By Any Other Name

By Any Other Name

Q: How is “craft” understood around the world?

A: Normally I wouldn’t presume to speak for the rest of the world. But one thing I know is that people in non-English-speaking cultures don’t really think about “craft.” Their concepts are similar, but not quite the same.

As many readers of this magazine know, our word “craft” derives from the old German Kraft, meaning “power” or “potency.” (That’s a good fact to bear in mind if someone tries to persuade you that traditional crafts are fragile.) In modern German, though, there is no precise equivalent. Handwerk might seem close, but it has a totally different connotation. A Handwerker is a manual laborer – someone who, say, pours a foundation in concrete, not someone who fashions a museum-quality object. The latter counts as Kunsthandwerk, which is like saying “art-craft,” but refers specifically to the decorative or expressive application of a trade skill.

This terminology has close relations in the Scandinavian languages (konsthantverk in Swedish, for example). That part of the world also gave us the wonderful word slöjd. While it is sometimes translated as “handicraft,” the term implies an amateur or avocational context. Thus hemslöjd means “domestic hobbies.” There was a slöjd movement in education in the years around 1900, which was designed to instill good character through workshop training.

The simplest Japanese translation for “craft” is kogei, and the language also has a parallel term to the German Kunsthandwerk: bijutsu kogei, with bijutsu meaning “fine art.” But there are also a plethora of others. Maybe a nation so saturated in craft traditions needs them, just as the Inuit supposedly have lots of terms for snow. There is mingei, meaning roughly “the crafts of the common people,” and also a historical oddity, kurafto. Though it is a direct borrowing from the English word, this term dates to the time of the American occupation after World War II and refers to a mass-produced object made to look handmade, usually for the export market.

Latin-derived languages are yet another story. They lack any direct equivalent for “craft,” but have an important concept that we lack in English: the artisanat. (That’s the French; there are similar words in Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese.) Unlike the English “craft,” l’artisanat refers to a definitive class of people, not products. The term is a bit like the British “labouring class” but refers specifically to the skilled working population. In Latinate languages something can also be artigianale, to use the Italian, which means not only that it is handmade, but also that it relates to the style and idiom of a sector within society.

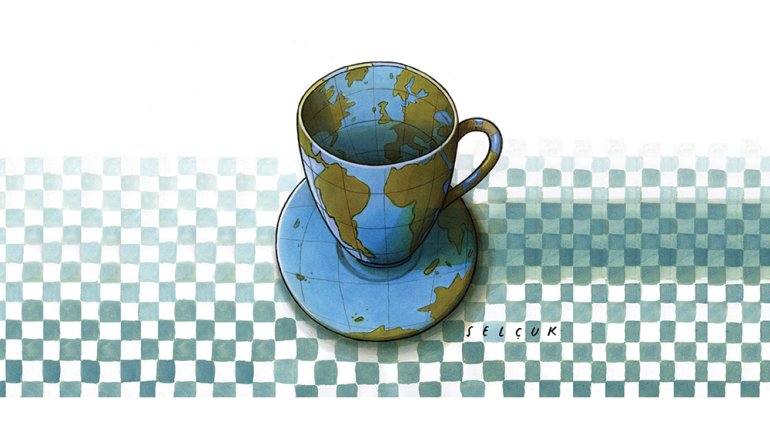

As you can see from these complex shadings of terminology, the world of making looks different depending on the words you use to describe it. This is not necessarily because the skills, materials, and processes are any different. Rather, the distinctions are social and political. I sometimes think that what we really need is a new word that encapsulates all the connotations of craft as they exist in every language. But maybe in the global world of the 21st century, it’s better to embrace a multifarious vocabulary. As in other walks of life, if we could speak one another’s language when it came to craft, we might realize the narrowness of our own perspective.

Glenn Adamson is head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and co-editor of the Journal of Modern Craft.