2 by 2

2 by 2

Tim Tate and Marc Petrovic agree: Their two recent collaborations, Apothecarium Moderne and Seven Deadly Sins, were better because they made them together.

Ask Tim Tate about the origin of his recent collaborations with Marc Petrovic - if you can beat him to the punch. The friendly, boisterous artist has a habit of plunging into stories, leaping ahead and around, as if his brain were a rocket fueled by honesty.

"I posted a cat - playing a piano - on Facebook," he volunteers. "I'm not proud - I thought it was cute, and I don't care who knows." In response to said viral video, the chief curator at New York's Museum of Arts and Design posted a comment, joking that he ought to have that cat perform at his museum. Tate pounced, pitched an idea, and, as he tells it, had a slot within 24 hours in MAD's "Dead or Alive" exhibition, a prestigious 2010 showcase of artists incorporating organic materials in sculpture and installation. Tate contacted Petrovic - another artist working in glass, a friend, and a mentor of sorts - and he agreed to collaborate. Apothecarium Moderne, a set of nine cures for modern ills in domed glass reliquaries, was born. Seven Deadly Sins was lurking just around the corner.

If this sounds like a wholly 21st-century story, that's because it is - but not only because it has roots in social media. This is the age of Wikipedia, after all, of open-source software and Creative Commons licenses. Connectivity and collaboration aren't only buzzwords; they're molding our lives. And in their two recent, exquisite joint works, Petrovic and Tate are modeling one vision of the interconnected future of art: genuine collaboration.

"I was a little hesitant at first," Petrovic admits. "I've worked with some people in the past, and it's always been more working for them than with them, in various degrees." Tate also has experience with less-than-equal partnerships. He stopped planning Apothecarium as soon as Petrovic came on board.

The two men first met at Penland School of Crafts in 1992. Tate - young and hungry for a glass education that wasn't available back then near his home turf of Washington, D.C. - says he trailed Petrovic "like a puppy dog," taking every class he taught. "He trained me to think in that Joseph Cornellian way that he and I both love to do, with cabinets and strange curiosities," he says. (In contrast to Tate's frenetic energy, Petrovic is calm, reflective, more subtle in his humor. "Tim holds me to blame for his methodology," he says, adding wryly that he hopes it's working "because that's a lot of weight to carry.")

As much as they share, however, the two have relied on their differences when working together. Petrovic, based in Essex, Connecticut, identifies himself as an artist who is also a hot-glass sculptor. He creates his idea-driven artwork from blown, hot-worked, and flameworked glass. Tate's expertise, on the other hand, is in the warm glass world - fusing, slumping, and casting. (The Washington Glass School, where he is cofounder and creative director, celebrates its 10th anniversary in June; it is now one of the largest warm glass schools in the country.) As a mixed-media sculptor, he incorporates found objects and interactive media (often video), into his pieces.

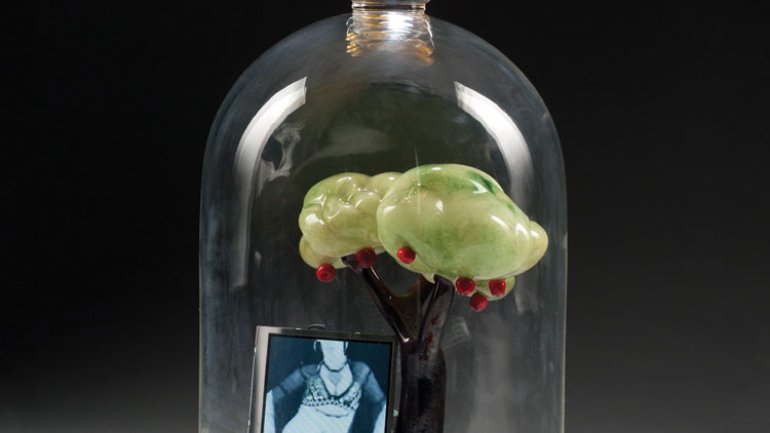

You can see evidence of both men's hands in the joint series. In Cure for Financial Insecurity, part of Apothecarium, Tate's cast-glass dollar sign sits atop the reliquary, which he etched with a cautionary tale about Ponzi-scheme king Bernie Madoff. But it was Petrovic - someone who enjoys tackling a tricky problem - who figured out how to suspend the bingo cage in his blown-glass dome.

As a whole, though, the work is remarkably seamless. Their process, no doubt, helped blend the results. The two began by bouncing nonstop ideas off each other. ("We should all die and go to heaven and do that," Tate says.) They zeroed in on the ills they would aim to treat and how to visually represent their ideas, then split up the workload according to who was best equipped to create or manipulate each element. They mostly worked separately, shipping pieces back and forth - all of the intricate elements waiting to come together when it was time for final assembly.

Two heads are better than one, and, as it turns out, four hands are better than two. "It was nice to not have the full burden of idea generation on my own shoulders, as well as the technical generation of the actual pieces," Petrovic says. "Even when we came up with stuff together, [Tate] would add to it - furthering it along - and then I'd come up with one more minor change, then he could add on top of that. The buildup just seemed stronger than relying on your own experiences."

When Apothecarium was on display at MAD, the museum expressed an interest in acquiring the piece. But Tate and Petrovic had promised the joint work to Heller Gallery for the 2010 Chicago SOFA [Sculpture Objects & Functional Art ] show. To ensure they wouldn't be caught empty-handed, they began work on another collaboration for the gallery. This time Tate, having conceived of Apothecarium, insisted that Petrovic choose the over-arching theme. He came up with Seven Deadly Sins - and the duo started their process all over again, this time freed from the rule of including organic components. While Apothecarium's natural materials give the work a relatively muted palette, Seven Deadly Sins is an explosion of color and good-natured humor.

Look closely: Each piece is loaded with detail. The green finial that sits atop Envy, for example, is a cast-glass likeness of Michael Janis, a tongue-in-cheek poke at an artist with whom Tate shares workspace at the Washington Glass School. The tiny gate is Petrovic's handiwork - a rare opportunity to exercise a long-ago minor in metals, he says. His wife, artist Kari Russell-Pool (with whom Petrovic also has collaborated), lent a hand with the grass.

In Vanity, a small video screen displays the image of all who approach. Peek into this technological mirror and a recorded voice gushes, "You look wonderful. Have you lost weight? You look younger every time I see you." Tate added the video as a special SOFA touch, recruiting a collector he knows (who has "the perfect voice") to record the seductive track.

"Most of the time at SOFA, you can walk in, and across the room [you can see the piece]," Tate explains. "Comprehension is at a distance and immediate. You don't have to dig deep - it's a materiality kind of thing, not necessarily conceptual." Seven Deadly Sins required people to engage a lot more, he says. Drawing in viewers to interact with the work is, arguably, the pièce de résistance of their collaborative process - the sharing of a work that transforms everyone who sees it into an active participant.

While Tate and Petrovic have both returned to their separate pursuits for now, they agree that, given the right opportunity, they would work together again.

"I think we're entering the age of collaborations," Tate says.

Julie K. Hanus is American Craft's senior editor.