In Tune

In Tune

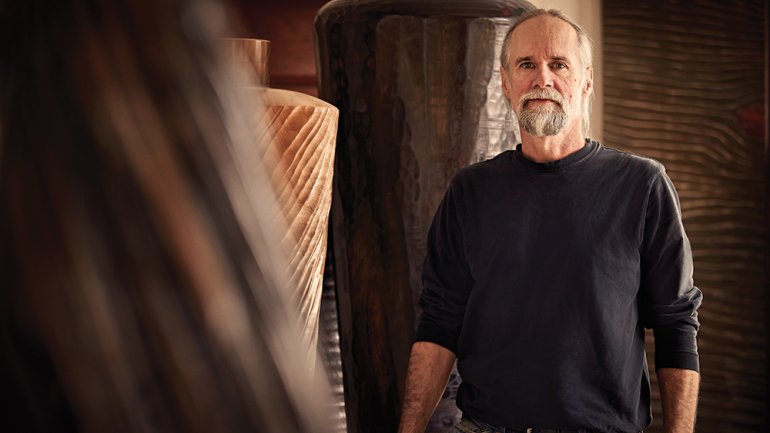

Michael Bauermeister’s wood sculptures capture the wonders of the natural world he loves: pebbles on the shore, a twist of vines, that first exuberant burst of growth in spring. Waves of grain, ripples on the water, and canopies of leafy tree branches come to life on the soulful surfaces of his carved vessels and wall panels and seem almost to move if you gaze long enough. Their rich colors range from forest greens and the deep browns of fertile soil to orangey golds and yellows so citrusy you can practically taste them.

These are works about land, specifically the Missouri River bottoms, a flat expanse of corn and soybean fields, big skies, and long horizons. It’s where Bauermeister (the name, fittingly, means “master farmer” in German) has lived, worked, and taken much of his inspiration since 1987, in the rural town of Augusta, Missouri.

“It’s beautiful, very quiet, a good place to get work done,” he says of the spot, which is about 35 miles west of St. Louis – close enough that he can easily get there for an occasional dose of city culture or to pick up salvaged wood, his raw material, from the “urban logger” who supplies him. Bauermeister maintains his studio in a 1920s building that was once a general store – about all that’s left of a tiny, long-gone town called Nona. The place still has the original shop counters and shelves, and “kind of feels like one big tool,” he says. “I feel so comfortable working in there. Every inch of it is like an extension of my body at this point.” Right past the front runs the scenic Katy Trail, where he rides his bike almost every day.

On a rise within walking distance of the shop sits the wood-frame house Bauermeister built, its interior replete with imaginative uses of old doors and recycled wood and stone, and lots of big windows overlooking the landscape. He shares it with his wife, artist and musician Gloria Attoun Bauermeister, and their 13-year-old mutt, Ellie. High-school sweethearts from nearby University City, the two married shortly after Bauermeister’s graduation from Kansas City Art Institute in 1979 (where Bauermeister settled on wood as his medium), and have two sons (Ben, a professional drummer based in Memphis, and Zac, a college student in Seattle).

Together the couple performs in the Augusta Bottoms Consort, a four-person country-folk ensemble; his instrument is a dobro, while she plays guitar, banjo, and mandolin. His parents, retired Lutheran ministers in their 80s, come to every gig and sit in the front row. Along with biking, music is an essential outlet for Bauermeister, who, after a long day in the studio, likes to “relax, drink a few beers, and play some country songs with friends.” The high point of his week is a Tuesday jam session with a bunch of local guys at the studio of another old friend from high school, glassblower Sam Stang.

It was Stang who in 1991 convinced Bauermeister, then mostly a maker of custom furniture, to join him as an exhibitor at the American Craft Council’s Baltimore show. Bauermeister brought some wood bowls he’d been carving as an experiment – the genesis of what he’s doing now – and people liked them. Within a few years he had transitioned to sculptural work exclusively, “and it just grew from there” – literally grew, to the point where tall, somewhat figurative vessels have become his signature. His first large piece came about “at the suggestion of my son, who was about 8 at the time, to make one as tall as he was. So I did. Then I had to make one as tall as I was,” he recalls. “I really like working large. That human scale is what I keep coming back to.”

To build a vessel, Bauermeister stacks and glues together layers of wood, hollowing out the inside as he goes. He then sculpts the whole thing into a free-form shape, or turns it on a lathe if he wants it perfectly round, or uses power tools to cut away sections if he’s making an openwork piece. He’ll then gouge and carve the surface by hand, creating pattern and texture out of countless tool marks: “I like the energy that went into the making of the piece to be visible.”

Finally, depending on the look he’s going for – grainy or smooth, variegated or solid, translucent or opaque, muted in color or highly saturated – Bauermeister will sand, paint, stain, lacquer, and polish as needed. The process is laborious and takes lots of time (just how much, he “couldn’t estimate and probably wouldn’t want to know”), but some 20 years on, it still gives him endless creative satisfaction.

Yet underneath all the effects he’s mastered, Bauermeister notes, “I’m trying at the same time to get that woody feel to come through.”

His sculptural wall panels – carved like the vessels, with similar colors, textures, and depth – are a newer focus for the artist. “I’m really interested in going larger with them,” he says, and recently did seven panels, each 8 feet high, for a Phoenix hospital lobby. The format has opened up a new avenue of expression for him. Sometimes he’ll compose simple fields of color; other scenes are more representational, depicting the patchwork of real fields around him and the changing colors of the landscape as different crops are planted and grow.

These days Bauermeister is thinking about “ways to build a little more narrative into my work, especially the wall pieces. To somehow make a statement, get a little conversation going,” particularly about the effects of climate change he observes lately in the environment. No doubt he’ll mine this vein with his usual keen eye and sensitivity, fully in tune with his surroundings.