In Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, a triptych painted between 1490 and 1510, we see bizarre animals mingling with disrobed men and women, some placidly splashing in the water, others engaged in amorous activities, and yet others taking bites of giant red fruits. It’s an enigmatic masterpiece that has been interpreted as either the ultimate romp or a cautionary tale against sin. One wouldn’t expect to see its images, conceived by a Dutchman in the late Middle Ages, turned into a piñata—those papier-mâché candy containers often seen at kids’ birthday parties—but that’s exactly what Los Angeles–based artist Roberto Benavidez has been doing for more than a decade.

One of his recent sculptures, 2023’s Stigmata Piñata, focuses on a small vignette of the famous painting: a young boy lying on the grass with one leg up, a bird perched on his raised foot, and a plump berry in one hand. Benavidez’s three-dimensional creation looks almost exactly like Bosch’s composition, except he substitutes the fruit with a Mexican-style seven-pointed star, intentionally creating a cultural mashup.

“I think of the hybrid creatures in this painting as a subtle reference to myself being mixed-race,” he says. “As a sculptor, I get so much joy in re-creating them in 3D form. I really like the balance between cute and scary in them. That being said, there is also this religious parallel between the piñata and the theme of the painting that connects the two.”

Benavidez grew up in a small town in South Texas, in an area where “art wasn’t a thing.” He was raised Catholic by his mother, who is white, and his father, who was born in Texas but identifies as Mexican. As a young boy, he remembers going to Mass and being much more interested in the visuals of the church than in religion itself. “That may be where I developed my medieval aesthetic,” he says, tongue in cheek.

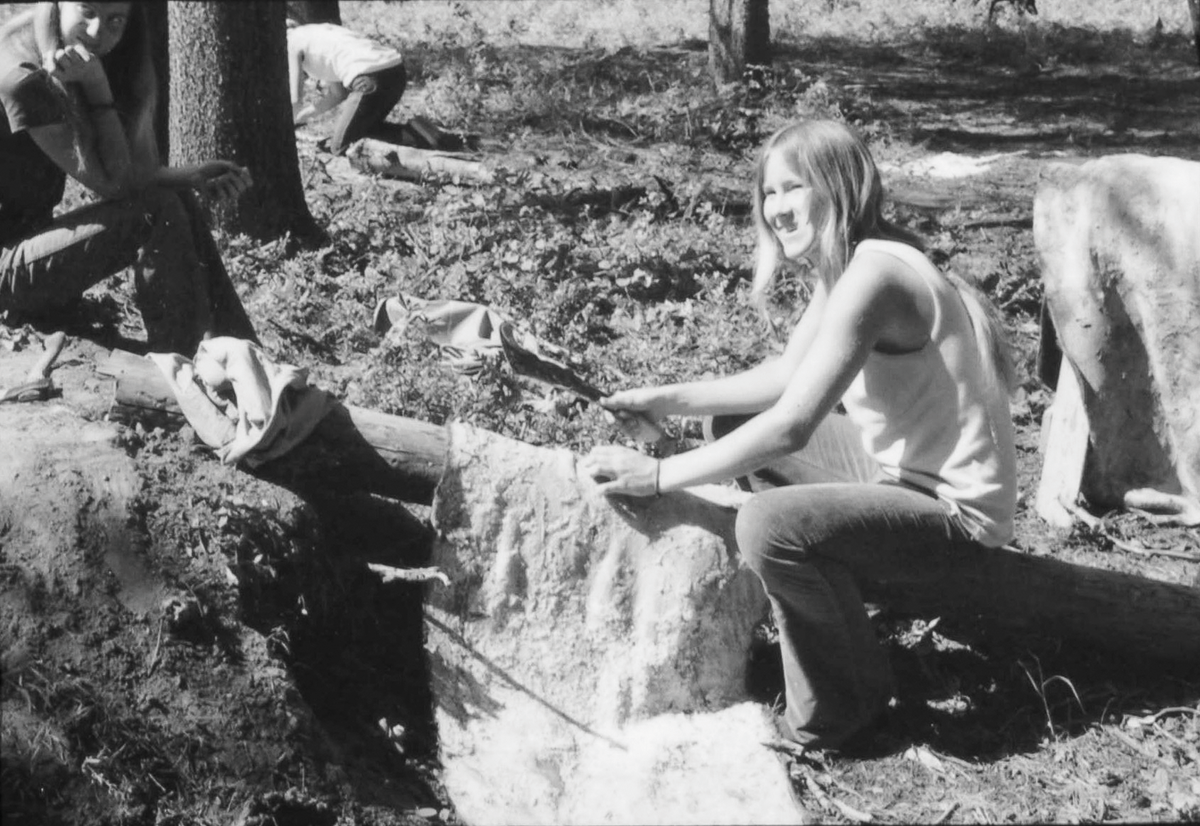

Roberto Benavidez works on a commissioned piece from his Illuminated Piñata series, examining the flow of patterns.