Throughout the arts in America we are in the presence of a quest for a deeper feeling of presence.

The American potter, isolated from the mass market which makes no demands on his product as a material necessity, is motivated by a personal esthetic and a personal philosophy. Lacking an American pottery tradition, he has looked to the world heritage and made it his own. For this, he has had to study and travel. Today, with his knowledge about himself, his craft and his art—historically, contemporaneously, and geographically— cumulatively greater than ever before, the U.S. craftsman, a lonely, ambitious eclectic, is the most eager in search of his own identity.

All this, then, has made him most susceptible and responsive to the startling achievements of contemporary American painting and sculpture. For better or worse, he has allied himself with a plastic expression that comes from his own culture and his own time, and from an attitude towards work and its processes with which he can identify. The American potter gets inspiration from the top— from the most developed artistic, intuitive consciousness in his society. As always, the artist is led—not by the patron, not by populace, certainly not by the critic—artist is led by artist. The artist is his own culture.

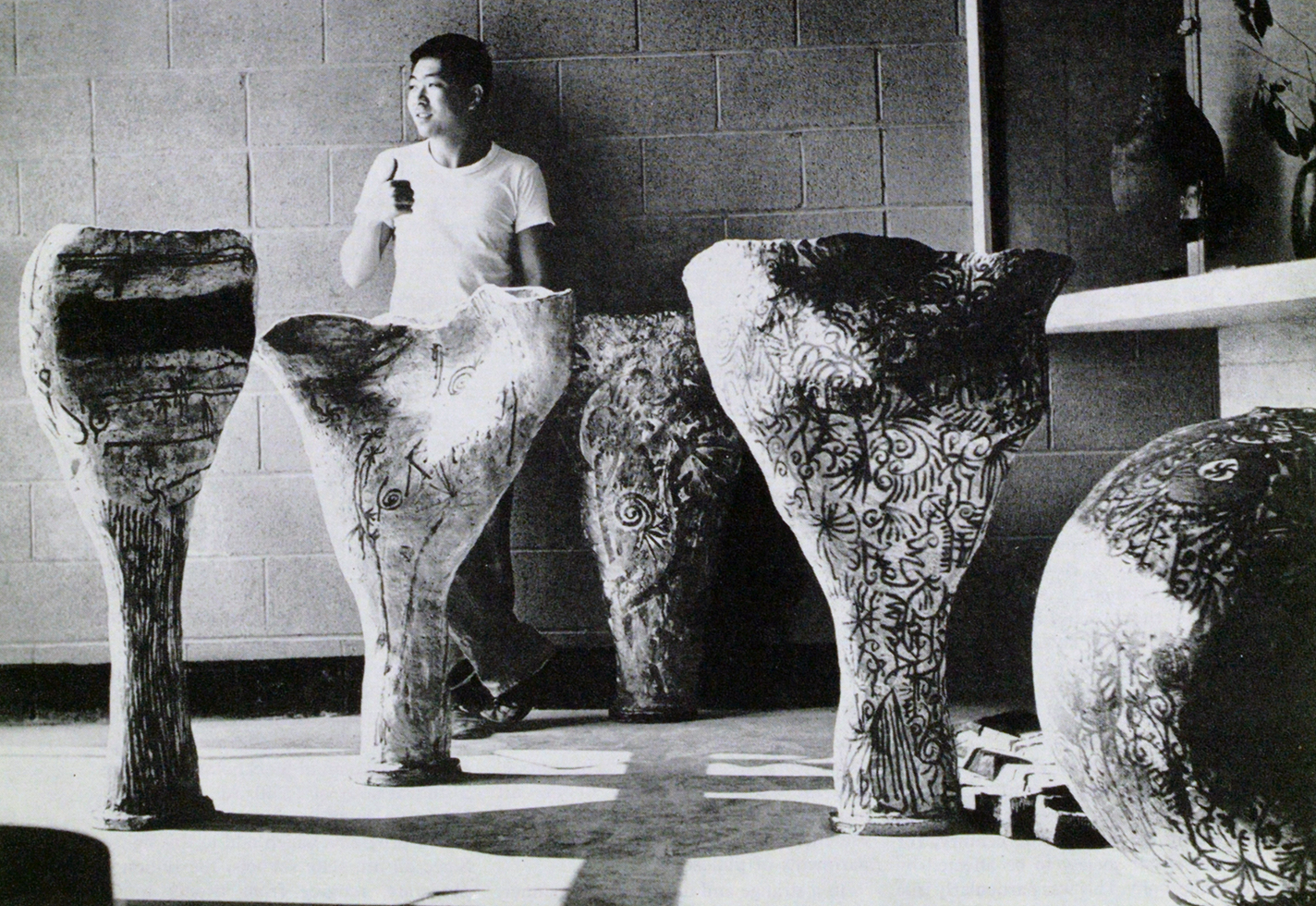

Briefly, the characteristic directions of the new American pottery are: the search for a new ceramic presence, the concern with the energy and excitement of surface, and the attack on the classical, formal rendering.

Pottery, with a continuity that reaches back to the very beginnings of man, has always had a tradition for variety. If there is any one traditional characteristic of American pottery, it is this enormous variety. And if there is anything that distinguishes American plastic expression, it is the forthrightness, the fearlessness, the individuality, the aloneness of each man’s search.

Rose Slivka, American poet and writer, was editor in chief of Craft Horizons from 1959–1979.

* John Kouwenhoven’s documented study of American esthetics, “Made in America,” published by Charles T. Branford Co., 1948.

**The writer does not wish this article to be interpreted as a statement of special partisanship for those potters working with the new forms and motivations. It is an attempt to treat a direction of work which, with its provocative attitudes, has evoked strong response— for is as well as against it. Our partisanship is for creative work in all its variety. We recognize that pottery has as many faces as the people who make it.