The “choreography of shape and space” that defines the vessel, in the words of ceramic artist Syd Carpenter, informs our relationships with the world. The spaces we inhabit or traverse mediate our sensory engagement with it. Through the vessel’s walls we absorb and digest truths, which settle and mingle with new encounters. The resulting mixture, comprising sense and experience, could be called memory.

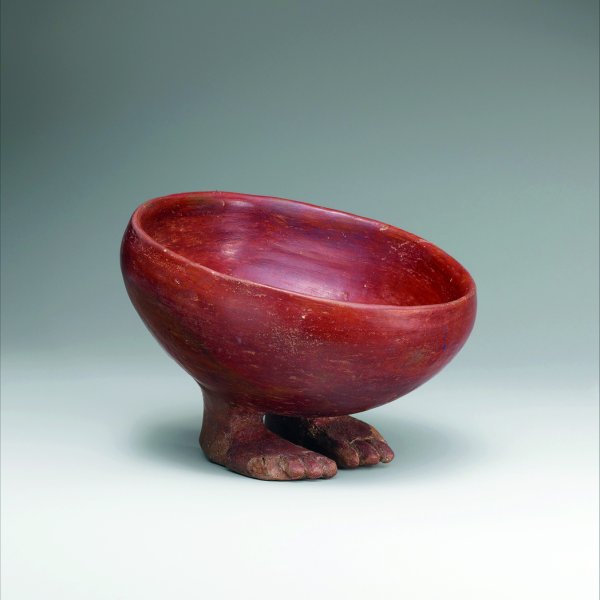

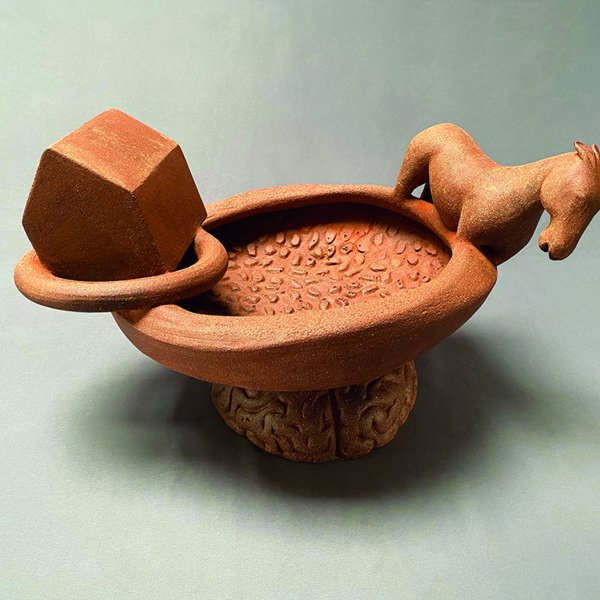

In Carpenter’s newest series, Farm Bowls, she restores the stories and memories that have been erased from lands that were owned and cared for by African Americans. The bowls are precariously balanced (many on representations of brains, the vessels of memory) and bear the weight of farm animals, implements, homes, fences, and other tools for tending and cultivating land. The names of the landowners are carefully inscribed on the works. For Carpenter, an artist for whom the vessel provides a rich lexicon of signs and ideas, the bowl is a reclaiming act designed to hold the truths of the past for future stewards who will keep the land fertile and nourished.

The vessel keeps, holds, and remembers but remains transitory. While this is yet another reason for its alignment with the human body, it also reflects the idea of the body’s contents moving between worlds. In video artist Bill Viola’s Going Forth By Day (2002), a man is shown floating away in a small barge while two people on the water’s edge witness his departure. Viola based this five-part work on the Egyptian Book of the Dead; its wordless elegance, dreamlike pace, and layering of mythologies on a contemporary scene remind us—through this symbolic use of the vessel—how informed we are by the ancients and their understanding of universal phenomena.

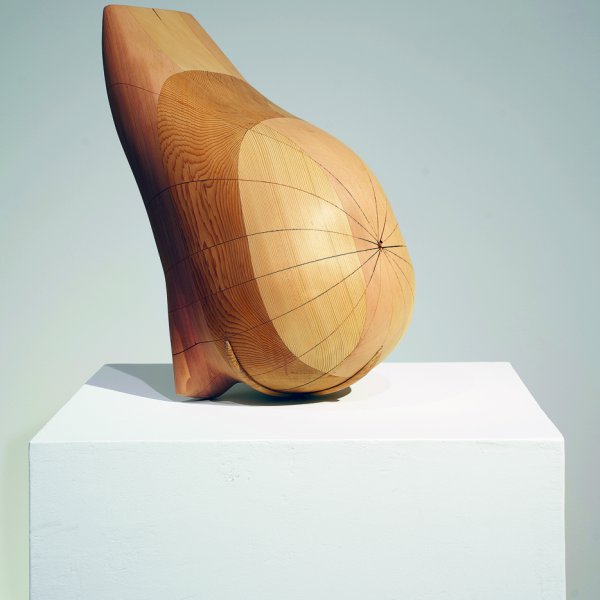

Jack Larimore’s Sycamore Story (2021) relates a similar theme with poetry and reverence. In it, a boatlike form traverses the protective sheath of sycamore cambium that encircles it. Is it departing or arriving? According to the artist, a vessel is a container for living things; wherever they are on their journey, the living materials, both contained and containing, tell a story that reaches the most primeval part within us all. That part knows what’s going on, even if the concerns of our time have dimmed its acuity.

Sometimes there is tension between the built world and the natural world. The depiction of a vessel traversing between these realms reflects the complexity of fears and tensions that accompany us as we live our lives. The vessel brings a sense of safety; encompassed by it, in these re-creations of wombs, we gain confidence to confront the unknown, releasing ourselves to the next world.

“The vessel has entered human consciousness from very early times as a vehicle for important and sacred ideas, often becoming a repository of value, of collective memory and experience,” wrote curator, educator, and potter Christopher Tyler. We invoke its form again and again, in the realms of our imagination as well as our quotidian lives.

In considering the vessel’s contemporary relevance, I’m reminded again of the design of Lusail Stadium. Its beauty and functionality belie the dark lethality that was invested in its construction, during which many workers died. This dichotomy shifts our focus to the most vulnerable in society. Who has access to the protection of the vessel?

sacrificed for it? And how can we draw from the comforting traditions established around the vessel, such as holding and nurturing, to build equity and create space for all people?

The vessel, as both an ancient and modern form, will not let us forget or ignore; it calls to and magnifies our humanity, and we look to future artists, makers, and consumers to answer these questions in time.

Jennifer-Navva Milliken is the executive director and chief curator for the Center for Art in Wood. Prior to her arrival at the Center, she served as an embedded staff member in international art museums, as an independent curator, and as the founder of a cross-disciplinary art space. Her exhibitions have been presented in museums, art fairs, galleries, and unconventional spaces, and her writings have been included in exhibition catalogs, anthologies, and publications that investigate and critique the intersecting fields of art, craft, and design. With a global perspective, honed through a life split between two continents, she is driven by the extraordinary power of the arts to challenge preconceptions and bridge divides.