The Science of Spaces

The Science of Spaces

Arranging a space so that it pleases you is not indulgent; in fact, it’s good for your health. And that’s not just an assertion; it’s the scientific finding of Esther Sternberg, a physician and author of two books on the mind-body connection.

Sternberg’s first book, The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions, sought to explain how modern medicine had dismissed some key ancient truths – “that emotions have something to do with disease, that stress makes you sick, that believing can make you well.” The book was a surprise hit with architects, who praised Sternberg’s vivid descriptions. Their feedback led her to a new question: Can we measure a building’s effect on the brain and the body?

The answers are in Sternberg’s latest book, Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being. If you’ve ever felt your mood brighten – or darken – in a new space, you’ll find Sternberg’s accessibly written research fascinating. We asked her to explain the power of interior design.

In Healing Spaces, you discuss your research on design and well-being. That is a topic that has been studied before, right?

Yes. The scientific inquiry goes back decades, to a study by Roger Ulrich, often called the “room with a view” study. Ulrich proved that patients recovering from gall bladder surgery who had a view of a grove of trees had shorter hospital stays, required less pain medication, and had fewer negative nurses’ notes in their files, compared with those who had a view of a brick wall. That study was extremely well-controlled and has been replicated a number of times in many other settings and under other conditions. It’s been accepted in the health care architecture community for a long time.

What was different about your research?

The question I wanted to ask was: What if we want to gauge the impact of places where people are making a creative product? Can we measure how the brain responds to built space, how the body responds, and get a sense of the effectiveness of the places we are building?

How did you approach your question?

I gathered a group of researchers. We did a study with the General Services Administration (which oversees construction and leasing for all the buildings for the government) demonstrating that we could measure the effects of a new, beautiful, airy, light office space on the office workers who worked there, compared with the dark, dank office space they were working in previously. And we did detect a measurable reduction of the stress response in the new space; even when they went home at night, the workers had a healthier sleep pattern.

How was the drop in stress response measured?

We documented the drop by measuring two things: the amount of the stress hormone cortisol in saliva and the change in heart rate variability that occurs with breathing. An increase in heart rate variability indicates a drop in the stress response and activation of the relaxation response controlled by the vagus nerve.

Does the stress response amount to physical evidence that a place is not healthy?

The stress response is not necessarily a bad thing. It allows you to focus your attention on the task at hand; it gives you the energy to fight or flee. You need your stress response when you need it. The problem is that you get sick if it keeps on going when you don’t need it.

So the lesson in your latest research was that the place where you spend blocks of time, in and of itself, can significantly affect your level of stress.

Yes, and this is an idea that hadn’t gone beyond health care architecture until recently, when neuroscientists and architects began collaborating more. But it applies to homes, office buildings, schools, churches, everyplace.

You mention churches. A cathedral – with its stained-glass windows, soaring music, and incense – is a good example of a space with profound sensory and emotional power. Do you believe people can take cues from sacred spaces to create a calming environment, a serene ambiance, at home?

Yes, absolutely. You can reproduce a healing space, a calming space. But how you do it must be individualized. Some people like bright lights, some dimmer lights. Some of what is calming is learned and cultural; some is biological. Noise is a very powerful trigger to the stress response, more or less universally. Muffling noise helps. And fragrance can be a powerful stress reducer. I have jasmine and gardenia trees on my deck, and the aroma they exude in the summer reminds me of Mediterranean evenings and my mother’s garden in Montreal. That’s unique to me.

You have applied scientific methods to concepts that seem intuitively true – the idea that being in nature nourishes us emotionally, for example. Can science explain why a newly decluttered room feels so good?

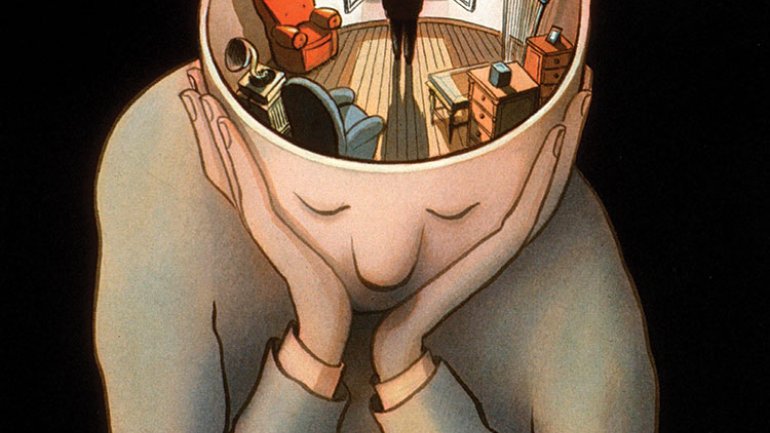

Yes, actually. And this goes back to the stress response. What are the triggers to the stress response? Lots of visual stimuli. Too many trigger a stress response. Basically, clutter turns on the alertness pathways in the brain and causes the brain to work constantly, as it does when you are, say, walking down a busy street or standing in Times Square. Clutter is diverting and distracting. Your brain has to work constantly to decide whether you need to react. Decluttering cuts down on the stimuli that put demands on your brain.

Now, if you are sitting in a room with blank walls, there is no need for your stress re-sponse. Actually, if you are in a blank room, you will probably feel isolated. There is a balance, a happy medium, of stimuli in your environment.

Is there science in the principles of feng shui?

Yes, I think there is some science to feng shui. The idea that you should have the mountains to your back, a vista in front, running water in front of a house, your orientation to sunrise and sunset – all of those things tap into well-being. And some of this is true regardless of culture. Sweeping vistas of nature trigger a particular spot in the brain that is rich in endorphins. It may be that we pay more for a room with a view because we’re giving ourselves a shot of endorphins.

We all have constant intrusions in our lives, with our responsibilities, technology, and so on. To the extent we can go offline, literally and figuratively, and look at a good view, we’ll be better off. If you can’t have a garden outside your window, have it on the desktop of your computer or on your wall. Take a few moments to look at it.

Do you see a connection between your findings and the benefits of looking at – or, for that matter, making – art?

Yes. It’s important to remember that the arts are not a luxury. From time immemorial, since human beings made cave drawings, they have created art. I think it’s what sets us apart from animals. Some birds create nests that are beautiful, but to purposefully create something beautiful for the sake of making it beautiful, that is human. Seeking beauty must have some survival value in a world that is frightening and full of disease, death, and stress. It brings us a small period of respite.

When my daughter was a teenager, we took an etching class together at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where we lived. It was hugely stressful to pick her up after school and slog through traffic every Tuesday night to get there. But the class was this island of peace, and we were just focused on the work that we were doing. The world could be falling apart around us – and because of some stresses in my life, it felt like it was – but we were focused.

How does the act of making art affect the body?

Looking at art is one thing; creating it is different – an almost meditative experience. I’d go so far as to say it is a meditative experience. Focusing on the moment puts us in a state of mindful meditation. And when you’re done making, you have the pleasure of looking at what you’ve created and enjoying it. It’s a double whammy. It has a beneficial effect on the brain pathways, the reward pathways, and the relaxation response counters the effect of the stress response.

What would you tell someone who wants to create a living space that feels good?

There are some universal principles. Too much or too little of anything is not good in biology. Very bright lights aren’t good, but indirect, full-spectrum lights are restful. And the color green is effective: views of green and plants. Bringing green in, having views of green, is universally beneficial.

But much of what is nourishing in a space is personal. Tap into your memories; think about what it is that will bring you to that peaceful, healing place. Tailor it to that. I have objects around – paintings my mother made that I particularly loved in childhood, my grandmother’s teacups, which remind me of having tea with her on a sunny afternoon. What brings you to that place in your past?

Monica Moses is American Craft’s editor in chief.