Anne Cole

Anne Cole

When she was a seventh-grader in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Anne Cole first played a cello, which she borrowed from the school. “This one was all carved up and scratched up,” she says, “just completely vandalized.” Disheartened that anyone would treat an instrument this way, Cole brought it home over winter vacation, took it apart, and revarnished it.

“From then on, I told my parents that I was going to be a violin maker,” Cole remembers. “But I had no idea how.”

The “how” involved years of informal study: a how-to book from the local library, a violin-making kit given to her for Christmas, and her piano teacher’s next-door neighbor, who let Cole watch as he made instruments. She graduated from the University of New Mexico as a music major “because that was the closest thing I could get to violin making,” earned a master’s degree in cello performance at UNM, and in 1967 began teaching, moving from city to city as opportunities became available for her and her husband, David, also a music teacher. In a kitchen in Los Alamos, New Mexico, Cole finished her first instrument, modeled after a viola by Italian Renaissance master Gasparo da Salò; she had started it back in ninth grade.

So began a career that has lasted more than four and a half decades. Cole, 74 and back in her native Albuquerque since 1973, has earned a loyal following for her instruments. After an initial period of making more conventional products – “Why are we all making copies of Stradivarius, one after another?” she recalls wondering – Cole adopted a more idiosyncratic approach. She matches the timbres, and styles, her clients ask her to create.

She starts each project by asking the musicians about their needs. A first-chair violinist might want a bright sound that can cut through the orchestra, a beginning player a more forgiving instrument that can smooth out imperfections of technique. “I just made a cello for a person, and she told me, ‘I know I’m not a great player, but I just want a cello that sounds nice under my ear,’ ” Cole says. She made what she calls a “mellow cello” that won’t sound squeaky, even in the hands of a less-than-expert player. She also custom-crafts each instrument so it’s fitted to each player’s unique physical attributes, such as finger length.

Construction of a violin or viola takes about 90 hours, with another 90 for finishing work. A cello takes even more time, about 250 total hours. Cole starts by drawing the instrument’s shape on a block of wood, then carves it out with a router. Next, she uses hand tools to shape the arch of the body. Though most makers would glue blocks onto a mold that they press the sides of the instrument (or “ribs”) around – an approach that ensures uniformity from instrument to instrument – Cole works piece by piece, gluing each rib to its block. “It looks like chaos, and then gradually the chaos comes into more distinct form,” she says. “At the end, you see, ‘Oh yeah, I made a cello.’ ”

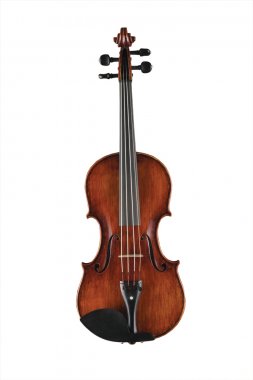

A Cole instrument is recognizable by sight and sound. She decorates the insides, visible through the f-hole (the elongated openings on either side of the strings), with floral motifs or other designs requested by customers. One asked for cranes, another a few bars of Mozart. She prefers a weathered look, wherein the varnish “wasn’t just put on like a fresh cabinet.” For tone, she uses different woods to find the right resonance. “I can come up with a huger variety of tone than [Stradivarius] could, because I’ve got all these woods,” she says, listing Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, and maple from the Pacific Northwest, among other species.

Though Cole’s experimental tendencies can result in subtle inconsistencies, she says the distinctive qualities of her instruments outweigh those seeming flaws. “Our lives are being constricted by the perfection of machines,” she says. “But the imperfection of humanity is what makes us who we are.”