Bright Future

Bright Future

In the town of Hoi An on Vietnam’s central coast, gazing out at the Thu Bon River at night is like looking into an oil painting. The dark, glossy water ripples with reflections of colored light from glowing silk lanterns hanging nearly everywhere — from the footbridge crowded with pedestrians, the rowboats carrying chatting tourists, the façades of Chinese shophouses and the balconied French colonial buildings lining the banks.

The lanterns are the hallmark of the city of 120,000 and its exceptionally well-preserved Ancient Town. They are also a symbol of its transition over 500 years from a bustling commercial port on the South China Sea to a forgotten backwater to one of Vietnam’s top tourism destinations.

The lanterns are among traditional crafts in Hoi An, as are the long tunic and pants known as ao dai and bamboo basket boats, which once were all integral elements of daily life and culture; in recent decades, for better or worse, they have become merchandise for the booming tourism trade.

“If you think about it, Hoi An relies on tourism to live,” says Patricia Clegg, a consultant for Yaly Couture, one of the city’s pioneering tailors. “Before, a lot of people had to leave Hoi An to work in Ho Chi Minh [City] or wherever. Now they stay here because there’s opportunity.”

Quynh Trinh, who founded Yaly, embodies that potential. She was born in the early 1970s and grew up as the country was still suffering from the ravages of war. In the 1980s, she learned how to make the ao dai from the fabric sellers in the local market.

That was around the same time that preservationists started helping restore the city’s unique fusion of Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, and European architectural styles; this was after two centuries of neglect, as Da Nang, about 20 miles north, overtook Hoi An as the major regional port.

Their efforts resulted in UNESCO World Heritage site status in 1999 for Ancient Town, which features ornate pagodas, temples, and meeting halls.

Quynh had opened her first tailor shop four years earlier, making white ao dai mainly for staff in the few restaurants in town. But as increasing numbers of foreigners arrived, wanting to buy traditional clothing, she started to innovate, designing the ao dai in different colors and patterns.

She also learned how to make men’s suits, Western wedding dresses, and all sorts of shirts, pants, and dresses that tourists brought in to be duplicated. “I thought, ‘Why do only the souvenir garment?’ ” Quynh says. She now has 380 tailors and three shop locations, including one large enough for tour groups from the cruise ships that dock in Da Nang.

For centuries, inhabitants relied on fishing as their livelihood, and one of the most astonishing watercraft is the round bamboo basket boat. Fishermen still launch them from the city’s beaches, but the boats are most prevalent on tributaries of the Thu Bon River, where fleets of them float through water-coconut groves, the boatmen singing and rocking to music as tourists shriek in delight.

While few make the boats by hand anymore, on Cam Kim Island south of town, you can still find 85-year-old Do Sung squatting in his workshop, a cigarette dangling from his mouth as he hammers and weaves. It takes him a month to make a 4- to 6-foot-diameter boat, cutting long strips of bamboo, interlacing them on the floor, then waterproofing the basket with tree resin and water buffalo dung. He will offer you a chair with a smile so you can watch him work.

A stroll through the streets of the town at night can be magical if it’s not a weekend or a holiday, when the crush of tourists is almost overwhelming. The wow factor comes from the glowing lanterns, and Huynh Van Ba, 75, is the pioneer of their proliferation.

Before Vietnam opened to tourism, lanterns were mostly red and white paper globes confined to the Chinese pagodas and temples. When the travelers arrived, they wanted to buy them.

“Foreigners were adoring them, but there was only one problem,” Huynh remembers: The lanterns proved too fragile to transport. So in the 1990s, government officials asked Huynh, then making lanterns for the pagodas, to come up with a solution.

He designed a mechanism to allow the globe-like shape to elongate into a tube that’s easy to tote. Over the years, he added a variety of colors and prints, and started making them in various shapes like teardrops and garlic bulbs. By the mid-2000s, dozens of shops around Hoi An were making the lanterns by hand, with a number of the artisans trained by Huynh.

His staff of 15, mostly family members, makes about 200 lanterns a day on the ground floor of a narrow building, with an open room divided into a jumble of work piles. The 10-step process includes cutting thin strips of bamboo for ribs, fastening their ends to wooden rings, gluing silk swaths to the bowed slats, and stringing together tassels that sway in the breeze.

Several years ago, the lanterns were shown mostly during the monthly full moon festival, when businesses’ exterior lights were dimmed. But with the visitors and lanterns multiplying, now, most every night is a mesmerizing festival of lights.

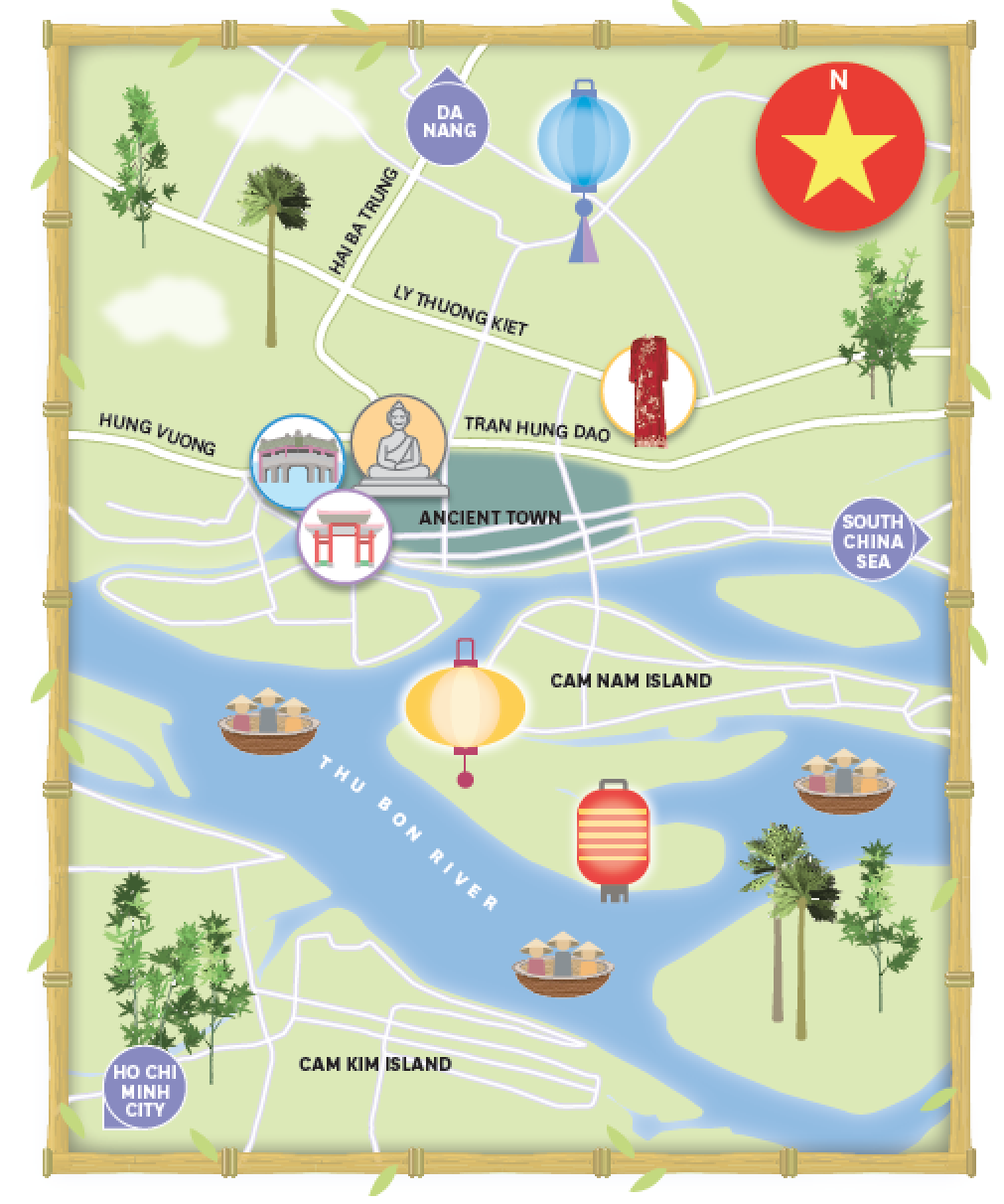

Map by Michael Kline

Ancient Town

Visit Reaching Out Arts & Crafts, which employs people with disabilities, and watch artisans tapping brass rims onto ceramic cups and embroidering napkins. In the showroom, you can browse beautifully designed ceramic cups, teapots, and place settings, including a bowl with a small hole on the side for resting chopsticks across the top. The social enterprise offers workshops on craft making and meditating over tea. It also runs the nearby Reaching Out Teahouse.

Hoi An has an astounding 600 tailor shops, and you can’t go wrong having an outfit made at Yaly Couture. You can also watch workers make traditional ao dai at the Yaly boutique. Check out the town’s signature lanterns at Huynh Van Ba’s lantern-making shop, and take a class to make your own lantern. You can also admire art photography and traditional costumes at the Precious Heritage Museum in the French Quarter on the eastern edge of Ancient Town.

Kim Bong Carpentry Village

Located about two miles south of Ancient Town over the bridge on Cam Kim Island, the village is home to craftspeople renowned for their boats, furniture, and intricate carvings for pagodas in Hoi An and the former imperial city of Hue. Huynh Suong, a 14th-generation woodworker, helps run the family’s Huynh Ri carpentry workshop, where you can marvel at the bamboo bird cages he has built into the twisting roots of teak and mahogany trees.

If he’s not busy, Suong will give you a ride on his motorbike to see Do Sung, one the few artisans still making Hoi An’s bamboo basket boats. The workshop is at his house; there is no address, but find Cafe 78 - Co Lieu on Google maps, and it’s just a few houses east. You can also see the boats in action on the picturesque Hidden Beach several miles northeast on the seaside, where fishermen paddle out to sea just before sunset.

Hoi An Impression Theme Park

To experience the city via a musical extravaganza, hike over a footbridge to Hoi An Impression Theme Park in the middle of the river, with a 3,300-seat amphitheater overlooking a replica of the Ancient Town waterfront. A cast of about 500, including scores in ao dai and illuminated conical hats, tells the story of the port’s evolution each night.