Body Land Memory

Body Land Memory

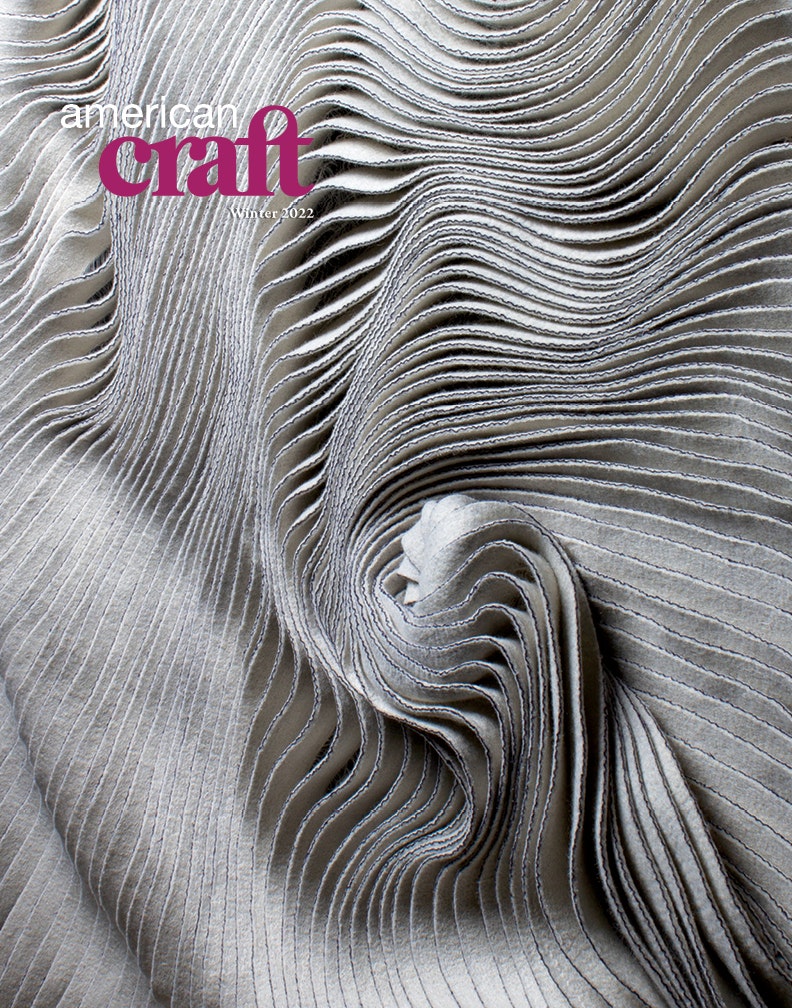

Coiled and woodfired, the True Blue Vessel II, 2021, was made from soil from the former plantation where Gbadebo’s ancestors were enslaved. The locks of human hair were dipped into slip made from the soil.

That professor couldn’t have known it, but this erasure helped set Gbadebo on a path toward an iconoclastic career, one in which she rejects traditional art tools for materials that forefront Blackness and link her to both her family’s history and the wider African diaspora.

True Blue

Gbadebo’s recent work centers on a group of former plantations in Fort Motte, South Carolina. After learning from relatives that her maternal family’s ancestors were once enslaved on the plantations, Gbadebo decided to investigate them. She discovered the plantations had once produced rice, cotton, and indigo dye; two plantations were even aptly named True Blue. One of the True Blues, on Pawleys Island, South Carolina, had since been transformed into a golf course, trading its history of forced labor for one of leisure and privilege. The other True Blue, where Gbadebo’s relatives continue to bury their dead, lay in neglect. The ties between these elements—the land, its materials, her ancestors, and the erasure of their history—seemed self-evident to Gbadebo, and ripe for artistic exploration.

“Enslavers took us from the ‘Rice Coast’ of Africa to these spaces in the Carolinas and Georgia, where we could transfer the knowledge of the land that we carried in our bodies,” explains Gbadebo. “The land and our Black bodies have always been connected, and they’re still connected.”

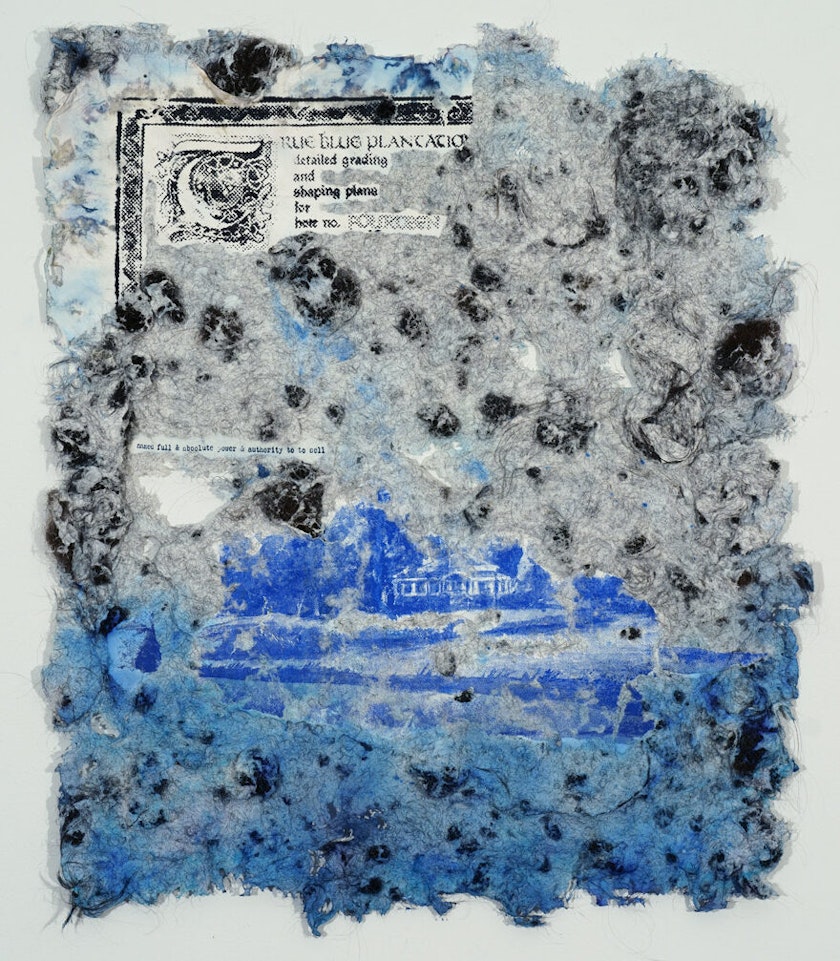

Gbadebo blended rice paper, cotton, indigo dye, water, documents, and Black hair sourced from barbershops to make “history papers” for True Blue: 18th Hole. Photo courtesy of Claire Oliver Gallery.

In her 2020 solo exhibition, A Dilemma of Inheritance, Gbadebo illuminated those connections in the form of “history papers.” Using papermaking techniques, she blends Black hair (sourced from a network of supporters and Black barbershops), rice paper, cotton, indigo dye, and water to create highly textured paper sheets in saturated shades of blue. The sheets also incorporate silk-screen prints of old photographs, architectural plans for the golf course, and details from historical records about the enslaved individuals who once worked the plantations. The finished pieces resemble abstract maps and portraiture, reclaiming and recontextualizing the land and its history.

True Blue: 18th Hole #9, 2020, incorporates architectural drawings of the True Blue Golf Club on the former True Blue Plantation on Pawleys Island, South Carolina. It is one of 18 pieces that make up the larger True Blue: 18th Hole. Photo courtesy of the Claire Oliver Gallery.

Gbadebo’s history papers also confront the color blue conceptually. “Blue’s such a beautiful color—my favorite, actually—but the history of the color blue is very violent,” she says. She notes how the demand for indigo dye drove slave trades around the world for centuries. “For me, blue became an interesting tool for playing with these dynamics of violence and beauty.”

A Simple Question

“It started off as a simple question,” Gbadebo says of the pieces in Dilemma. “Could hair become a paper document? What happens when you add hair to rice paper? And what does it mean that there’s genetic information contained in hair?” Gbadebo started thinking of turning hair into paper as creating a new kind of archive: “You’re not necessarily reading history, but the actual sheet itself is history.”

Adebunmi Gbadebo (pronounced Ah-Day-Boo-mi, Bha-Day-Bo) at work on Production I. Photo by Kelsey Jackson.

This process—of starting with a question and letting the work evolve from there—reflects Gbadebo’s deep curiosity and affinity for hypothesizing and testing. In fact, the School of Visual Arts grad was the inaugural (and for a time only) fine arts student at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. It’s telling that in addition to a studio assistant, Gbadebo recently hired a research assistant as well.

As an artist in residence at The Clay Studio in Philadelphia, Gbadebo is expanding her exploration of True Blue in yet another direction: using soil from the plantation’s cemetery as a base for ceramic sculptures. And once again, it all started with questions: Could she make a body of work from this land? How might soil be a repository for memory, and how can one activate that memory? “I’ve represented the land through historic documents and cotton and indigo,” she says. “But it wasn’t until I actually traveled to True Blue that I realized I could literally use the land in the same way I use our bodies through hair.”

TOP: Gbadebo touching the headstone of her great-great-great-great-grandfather William Ravenell at the True Blue Plantation cemetary. Photo courtesy of the artist. BOTTOM: Gbadebo created the gas-fired True Blue Vessel with soil from the cemetery using a Nigerian coil building technique. Photo by Adebunmi Gbadebo.

Where will Gbadebo’s boundless curiosity take her next? “I don’t know. Even three or four years ago, I wouldn’t have guessed I would be using any material outside of hair,” she muses. “And it’s not that hair is done speaking to me—it’s just that I’ve found other materials to support what I want to say. The practice evolved. So whatever I do next, it will have to evolve naturally from whatever I’m doing.”

One clue to Gbadebo’s future might already be present in her work: water. She mentions offhand that in addition to keeping jars of water in her bedroom (“just a few little ones”), she takes a particular bottle of water with her when she travels. “I do have some notes about our historical relationship to water as Black people,” she adds. “I call water my invisible material, because you need it to make both paper and clay.” Thankfully for art lovers, if there’s one thing Gbadebo has proven adept at, it’s taking disregarded materials and erased existences and giving them a body and voice once more.

adebunmi.carbonmade.com | @adebooms

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.

This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.