All Together Now

All Together Now

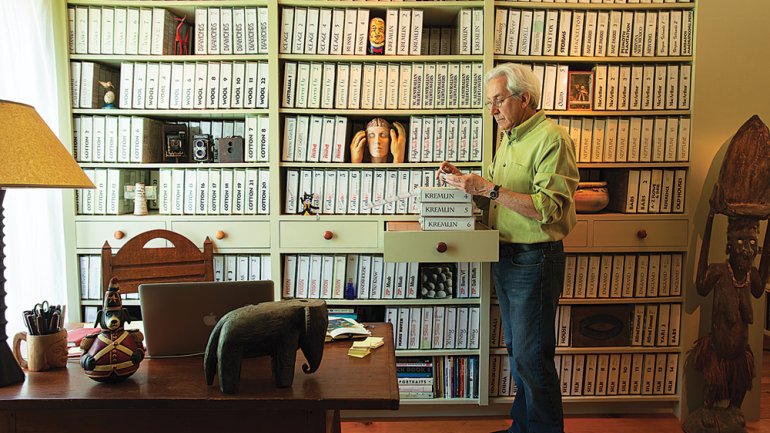

Cary and Barbara “Babs” Wolinsky and their son, Yari, live in a magical compound in a quiet community near Massachusetts Bay, south of Boston. The original house dates from 1840, complemented by a huge new studio that looks both ultra-modern and ancient. Other structures such as potting and storage sheds and an outdoor oven dot the property. Here the three work together on artistic projects blending Cary’s still photography, Yari’s films, and Babs’ graphic design work.

Collaboration seems to be a watchword in your family, both in your daily tasks and the buildings where you live and work. Explain the nature of your collaboration.

Cary: We’ve always worked as a family. We kid that Yari started working when he was 6 months old and we took him to China when I was on assignment on a story about silk for National Geographic. It was 1982, when China was just opening up.

Babs: The Chinese loved holding a blond, blue-eyed baby. They passed him from person to person up and down the cars of a train we took from Hangzhou to Shanghai. We weren’t worried at all.

Cary: Yari continued to travel with us and took on other roles over the years. Once he graduated from college, where he studied film, he added that skill. Babs does the graphic design work, as well as creating her box assemblages.

Your current collaboration is a film about the creation of an almost full-size replica of the 17th-century Gwoz´dziec wooden synagogue in Poland, which was destroyed in World War II. How did that come about?

Cary: Our friends Rick and Laura Brown, sculptors and teachers at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, undertook the replica as a project driven by students, creating many local workshops throughout Poland over the past few years. We started the film in 2006 but really committed to it after Babs ran a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2012 to raise funds for it.

Yari: My father and I neatly divide the logistical (him) and technical aspects (me) between us. There is a much blurrier division when it comes to creative decisions. For this film, though I am getting the credit as director, we don’t ever think of there being a hierarchy of artistic vision. One or both of us may develop concepts for production in the field. Sometimes I take the lead in editing, but we are always talking and showing ideas to make sure it is achieving something we both find elegant. We plan to have the film finished in time for the October opening in Warsaw at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, where the synagogue will be the centerpiece.

Can you explain the evolution of your house?

Babs: I bought it in 1977, before we were married. It was probably originally an outbuilding of a farm. It was so small that people in town called it the “doll’s house.” I wanted a place that was untouched so that I could create what I wanted from it. What is now the pantry was originally the master bedroom. I think if they’d had a full-sized bed in it they’d barely be able to squeeze out of it. We’ve added on in stages over the years; Cary and I have been inspired by the places we have traveled to. The first addition was after a trip to the Virgin Islands, where we had the opportunity to stay in a house with an open living space – you could get out of bed, walk over to the pool, and swim to the outside garden. We didn’t build the pool, but we did build the open living space.

Cary: Everything you see here is a Babs inspiration. I was on the road for National Geographic six to eight months a year, and she did it all.

The rooms are filled with everything from textiles to sculpture to a free-range black rabbit. Where are all these disparate items from?

Cary: Many of the textiles stem from the five stories on color and textiles that I did for National Geographic. They took us to 25 countries, including China, Russia, Japan, Australia, and New Guinea. Over the years we’ve brought back things – woven tent sections from Sichuan, China, weavings from Turkey and Morocco, silk from India, sculptures from Africa and New Guinea, and much more – that embody the story of our lives. Unfortunately, they also included a felt carpet from southwest China that turned out to contain wool moth larvae, which we didn’t realize until months later when we suddenly had a house full of wool moths.

Babs: But the rabbit is local. I went to buy corn one day and came home with a baby rabbit instead. I don’t like animals in cages, so Sumi has free rein in my office during the day. She loves to shred the recycled paper for me and keeps me company.

Part of the interior looks like a jungle because of all the plants –some that flower at night, many with a strong fragrance. How did this come to be?

Babs: The conservatory just off our bedroom came after a failed attempt to use solar greenhouse windows to heat our living space. The original sloped windows leaked, so we replaced them with two gables, one of which we pushed out to create the conservatory. I come from a family of gardeners. When I moved to Boston years ago I brought one houseplant with me, which I still have. It has taken years to find the plants that do well in our space, but those that do, thrive. And at the end of the summer, when I bring them all in from the outdoors, they do become a jungle.

Tell us about the design of the studio, an astonishing and beautiful building, and why you entrusted it to three very young men.

Cary: We planned for a while to add a studio to the house, but we weren’t inspired by the drawings that established architects gave us. Wyly Brown, Rick and Laura’s son, was a student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and wanted a crack at it, so I gave him a two-page, two-column set of design and technical requirements. Wyly designed a building separate from the house, primarily supported by two large tree trunks from our property. I wanted a building with a high ceiling and lots of interior space that wouldn’t look overwhelming from the outside. Wyly solved the problem by creating a curved roof laid over long, curved timber trusses. Not only did he design the studio, but he wanted to build it as well! He’d more or less grown up with a hammer in his hand, so we gave him a chance. He chose two sculptors, Nick Doriss and Jason Loik, as collaborators, and Yari joined the team as well. At the time I was working on a story in Asia and was very interested in Japanese stone and wood architecture, and Wyly, whose wife is Finnish, loved Finnish wood architecture, so we ended up incorporating aspects of both. Practically every part of the building is specially crafted, from the trees and trusses to details like Nick’s hinges and Jason’s latch on the giant front door, the steps that look like butcher blocks, and the imaginative outside lamps. It’s a wonderful and flexible workspace.

Babs: The studio is much more than a building. It is a constant reminder of an incredible time in our lives. Wyly, Jason, and Nick joined the three of us for lunch every day, where we not only discussed the evolving construction but much more about art, music, and world events – we shared our stories and our inspirations. And we had a lot of fun.

Christine Temin wrote for the Boston Globe on dance and visual arts for 27 years, leaving eight years ago to become a freelance writer.