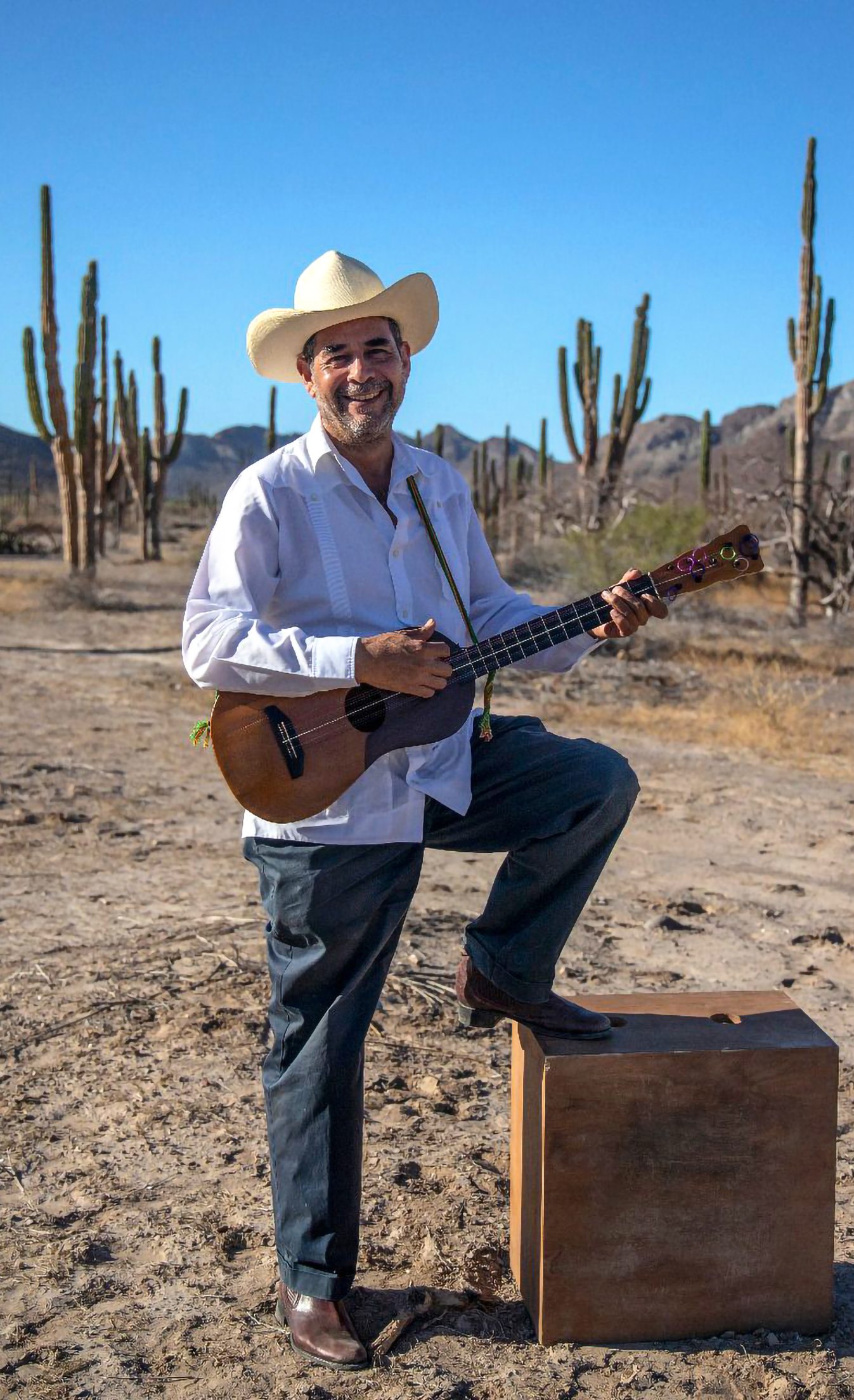

Gilberto Gutiérrez started making instruments out of necessity.

In the late 1970s, he and like-minded musicians became passionate champions of the music and dance known as son jarocho—one of several genres born in Mexico’s rural Gulf Coast region that includes Veracruz.

Gutiérrez and his bandmates in the group Mono Blanco scoured remote villages to record old-timers singing and playing traditional sones. Then they launched workshops and meetups where knowledge was transferred to young people eager to learn.

“They had enthusiasm, but there were no instruments,” Gutiérrez says of his students through a translator. “So that’s why I decided to go learn [to make them] in the summer of 1980.”

Among the instruments Gutiérrez hoped to construct was the guitar-like jarana, which, built in various sizes, forms the backbone of the rhythm section. Unlike a guitar, glued from various wooden parts, a jarana is carved, body and neck, from a single block of wood.

“That’s why I think of the jarana as a sculpture,” he says. “It has a lot of detail, especially where the neck and the top meet, and requires a certain skill. And visually, it has to look good.”

Gutiérrez learned this sculptural art in the workshop of Don Quirino Montalvo Corro, then in his 80s, who built jaranas by hand using traditional techniques. In the years since, Gutiérrez has taught the craft, largely as he learned it, to hundreds of students across Mexico and the United States.

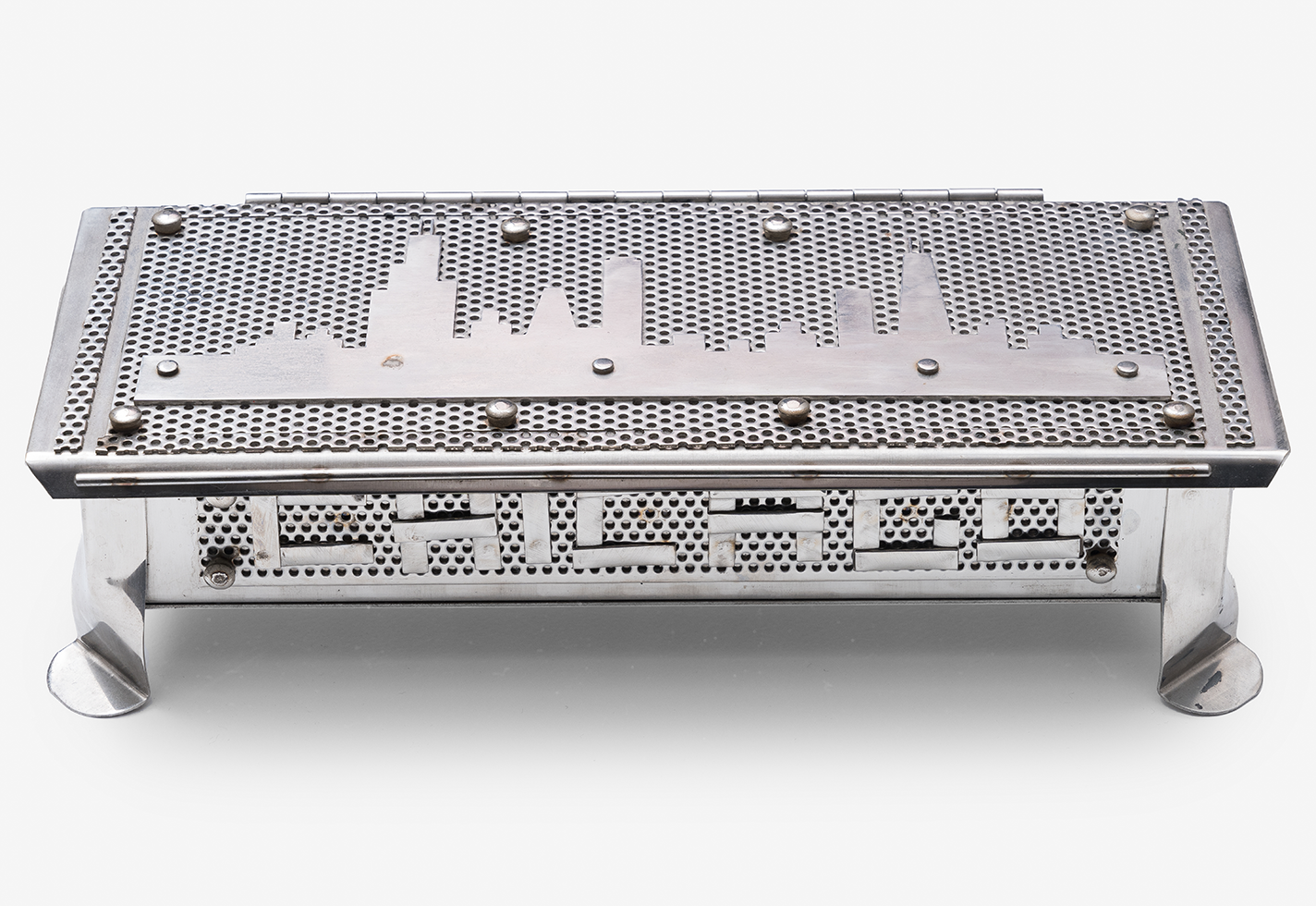

Dancers perform intricate foot patterns on the tarima, a percussive, hollow platform.