Drawn From Clay

Drawn From Clay

Lonny van Ryswyck and Nadine Sterk of Atelier NL think globally, but dig locally, in their quest to render soulful serving pieces from the ground beneath their feet.

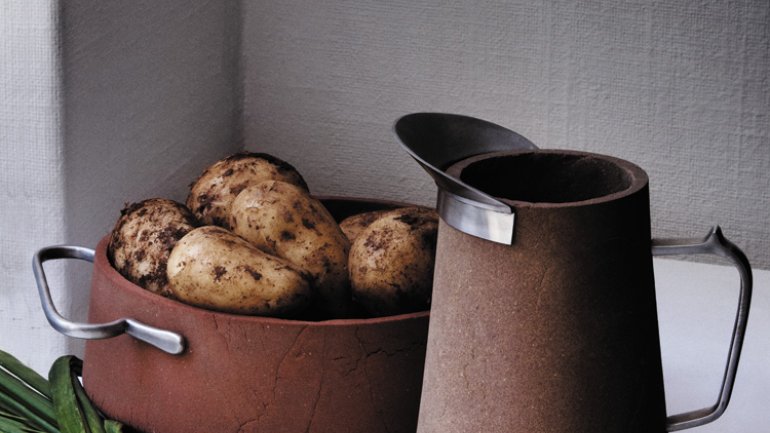

These days, it's likely that you know far more about the origins of every item resting atop your dinner plate - from the fields where the lamb once gamboled to the woods where the mushrooms were foraged - than anything about the plate itself. Designers Lonny van Ryswyck and Nadine Sterk addressed this locavore's dilemma head-on, with their investigation into the farmlands of the Noordoostpolder (Northeast Polder) in the central Netherlands. Gathering samples of dirt from different regions, they created clay and molded serving pieces-what they call Polderceramics-that look at once distinctly modern and plucked from a 17th-century still life. Says van Ryswyck,"We wanted to make tableware so that the vegetables prepared for dinner could be served from vessels made from the soil they came out of." Thus, milk is poured from a pitcher made from the ground where the cows grazed, and a bowl reunites strawberries or potatoes with the soil that once sustained them. More than a poetic conceit, the project - which has been exhibited in London, New York and the Netherlands - illuminates the intimate connections between past and present, farm and table.

For most of their creative lives, van Ryswyck and Sterk bought their clay in a shop like almost everyone else, giving little thought to its provenance. Van Ryswyck's epiphany occurred as a student, when she was in Peru volunteering at the artisans' collective Allpa (which happens to mean "earth" in indigenous Quechua). "There, artists don't buy their clay, they dig it out of the ground, prepare it, dance on it to remove the air bubbles. This is the first time I saw where clay actually comes from-and it was life changing."

On a subsequent trip to Brazil, the two designers observed a self-sustaining Japanese community whose members make their own pots and grow their own vegetables. They determined to return for their graduation project, until a prescient professor at the Eindhoven Design Academy encouraged them to continue their explorations on native ground.

"So we traveled around the country, collecting dirt, with no idea what we'd find," remembers van Ryswyck. "It was like digging for gold." They identified 14 distinct geological regions and fashioned a cup and saucer from each kind of clay. "And when we opened the oven door, it was like a present!" Sterk recalls. "There were all these different colors and textures, depending upon the minerals in the soil." There were buttery yellow pieces, such as those from Brunssum, colored by the chalk that was washed to north Holland when England and France were ripped apart during the ice age; rust-colored cups and saucers fashioned from soil rich in iron oxide; and assorted hues in between.

"When you eat off a plate, you forget that ceramic is made of clay, and that clay is very specific to its location," says Sterk. "In each piece you can read its history and the geological events that shaped it," be it the smooth, shiny brown pottery from Woerden, or the rougher terra-cotta from Gilze-Rijen. Just as a winemaker identifies and exploits the soil characteristics - or terroir - that imbue a wine with flavor emblematic of its region, Sterk and van Ryswyck explored terroir as it relates to pottery, with little thought of commercial gain. "Oh, people did approach us, saying ‘Great, now that we know all the different colors of Holland, we can make this in China and color it with pigments,'" recounts Sterk, a shudder of horror in her voice. "And we said, ‘Absolutely not!'"

Soon after graduation, Sterk and van Ryswyck set up their studio in Eindhoven, and were approached by designers Jurgen Bey and Rianne Makkink to expand the soil project in the Northeast Polder, where they had just established an artist-in-residency program. (A polder is a tract of low-lying land protected by dikes.) Approximately 460 square meters, the area was drained and reclaimed from the sea some 70 years ago to improve flood protection and create additional land for agriculture, and is divided into about 2,000 plots-all neatly cataloged and numbered. "This was a perfect chance to continue our research into regional soils and the links between crops, earth and clay," says Sterk.

When only five farmers responded to their newspaper ad seeking a packet of dirt in exchange for a tile made from the clay, Sterk and van Ryswyck started driving around with buckets and shovels, approaching farmhouses with their graduation project in hand. "The farmers were skeptical that we would be able to make anything from their earth," says Sterk. "They were like, ‘Good luck, ladies!' But they were also very kind, offering us coffee, driving us around on their tractors, and sharing information about the land."

The designers soon learned that the crops had been matched carefully to the composition of the soil. Most of the fruit-pears, apples, strawberries, tomatoes-comes from the southeast, while the sandy, chalk-rich land in the northeast and northwest is used for grazing cattle and harvesting tulips and onions. The heavier middle soil, endowed with iron oxide, supports potatoes, carrots, beets and other root vegetables, and turns a deep orange when baked. And trees grow in the clay-dense soil, which turns a deeper red.

Using a map of the plots and a soil map, van Ryswyck and Sterk selected some 80 farms. "It took us a whole summer to collect the dirt," recalls van Ryswyck. "Friends would ask, ‘Didn't you do this dirt thing already?' But we were really happy. Before, I was not too aware of the seasons, but they helped to shape our work. Summer was for going through the fields, collecting samples, learning the history. Winter was for working indoors with the clay and shaping the project. It's given us a different perspective on time."

Once the dirt was collected, they were ready to make the clay. First draining the soil to a fine powder, the designers dried and sifted it several times to remove the roots, twigs and shells that could cause cracking. Then they remixed it with water and pressed the clay into molds. Pieces include a place setting-bowl, plate and cup-as well as serving vessels and bulb vases, which were influenced by their research into the evolution of dinner sets. "Our grandmothers had a piece for every function, with all kinds of shapes and subtleties. For example, a potato bowl has two handles placed horizontally, but on a soup bowl they are vertical," explains Sterk. "We played with how the embellishment changes the function."

At the same time, they didn't want to create a historical replica of dishes from days of yore, or "end up with some kind of hobby project," as van Ryswyck put it. Instead, says Sterk, they sought to create a link from past to present, "using these basic shapes that are sober and strong, rather like the farmers," but embellished with traditional materials. The ceramic, glass and pewter accoutrements are part of the Dutch decorative legacy and were derived from venerable old factories, such as the blue ceramic feet and handles taken off pieces in the Royal Tichelaar Makkum line, glass chopped off Royal Leerdam Crystal, and pewter spouts and handles removed from old carafes and pitchers.

At the suggestion of their London gallerist, Libby Sellers, the designers ended up blowing the glass directly into the tulip vases, where it protects the porous, unglazed pottery. When the Polderceramics were complete, the studio asked photographer Paul Scala to pose them with local crops, resulting in a series of still lifes that allude to the lighting and mood of 17th-century Dutch painting.

The evocative photographs accompany the exhibition wherever it is shown. "Our primary goal was to tell a story about the farmland," says van Ryswyck, "and give it a historical context." When people see the exhibit, they see the color of the tile, the sugar in a pot made from earth where sugar beets are grown, and a portrait of the farmer who works that plot. They get a new understanding of the land." Every vessel is geo-stamped with the number of the corresponding farm plot. And to make the story about the ground,the history and the region even more graphic, the designers rebuilt a map of the entire Noordoostpolder using the multicolored tiles they made from each area.

To celebrate the project's completion, Sterk and van Ryswyck organized a lunch in the middle of a field, with cubes of hay for tables and fruit crate chairs. Designer friends supplied the drinks, and the farmers brought food made from their land. "It was a super experience bringing together these two worlds, design and farming, that are so often isolated," says van Ryswyck. "One farmer said, ‘When you first came, I didn't believe anything could come of it. People have come before, and we'd never hear from them again. But this is showing me that I am very special.'"

As the Polderceramics project progressed, Atelier nl's previous exploration of Dutch clay was also evolving. "In 2008, Mr. Tichelaar [of Royal Tichelaar Makkum], who had seen our project from school, came to us and asked, ‘What is your dream?'" recalls van Ryswyck, "And we said that our dream is to produce something beautiful and useful out of the natural clay. And he said, ‘This is my dream also!'"

"Of course, 60 years ago, there were clay factories all over the Netherlands," explains Sterk, "extracting local clay and working with it, but now they are the only ones capable of this." The oldest company in the Netherlands, Royal Tichelaar not only produces traditional ceramics, but also fosters creative collaborations with contemporary figures like Jurgen Bey and Hella Jongerius. Under the stewardship of Jan Tichelaar, it has become something of an innovative laboratory for handcrafted custom products, somewhat akin to the American textile company Maharam. Working with Sterk and van Ryswyck, Tichelaar selected six regional clays, formulated a specific protective glaze for each type, and invested in a new machine to process it. "It was very labor-intensive, as they must clean the machine each time so the clays do not cross-contaminate," explains Sterk. Ranging in color from clotted cream to deepest oxblood, each plate, bowl, and cup is stamped with the location and name of the river or sea in Holland that is the source for the clay, as well as for the dominant minerals. With Clay Service now available for sale on the company's website, Royal Tichelaar is working with Atelier NL on a production line of selected Polderceramics, to be available soon.

"The funny thing is, we started out wanting to help craftspeople in other countries, " van Ryswyck says. "And now, with the Clay Service and Polderceramics, we're actually supporting crafts right here in Holland. It's a romantic idea, but also a reality. It makes us very happy."

Deborah Bishop, based in San Francisco, is a Dwell contributing editor.