Masters: Stephen De Staebler

Masters: Stephen De Staebler

Right place, right time.

It’s a familiar phrase, but rarely does it seem as apt as when it describes Stephen De Staebler’s move to the Bay Area in 1958. With a bachelor’s in religion from Princeton and two years of Army service under his belt, the artistic 25-year-old enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, planning to earn a secondary-school teaching degree. He did, but three other things happened, too. He took a figure modeling class, prompting him to get his master’s in fine art. Meanwhile the area’s topography was reawakening a childhood fascination with landscape and terrain. And in 1959, Peter Voulkos showed up.

De Staebler became the charismatic ceramist’s second graduate student – and one of the field’s brightest stars. Like his teacher’s work, “De Staebler’s deconstructed sculptures permanently altered traditional definitions of ceramics and compelled the medium’s critical reinterpretation as art,” says Timothy Anglin Burgard, curator of American art at the de Young museum in San Francisco, which organized “Matter + Spirit,” the first major retrospective of De Staebler’s work, earlier this year.

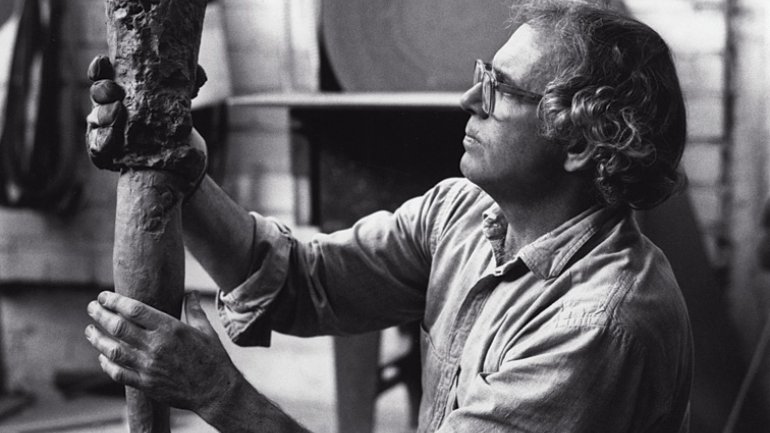

His figurative sculptures invoke deep contemplation. Formed of clay – and later, bronze – many seem to have alighted from another plane, some borderland of body and terrain, of parts and the whole. They represent a tremendous legacy, Burgard says. “Over the course of five decades, De Staebler resurrected and reinvigorated the human figure as a subject, rendering it in a fragmented and incomplete form that was more commensurate with modern existential experience.”

From 1961 until 1967, De Staebler taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, then moved on to San Francisco State University, where he taught until he retired in 1992. Over the course of his career, his totemic sculptures and striking public installations reaped stacks of honors – including two NEA fellowships, and in 1994, election to the American Craft Council College of Fellows, a prerequisite for the Gold Medal, the Council’s highest honor.

“As a sculptor, De Staebler sought meaning in the most elemental of materials – the earth – and, in the process, achieved a fundamental understanding of the human condition,” Burgard writes in the exhibition catalogue. “Keenly aware of our precarious existence ‘between being born and dying,’ the artist nonetheless held out hope for the human beings he shaped with his own hands.”