Art Is Her Way

Art Is Her Way

When Elsa Mora was a teenager, she made a curious discovery: Her birthday wasn’t really May 8, as she’d always thought, but May 9. Her mother had simply preferred the earlier date because it was Mother’s Day, and made the switch.

“That was an interesting thing for me,” reflects the Cuban-born artist, 42, now living in Los Angeles. What it did was reinforce a feeling she’d had since she was very small: that reality is what you make it.

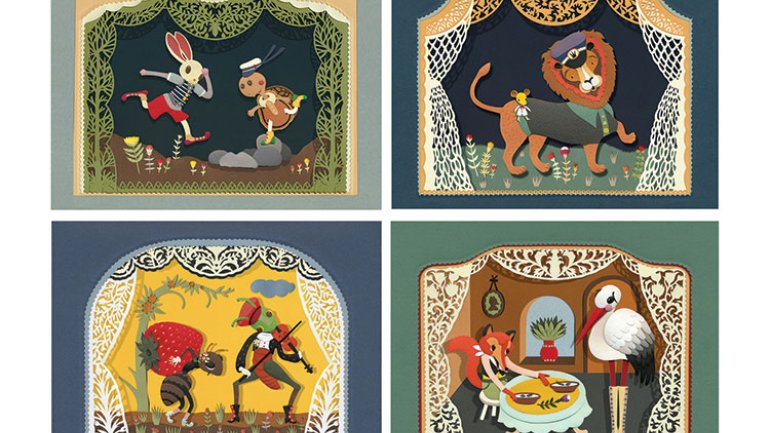

Today, through her art, Mora creates a kind of magical reality, a world of enchanted creatures and supernatural forms, wee folk and quaint little houses, human bodies that morph into birds or lush flowering plants. Her primary medium is paper, which she paints, cuts, folds, and otherwise manipulates into astonishingly detailed pictures and small sculptures, some all in creamy white, others in a full spectrum of rich colors. She embraces any material and format, however, and has done drawings, mixed-media collages, porcelain objects, embroidered jewelry, even whimsical “flower girls” with stem limbs, bloom hats, and petal skirts. She has illustrated books, from a collection of essays on beauty to the cover of Isabel Allende’s novel Eva Luna to a gorgeous pop-up children’s version of the classic de La Fontaine fables. She has designed covers for CDs and smartphones, and a greeting card for the Museum of Modern Art. With all that, she finds time to maintain a lively online presence via social media and her two blogs – one devoted to papercutting (her main craft since 2008), the other an inspirational guide to creative living called Art Is a Way.

“Arts and creativity can make your life better,” Mora says. “I’m all about that. Through art you can see life in a better way, deal with crises, overcome obstacles.”

A dark-haired beauty with a beguiling warmth and an easy laugh, Mora lives in a comfortable, lovingly restored vintage house with her husband and their two highly creative children – a 10-year-old girl, and a boy, 8, who has autism. Her stepson, 21, is in college. In the living room, Mora’s artworks share display space with her son’s elaborate Lego constructions. Out back is the garage with her studio on the second floor – “my little planet,” she calls it. It’s full of her joyful expressions, as well as works with a more somber vibe, obscure images that hint at private tumult and sorrow.

Dark and light, raw and sophisticated, naturalistic and fantastical – the dichotomies in Mora’s art reflect her personality and experience. “I have one foot in a world where everything goes wrong and is really hard, and another in a world where everything is beautiful and happy and positive,” she says. “But I cannot stay in only one. I just have to keep going in both ways.”

Art is her means of navigation. “I think with my hands. That’s what I have done since I was little. And all of this is the result of me needing a way to survive where I come from.”

Mora grew up poor in the Cuban province of Holguín, the fifth of eight children in a family whose members were quirky and creative, yet marked in various ways by poverty, illness, and dysfunction. Her memories are of a hard, volatile environment where children weren’t sheltered from life, or death. When twin sisters drowned in a local well, everyone in the neighborhood saw the bodies laid out, heard the wails of grief and recrimination.

“I was very aware of how fragile life was,” Mora says. “To me, reality was just so real.” Her response was to envision an alternative. “I just always had that in me: ‘There has to be something better than this, you know? And if it’s not there, I’m going to make it for myself.’ ”

So young Elsita drew faces on dried mango pits and styled the little hairs. When it rained, she made mud dolls and dressed them up in bits of fabric. “Cuban people are very resourceful,” she says. “They find things and create something. My brother found a motor from a car and made a fan.” It has stayed with her, this notion that “you can create, no matter what. You can find a way to make something happen.”

She adds that Cubans are, moreover, an unusual combination: poor but educated. “It’s very interesting when someone who can think has nothing. It pushes you in interesting directions, because you have to explore, become even more creative. You have almost nothing in the material world, but you have a lot in your mind. You dream.”

Encouraged by an observant teacher and others who recognized her talent, Mora attended art school, then briefly worked in a gallery before quitting to focus on making art. This was in the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union collapsed and stopped sending provisions to Cuba, which resulted in severe food shortages and widespread misery. Mora fell ill, her weight dropping to 85 pounds. She remembers waking up one morning convinced she’d hit bottom. “I said, ‘This is it. I cannot go on. I have no money, no food. My art is going nowhere. I feel like an animal.’ ”

Then “something amazing” happened. She met an American lawyer living in Havana, who represented Cuba in the United States. The woman loved Mora’s art, and became her patron, mentor, and best friend. Through her connections, Mora came to the United States as a visiting artist at the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work – at that time, mixed-media paintings she describes as “naïve, primitive, philosophical,” with that dark edge – caught the attention of the art world. She had shows at galleries in Chicago and New York, got written up in the New York Times, traveled to Europe. Mora is forever grateful to the friend (now deceased) who opened those doors for her. “I was so lucky.”

With that burst of early success, Mora bought a place in Havana and continued to develop as an artist. Life, at last, was good. She got married, and when that union ended after six years, she was in no hurry to find a new relationship. “I was exploring, changing, learning new things.”

Then, in 2001, her life took another dramatic turn. A friend from Chicago introduced Mora to her brother, a successful film producer, and they fell in love. Suddenly, the young woman who had not even used a telephone before the age of 20 was in Hollywood with her new husband, attending the Oscars, meeting movie stars. While their life is low-key and glitz-free by entertainment-industry standards, the sheer improbability of her journey is not lost on Mora. “Even now,” she says with a laugh, “sometimes I wake up and I say, ‘What am I doing here?’ ”

If anything, her exposure to Tinseltown’s version of the American dream has convinced her that, rich or poor, people are the same everywhere. She has seen great privilege and great artistry up close, but also suffering, “something that’s not about the material. It’s more about your identity, who you are in the world. Here a lot of people live with fantasies and illusions, false ideas about what really matters.”

For Mora, it all comes down to human connection. “The more you know different kinds of people, the more you get to connect all of them, see what’s common,” she says.

“That’s good for you, because it teaches you one single thing. What really matters in the end? One thing; number one: You have to do what you love, no matter what that is. You have to do it, because that is the whole engine of life. If you do that, you just keep going.”

Mora will be in a group show of artists who work with paper, running December 7 to January 4, at Los Angeles’ Couturier Gallery. Joyce Lovelace is American Craft’s contributing editor.