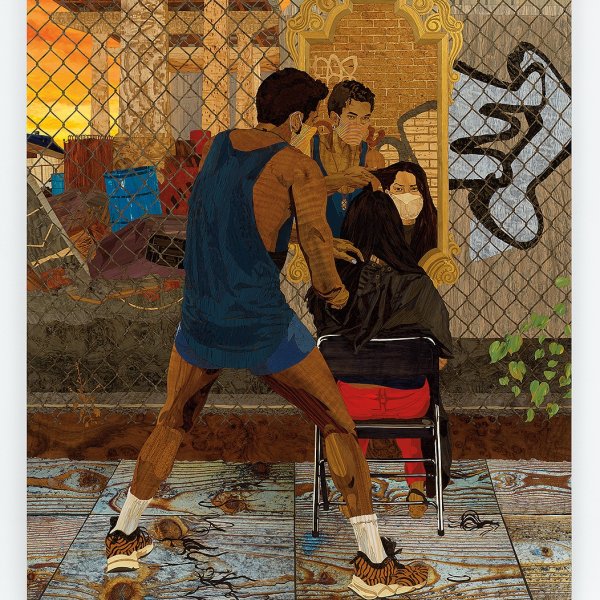

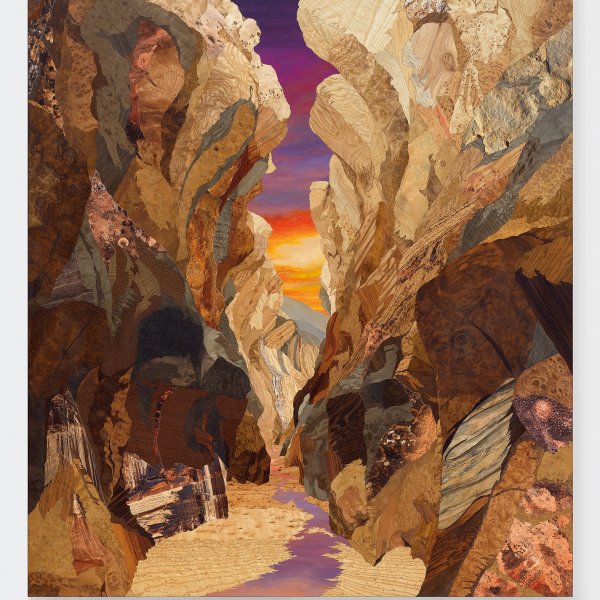

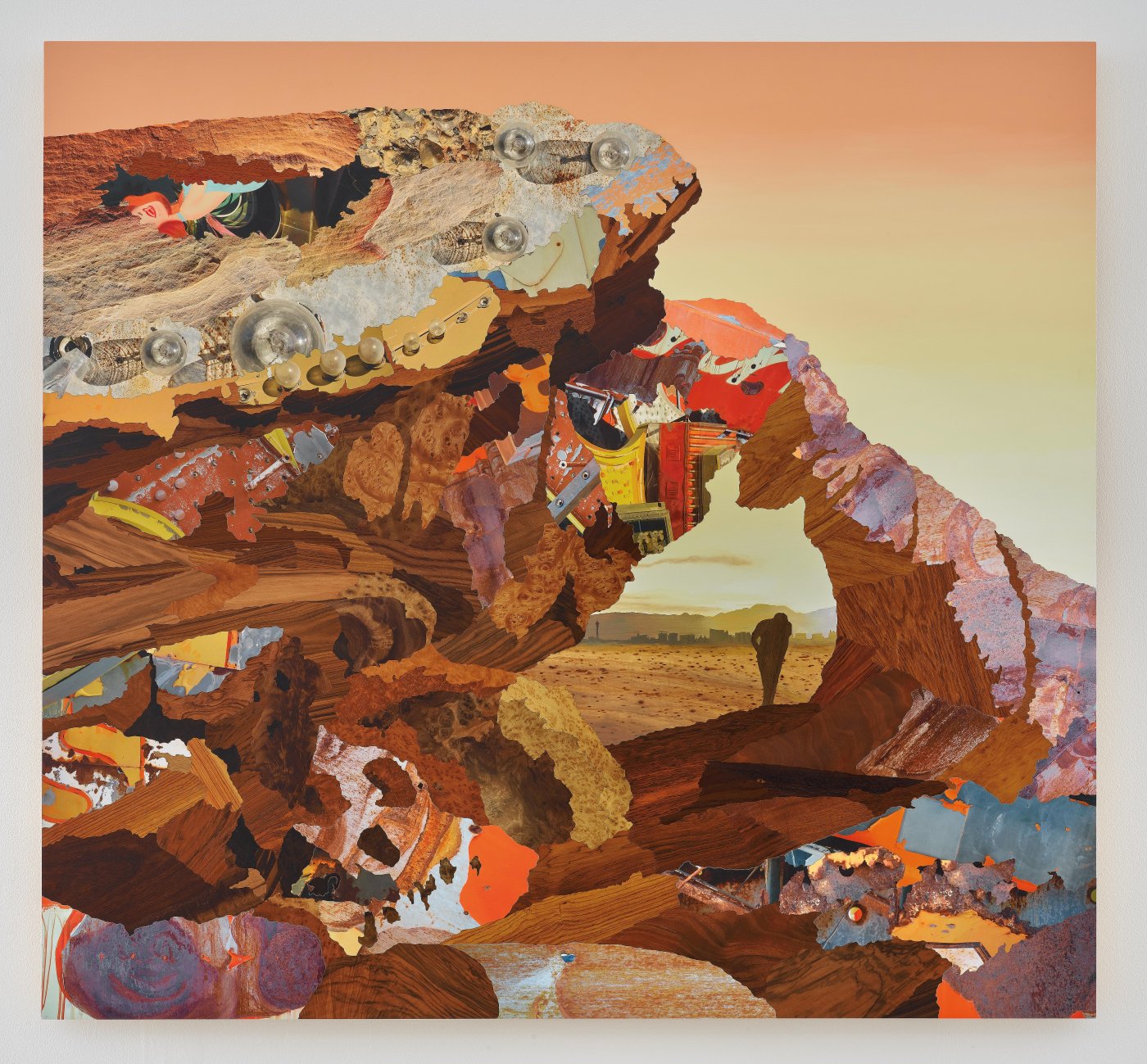

Marquetry hybrid is a synthesis of painting, collage, photography, and wood veneer marquetry on panel. It is a slow and painstaking process. Hours of tedium are gobbled up; days drip away into weeks, months. Often work must be thrown out and attempted again when something doesn’t go right due to technical or aesthetic challenges. It is not a great medium for making art fair deadlines or posting on Instagram. It is glacial and demanding, it can’t be rushed, and it needs to be seen in person to be fully understood. The final form is heavy but very delicate. Transport is a nail-biter.

Physically, it is a workout, running back and forth in the studio, digging through piles of veneer, trying to find the perfect grain/figure/color for a shape. I stretch over tables for hours, taping pieces together prior to gluing, and trying to envision what woods will look like after they change when sanded and shellacked. When it is all done, the marquetry skins must be put on a substrate. Building and gluing panels for them is precise, heavy work with high stakes.

But when I walk through the studio door, a wave of relief washes over me. My studio is on the second floor of a warehouse in Brooklyn and has great light. But it’s not just that. It’s the comfort of knowing I’m here, in my space, and I can work. I still can’t believe I get to be here. I worked jobs I didn’t like for decades before beginning to make art full time. It’s been a while now, but compared to memories of busing tables off the Vegas strip, pathing out guitars in Photoshop for print catalogs, or welding fences in the hot Arizona sun, chasing around tiny chips of wood with an X-Acto seems like bliss. It is on my own terms in a studio space I can control.

Speaking of control, dealing with temperature and humidity in an old leaky warehouse can be an exercise in planning and patience with the weather. Hours spent flattening and cutting wood can be wiped out by a sudden downpour; hydrophilic pieces of veneer start to curl right up and not fit next to each other any longer because different cuts and species of wood absorb moisture at varying rates. I’ve gotten better at anticipating the effects of outside conditions and being flexible in working around these types of days. Don’t cut on wet days (check the weather forecast)!

Marquetry hybrid artist Alison Elizabeth Taylor's Only Castles Burning..., 2017.