For many of Washington’s Indigenous Coast Salish peoples, fish—and salmon in particular—are sacred. Chinook, sockeye, chum, coho, and pink: the five species of salmon native to the Northwest’s waterways are more than just a resource. Since time immemorial, the salmon has been a core symbol of identity and culture for Native peoples like the Lummi, who call themselves the Lhaq’temish, or People of the Sea, reflecting their close ties to the Salish Sea for their livelihood. It is fitting, then, that a salmon was the impetus for Lummi glass artist Dan Friday (Kwul Kwul Tw) to pursue his calling and true identity as a solo artist.

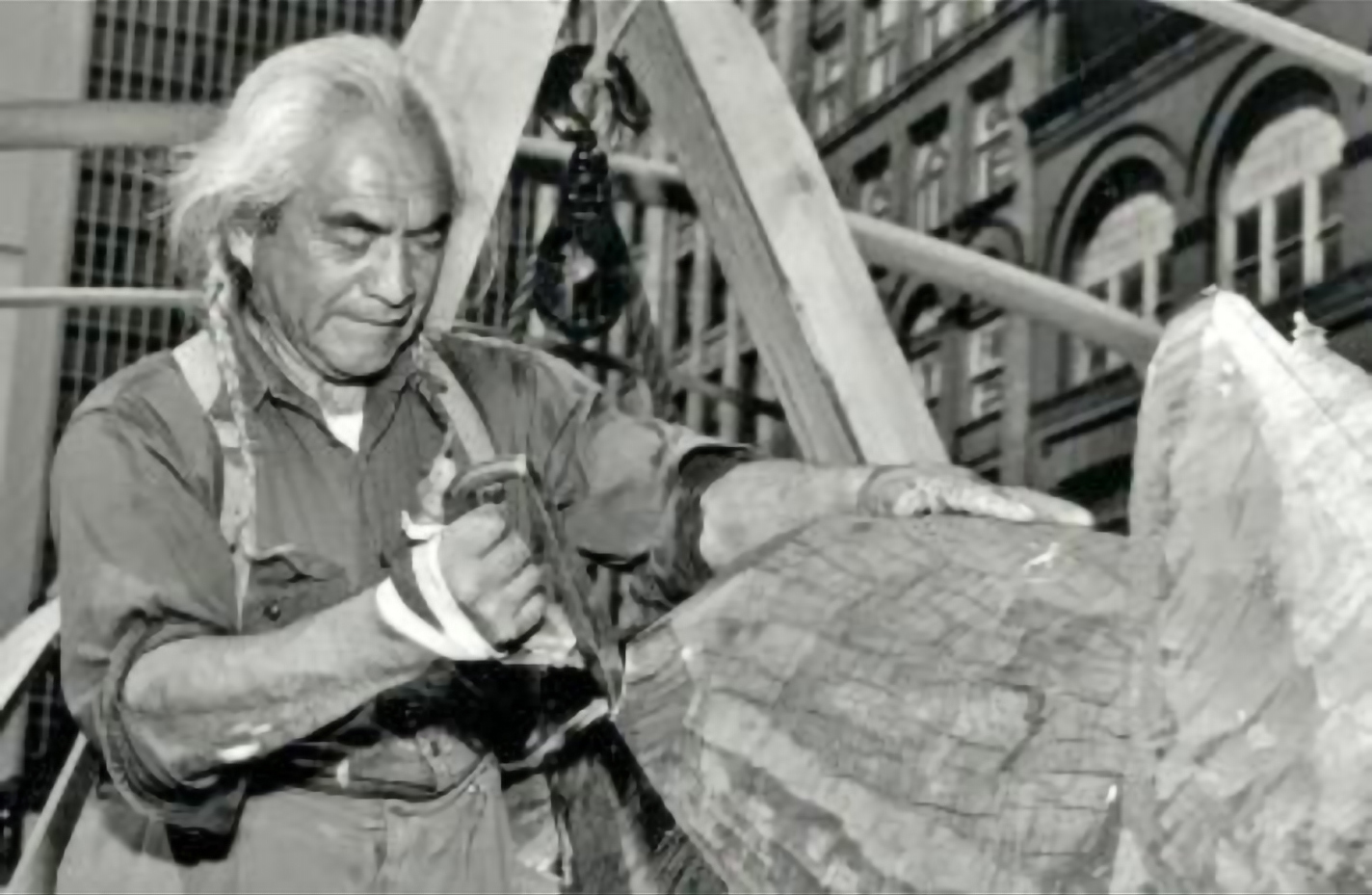

“As soon as I hung the last fish at the Seattle Aquarium, I knew it was time,” says Friday, referring to Schaenexw (Salmon) Run, an installation of 33 glass salmon at the Aquarium’s new Ocean Pavilion on the Seattle waterfront, and his synchronous decision to quit his day job. For decades, Friday worked for legendary Seattle glass artists such as Dale Chihuly, Preston Singletary, and Paul Marioni. Although he cultivated his own studio practice alongside his work for other artists, that project is what pushed Friday to at last make it his full-time job.

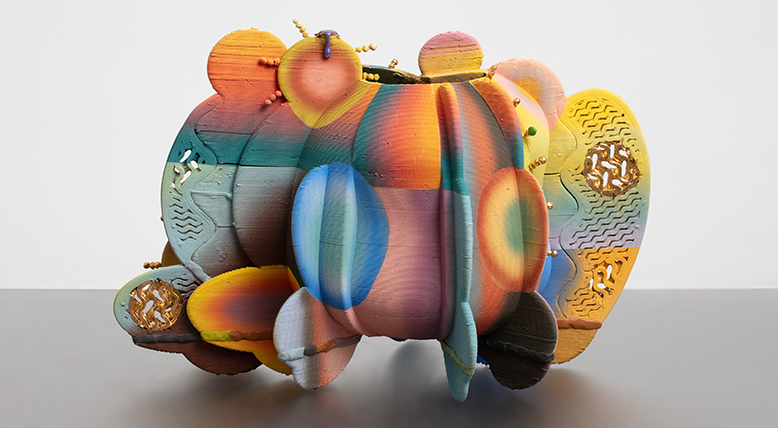

Friday's Kulshan Bear shows the silhouette of Mount Baker. Descendants of his great-great-grandfather Frank Hillaire are known as the bear family.