An imposing double chest of drawers stands atop four cabriole legs. So far, so standard for a style of dresser that first appeared in 17th-century England and remained popular there and in the United States throughout the 18th century. In the hands of sculptor and woodworker Stacy Motte, however, this highboy is a jumping-off point for a trenchant examination of imperialism, land speculation, and slavery.

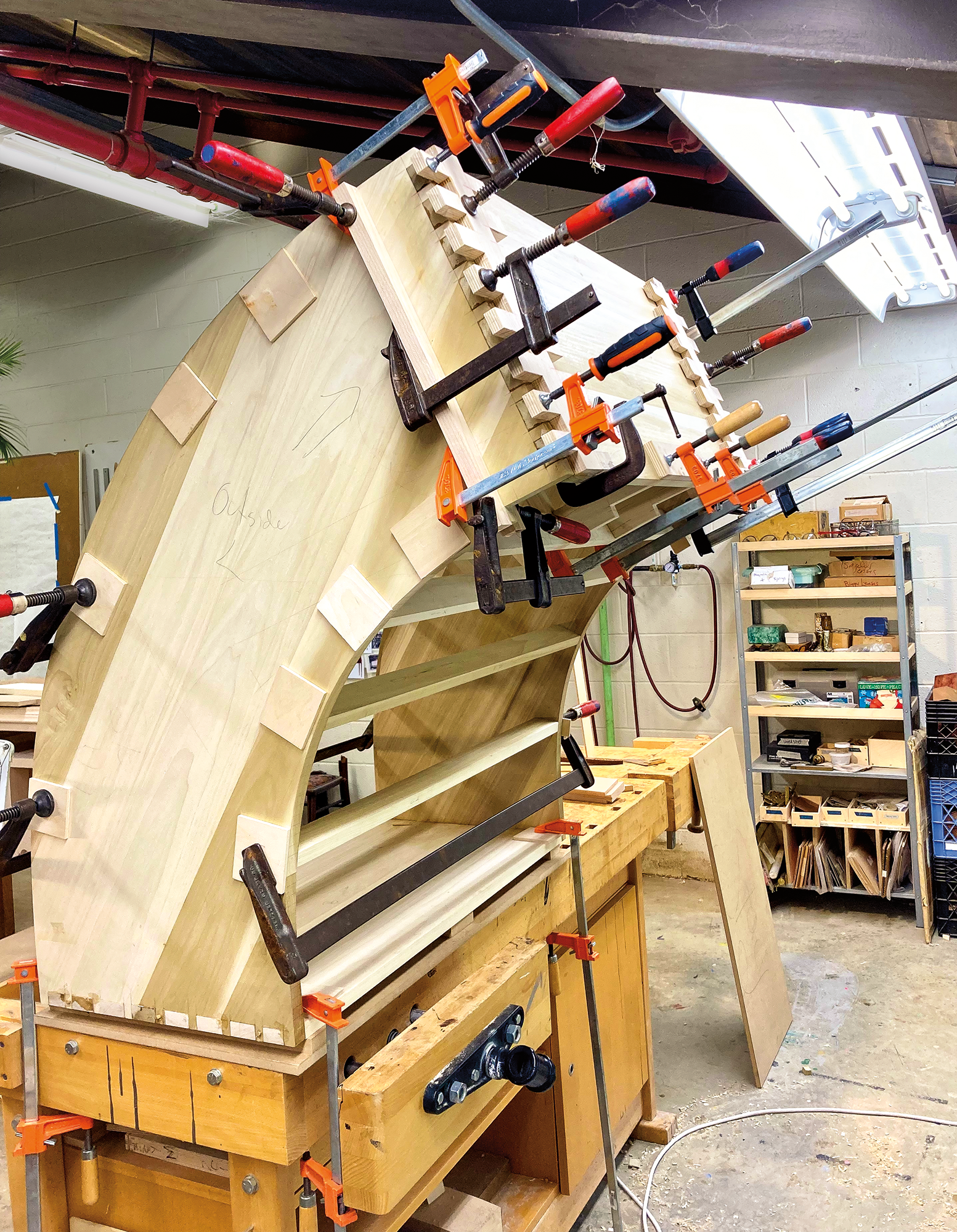

The bureau itself is massive—highboys often measure seven feet tall—and the Chippendale batwing drawer pulls are appropriately ornate. Unlike a working highboy, though, Motte’s version bows forward at the top, creating a feeling that the entire structure is at risk of tipping over, a sensation heightened by a light-skinned feminine hand that appears out of a bottom door and pulls a top drawer down, like an outstretched tongue. The effect is at once elegant and defeated—a sad giant who has lost a battle.

Titled Adventures in Highboy Land, it’s an impressive accomplishment, especially for someone who didn’t consider herself an artist until she was 30, when she enrolled at California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco to study photography. Dismayed by the high cost of frames, Motte enrolled in a woodworking course so that she could make them herself.

“I realized that I was much better at thinking through ideas and communicating them in three dimensions,” says Motte, who, while at CCA, discovered almost instantly a love for cabinet making. “You can load them with information and stories, and they just have all these purposes in our lives.”

After completing a degree in photography, Motte spent an additional two years at CCA getting another BFA in furniture design. Upon graduation, she was selected for the prestigious Windgate-Lamar Fellowship from the Center for Craft in Asheville, North Carolina. That honor was followed by an MFA at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, which in turn led to residencies at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and the Appalachian Center for Craft at Tennessee Tech University, which is where she completed Adventures in Highboy Land.

A portrait of Motte taken at the Heritage Square Museum in Los Angeles.