America has historical amnesia.

Citizens today often struggle to face uncomfortable facts of history, such as the genocide of Native Americans, their internment in residential boarding schools, and slavery. The absent and distorted narratives have many Americans singing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” while many others grapple with historical and contemporary traumas that have yet to be properly addressed. We can’t get to reconciled if we skip all the reconciling; we can’t get to healed if we skip all the healing.

We all lose when we lose sight of our history. We are all products of that history whether we see it or not. So losing narratives means losing ourselves, in a way. America and many of her citizens are having an identity crisis.

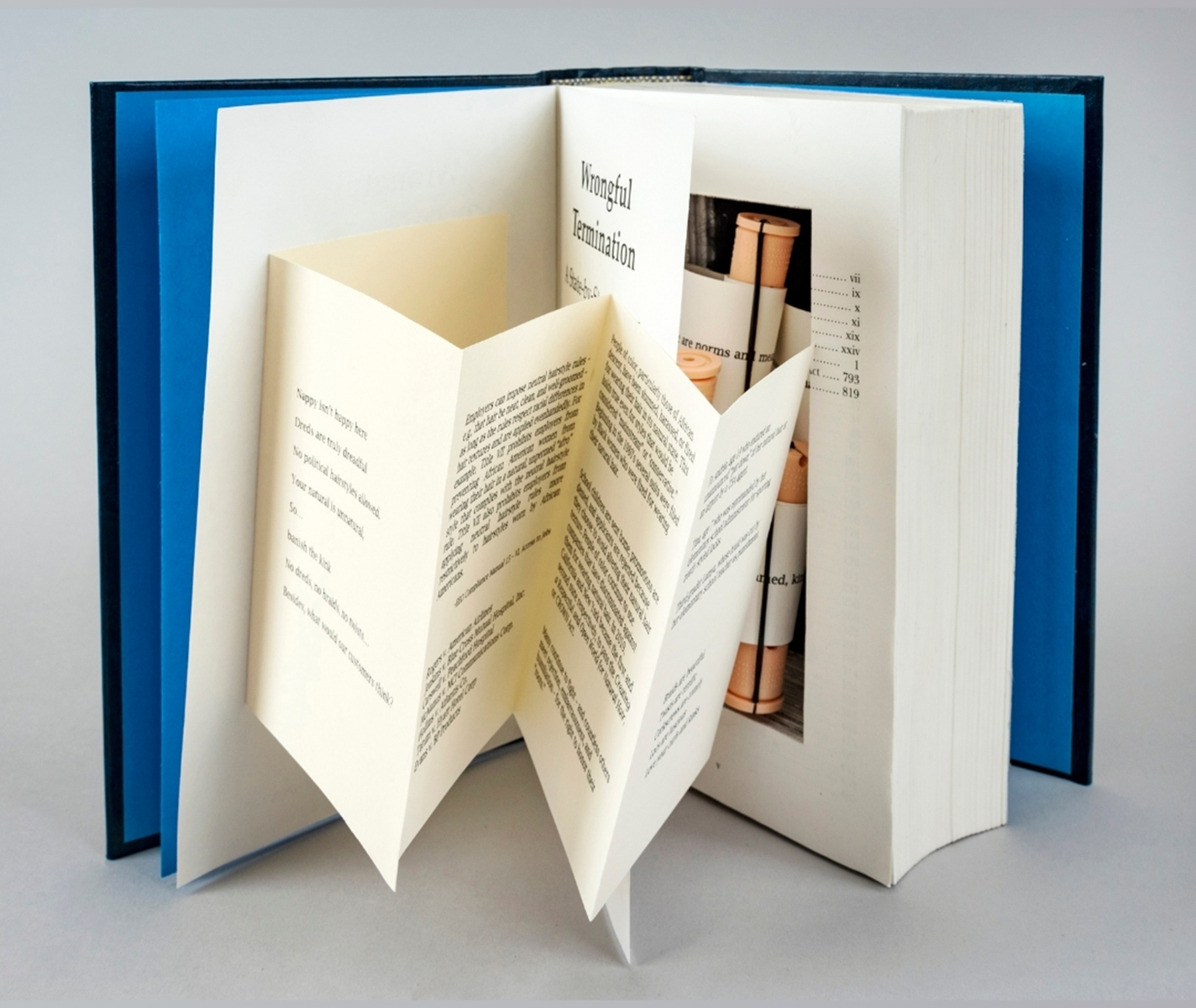

Art and music have a special power to transcend our differences. We speak to one another in these media with and without words; and in these fertile environments, healing can grow. In Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas, Jennifer Raff shares that Native American DNA has been separated from that of other humans for around 35,000 years. At the time of Columbus’s arrival, there were 100 million Indigenous people in the Americas; the entire population of Europe was only 88 million. This continent was not home to scattered bands of roaming nomads in the wilderness, but to numerous different sophisticated and populous cultures. The art of Native Americans predated all others in this place, has been sustained throughout America’s history, and continues to thrive today. It is timely and necessary that we reenter this space. It can unlock a deeper understanding of our history and identity, and help unlock the healing we all need.