The Art of the Flourish

The Art of the Flourish

Fine hand engraver Jennifer Bower loves adding decorative flourishes to everyday objects and tools. She says people tend to use functional objects more often when they’re beautiful. Photo courtesy of the artist.

What we don’t know about this unparalleled craftsperson? His name. He is called the Garvan carver because his work appears in Yale’s Mabel Brady Garvan collection. “His hand was first identified in three pieces of furniture that we have,” explains John Stuart Gordon, an associate curator of American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery, who has made a career of having a discerning eye and keen appreciation for the nuances of craft. “But his furniture is in many collections. The way he carves these scrolling leaves, the way they flip over at the end, marked with rapid lines—these flourishes serve as the method of his identification.” They also secured the Garvan carver’s legacy.

This tall mahogany case clock, ca. 1765, is attributed to the Garvan carver because of its distinctive carved details. Photo by Gavin Ashworth, courtesy of the Chipstone Foundation, 1997.25.

The flourish. The extra something. The finishing touch. These gestures elevate craft from a matter of utility to an opportunity for delight and expression; from answering a need to engaging in a conversation.

For artists working today in decorative disciplines—media that are in themselves exercises in flourish, such as engraving, beadwork, and calligraphy—their craft provides opportunities for connection: to the recipient, to heritage, and to one another. And for makers carving their niche in the crowded world of craft, their flourish becomes as distinctive as a voice or a refrain of music floating above the clamor, something unmistakably their own.

Radiators & Calipers: The Hard-Working Flourish

Not all ornamentation is purely aesthetic. What may seem like a beautiful but nonessential detail can do just as much work as a chair seat or jug handle. The wagons of horse carts, for example, were carved with designs to shear off wood and lighten the load. Elaborate spirals on iron gates cover wide areas using less material. Consider even the humble radiator. When Yale planned to remove the radiators from one of its museum buildings, Gordon suggested one be accessioned as part of the collection.

“It’s so gorgeous. There are these little fins and knobs sticking off in every direction,” says Gordon, noting that the resulting increased surface area helps deliver more heat to the room. “It’s a functional object in use, and then the details make it an object of visual delight. The flourish is really working hard in something as unsexy as a radiator.”

The pleasure a meaningful detail can stir also has a function. Jennifer Bower, a Michigan-based artist specializing in fine hand engraving, understands the ways in which the personal touches of a piece can lead to increased use. Most frequently her canvases are the surfaces of tools, as she fills the shining side of a plane or the tapered curve of a caliper with swirling acanthus leaves that would have impressed the Garvan carver himself.

Jennifer Bower starts by drawing her design on an item with a Sharpie marker. “The engraving tools that I use do not merely etch the surface,” she says. “I am cutting away and removing metal, line by line.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

“I started referring to my work as ‘Unnecessary Embellishment™’ because I understand that what I do is functionally unnecessary,” Bower admits. “However, I believe that adding art to a functional item, such as a tool, can give it a new life. Suddenly a tool that was lost in a toolbox becomes a little more treasured, more often used.”

Tool engraving has become Bower’s favorite type of commission because of a tool’s capacity for storing meaning and memory: “I recently engraved two small hand planes that a father commissioned for his two young daughters. Intertwined into the ornate engraving, I engraved the girls’ initials. As I worked, I thought about these two girls: how lucky they are to have a dad who wants to teach them woodworking skills, what they would make with the planes, and if they will grow up to be craftspeople someday.”

Beads & Artifacts: Radical Reclamation

Alongside adornment and function, distinctive details make statements. They can, as Gordon points out, serve as radical reclamations of identity and connection. “So much modernist theory is a condemnation of the flourish,” he says. “Early theorists aligned superfluous decoration with the ‘primitive’ and the ‘savage,’ purposely bringing in the rhetoric and subtext of colonialism and subjugation. Embracing the flourish, then, becomes a political act.”

When artist Martha Berry of Rowlett, Texas, sought to connect with her Cherokee ancestry through beadwork, which serves as cultural and artistic embellishment on garments and other items, the only education or information she could find was on the beadwork of the Plains nations. That’s because one of the starkest American examples of rending people from their land, and from their cultural traditions, took place following passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. During the 1830s and 1840s, the US government forced the relocation of several Southeastern Woodlands nations to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi to make room for white farmers and gold prospectors. The Cherokee were removed from their homelands in a brutal march known as the Trail of Tears in 1838, during which more than 4,000 people died. Because of the devastation the Cherokees experienced, with a disproportionate impact on the elders—the knowledge-keepers of the nation’s craft—their beadwork techniques and motifs were nearly erased from the cultural record.

Bandolier bags, which are shoulder bags ornately decorated with beadwork, are made and worn by several North American nations. These three by Martha Berry are called (left to right) A Whisper from the Mounds, Double Crossed, and The Plants Became Allies. Photo by Dave Berry.

So Berry worked closely with museums and academic institutions to find the photographs and artifacts necessary to re-create post-contact, pre-removal designs, earning her the designation of Cherokee National Living Treasure in 2013. “Every design, every number of repetitions of a design, every color—everything in my work has meaning. It all relates to what it is like to be a Cherokee in the modern world,” Berry explains.

Her work restores relationships severed by a brutal and oppressive past, connecting her with her ancestors while sowing seeds for the future of the craft. “I feel very much in communication with my ancestors,” she says. “I work hard to tell their stories well, to provide a conduit for them to communicate with modern people.” Now, thanks to Berry’s commitment, several Cherokees are award-winning bead artists, and they’re teaching new generations of beaders.

“Every design, every number of repetitions of a design, every color—everything in my work has meaning.”

—Martha Berry

Pens & Inks: Scripting a More Representational World

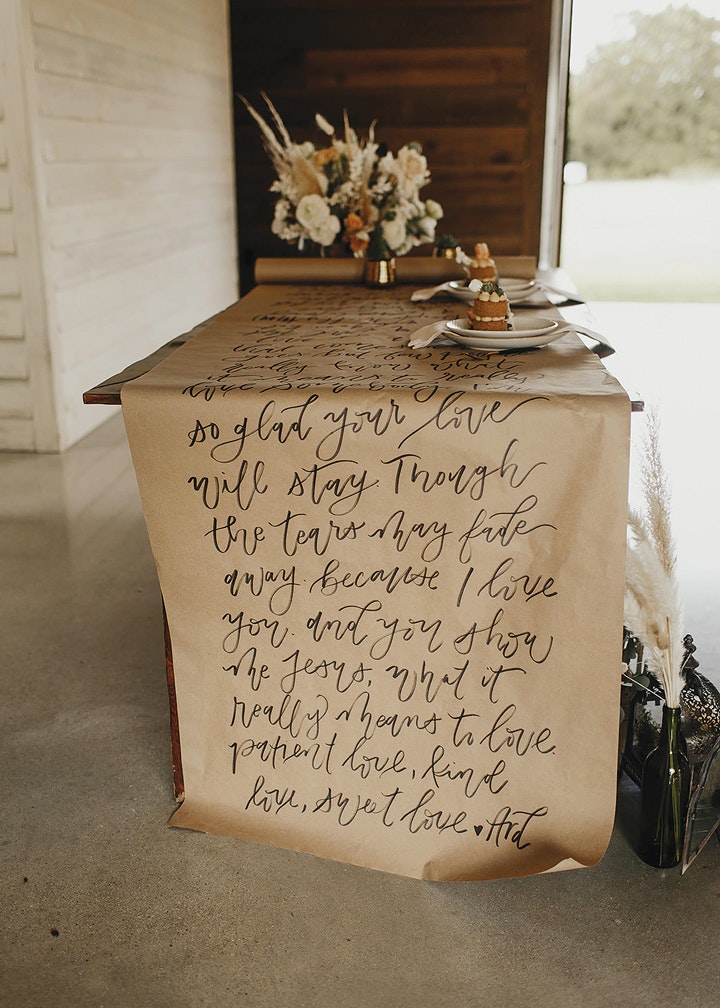

Lack of representation is another, perhaps subtler, way of distancing people from a decorative mode of expression. Amanda Reid, who lives near Austin, Texas, fell in love with calligraphy and hand lettering in 2015. Practicing calligraphy, which is often referred to as “the art of the flourish,” offered her balance from the stresses of grad school. “Calligraphy is very intentional. You have to focus on what you’re doing. It has a flow and a rhythm to it,” says Reid.

To offset the stresses of grad school, Amanda Reid took up calligraphy and hand lettering. She later founded Calligraphers of Color. Photos by Carhart Photography.

After seeking out more educational opportunities, taking workshops, and watching online tutorials, she quickly noticed an unsettling trend. “I had a hard time finding calligraphers that look like me with black or brown skin,” she recalls. “I remember standing in my kitchen one day, and I looked at my husband and said: This is ridiculous. I know I’m not the only one.”

Reid then founded Calligraphers of Color, an inclusive online community celebrating diversity in calligraphy and providing resources for calligraphers to improve their skills and share business ideas. As the community grows, it’s a testament to the way in which creating a space for many voices and many hands results in a richer experience of the craft itself.

“Bringing so many cultures together, it’s amazing to see how diverse the practice is,” says Reid. “There are people working with modern scripts, ink and nib, some with brush pens, some with watercolor, all different kinds of traditional scripts like Arabic . . . I think it’s a better representation of what our world actually looks like.”

“I had a hard time finding calligraphers that look like me, with black or brown skin.…Bringing so many cultures together, it’s amazing to see how diverse the practice is.”

—Amanda Reid

Boats Off Into the Distance: Forging Identity

If having a distinctive style once carved a space in the historic record for a craftsperson, now it forges an artist’s identity in the larger world of craft. Atlanta-based Corrina Sephora, a mixed-media artist specializing in metal sculpture, painting, and installation, embraces her signature techniques and subjects. As the granddaughter of a sea captain, nautical themes have permeated Sephora’s work. “The boat form,” she says, “became a way of anchoring my ideas, my place of departure.”

Artist Corrina Sephora credits her mentors with inspiring her to develop her own characteristic gestures. Photo by Jerry Siegel.

In her work Off Into the Distance of Still Waters, Sephora presents the repeated figure of a boat and oar, each iteration becoming smaller to create a sense of forced perspective. This echoing has become a hallmark of her work. “In blacksmithing, there’s repetition in the hammering marks, but I also work with ideas in repetition, whether that’s a series or multiple components or parts,” she says. “Repetition in the creative process allows for a rhythmic and mind-opening experience for the viewer, which is where the magic occurs.”

Corrina Sephora’s forged steel and copper sculpture Freedom of Flight (2013) features two doves soaring above a boat balanced on top of waves that curl beneath it. Photo by Phillip Breske.

Sephora credits a strong sense of identity in the works of her mentors—Elizabeth Brim’s whimsical explorations of the ferrous feminine, Nol Putnam’s sinuous refutations of gravity—with inspiring her to develop her own characteristic gestures. Flourish, it seems, can also function as an inheritance passed from teacher to student, each recipient reinscribing it with his or her own touch.

These “little” touches, the marks of the maker’s hand, may not perform a function the way a dovetail joint or a running stitch would, but they nevertheless serve a crucial purpose. If the act of making things is one of our distinguishing traits as humans, the act of making things beautiful eloquently expresses our humanity. These flourishes are voices. Some echo down the hallways of time. Others urge, gently, “Pick me up, put me to use.” Some break imposed silences to reassert their belonging. And still others are like the voice of a friend, familiar even in a crowded room.

“Repetition in the creative process allows for a rhythmic and mind-opening experience for the viewer, which is where the magic occurs.”

—Corrina Sephora

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.