Most quilts begin with a pattern. Cait Nolan’s quilts begin with a seed.

Each spring on her small farm in Williamstown, New Jersey, Nolan plants a palette of color: the deep blue of indigo, the sunny yellow of weld, the rich red of madder, the dusky purple of Hopi sunflower. Autumn adds the tannin-rich browns and blacks of foraged black walnut, acorns, and tree barks.

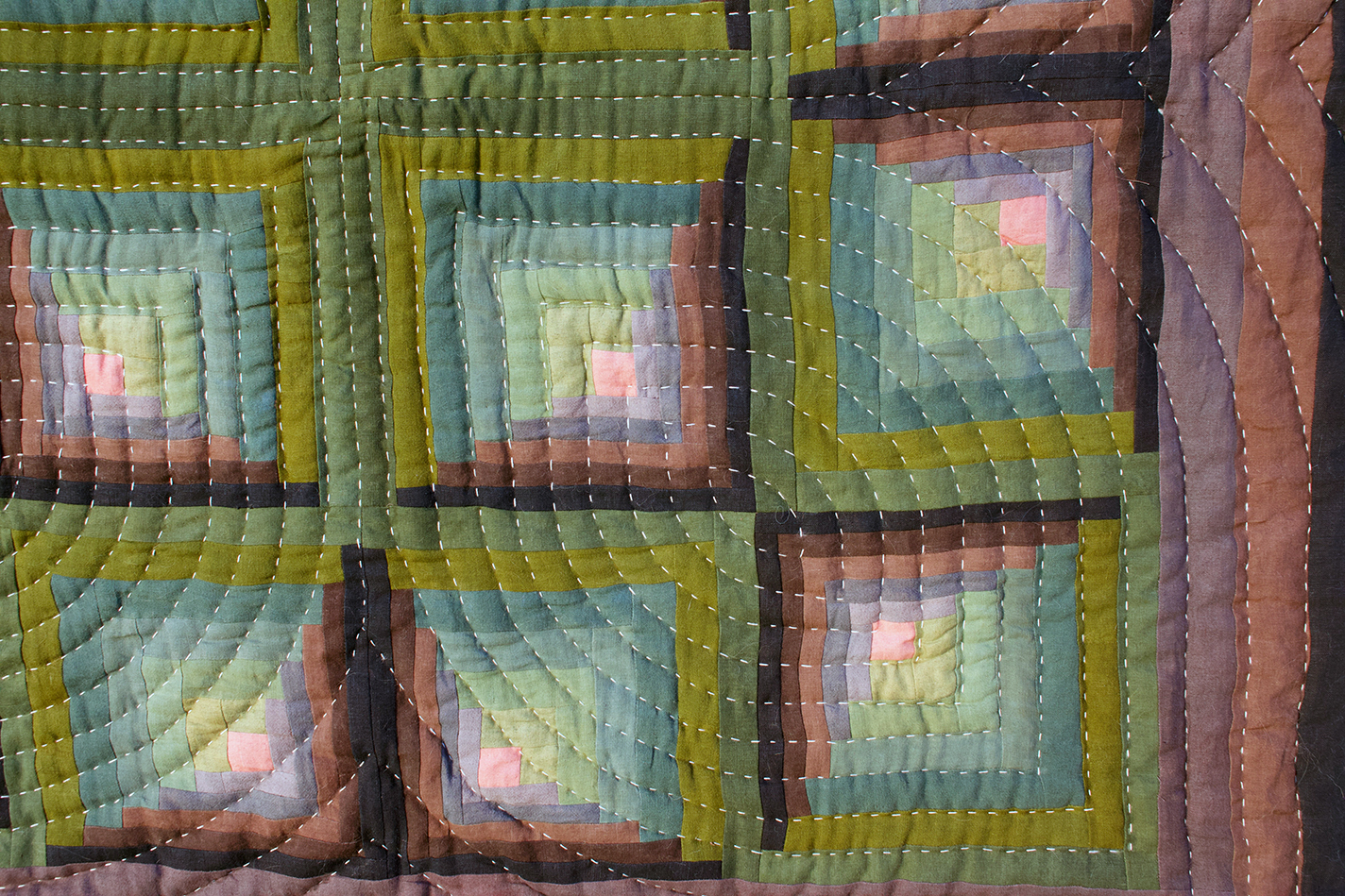

From June to October, she dyes her dwindling stash of secondhand linen with no particular quilt design in mind. In a dye world often focused on uniformity, Nolan embraces unpredictability. She layers and overdyes to build a library of hues and values. Come winter, she turns to her shelves to see what the year has given her. Then, in the dark and dreaming months, she begins quilting.

Nolan with the Japanese indigo plants she uses to create a deep blue dye.