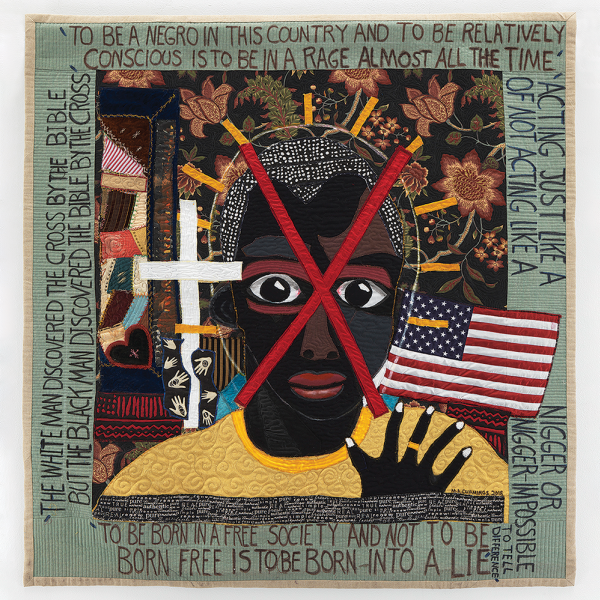

Wilson began her practice in the 1970s after studying sculpture and textiles while receiving her MFA from the California College of the Arts. Her artistic lineage lies with the post-minimalists (including Eva Hesse and Robert Morris); feminist artists (such as Faith Ringgold and Judy Chicago); and fiber artists Magdalena Abakanowicz and Claire Zeisler, who used rope, thread, and cloth to challenge minimalism’s rigidity and sculpture’s traditional material categories, while critiquing sexism and racism.

Wilson’s early works incorporated faux fur cut in irregular shapes and painted with oils to resemble freshly flayed skin; and synthetic felt cut, stitched, and painted to replicate animal hide. In the late 1980s, Wilson threaded human hair into cloth works she calls “material drawings” or “physical drawings,” exploring the territories of hair’s eroticism (when attached to the body) and the distaste it stirs (when detached from the body). She exhibited her stitched constructions during the 2000 solo exhibition Anne Wilson: Anatomy of Wear at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. That work grew into Topologies for the 2002 Whitney Biennial, in which a diminutive landscape and an architecture of pins and netted lace sprawls across fields of white.

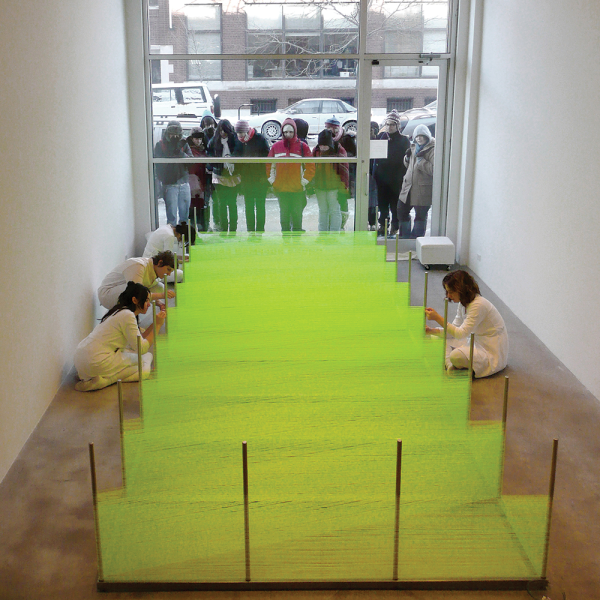

Out of this work emerged Errant Behaviors (2004), Wilson’s stop-motion animation of Topologies, in which lace fragments danced to found sounds by Shawn Decker. In 2008, at Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago, Wilson presented three interrelated works: Wind-Up, a series of performances including Walking the Warp, a five-day experience of walking, counting, rolling, and winding as Wilson and nine collaborators built a 40-yard weaving warp on a 17-by-7-foot frame; Notations, Wilson’s photographs of motion sequences based on a system capturing the repetitive, rhythmic, and cumulative hand gestures underlying winding, knitting, and crocheting; and an iteration of both works called Portable City, consisting of 47 steel and wood vitrines holding thread or filament structures under tension, suspension, compression, or collapse.

Since 1979, Wilson has taught in the fiber and material studies program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; she is now professor emerita. She has written and lectured extensively on the history of textiles. She was inducted into the 2000 ACC College of Fellows, is a United States Artists Distinguished Fellow, a Fellow of the Textile Society of America, and has received awards from the Driehaus Foundation, Artadia, the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, NASAD (citation recipient), Cranbrook Academy of Art (Distinguished Alumni award), the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Illinois Arts Council. At the Museum of Arts and Design, Wilson recently launched the MAD Drawing Room, in which visitors can explore her personal archives of lace and open work textiles.

Wilson’s art is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, among others.

For more than 30 years, Wilson’s practice has infused craft with a singular fiber-based aesthetic impulse, while engaging with sociopolitical frameworks that dictate and inform the production of her work. “Although I’ve worked between drawing and sculpture and performance, my artwork has always been grounded in a textile language,” she told Northwestern Art Review.

“Textiles are carriers of skill-based knowledge, concepts, and expression, aesthetic tradition, and familial and cultural histories; they can express both personal and cultural narratives. Today, textiles are a robust participant in contemporary art.”